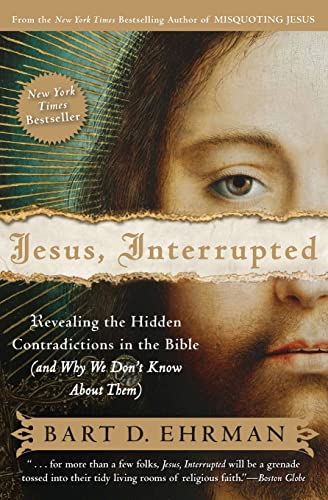

Jesus, Interrupted: Revealing the Hidden Contradictions in the Bible (And Why We Don’t Know About Them)

Written by Bart Ehrman Reviewed By Darrell L. BockBart Ehrman’s Jesus, Interrupted by his own admission says nothing new. It packages what scholars have been saying about issues in the Bible in a very public way for two decades. As Ehrman points out, these issues go back centuries—and the positions he defends have been advocated for a few centuries. What the book does is put many of these well known examples in one place, laid out so anyone reading the Bible has to face up to them. In a real sense, Jesus, Interrupted is an “in your face” book for those who have a high regard for the Bible. Saying in effect, “Take that,” Ehrman tackles an array of textual issues. His chapters discuss supposed contradictions he sees in the text, the point of variant readings, debates about authorship, treatment of issues tied to the historical Jesus, and discussion about orthodox Christianity emerging later than the first century out of an originally more diverse situation.

In fact, folks like Augustine and Origen were aware of the kinds of issues he raises. Answers and debates around what Ehrman raises have been around for a long time, but one reading this book would never really know what the real conversation is about in these kinds of examples. Ehrman begins his study on a biographical note. He often does this in his books to tell how, becoming enlightened, his position changed. He notes that when he learned the historical critical method in place of the devotional method, he discovered the Bible was full of contradictions and discrepancies. He came to see it as a completely human book with Christianity being a religion that is completely human in its origin and development. His experience portrays the core thesis of Jesus, Interrupted. Ehrman has become a one-man band seeking to make clear what everyone should know about the origins of the Christian faith—its roots can be explained on completely human terms.

However, one can say Ehrman rigs the rules to get here. We cannot speak of the divine in any of this, he says, because historians cannot handle that kind of data. This represents a convenient limitation on what he can speak about (even as he makes all kinds of pronouncements about what is taking place and who is responsible). This book is valuable not for the points it makes, but for what it represents, a statement by a noted university professor who effectively communicates his understanding for how Christianity should be seen. Ehrman is an excellent example of how Christianity is being presented in the public square to many today. His works regularly make the New York Times best-seller list and receive prominent attention in popular bookstore chains.

One has to wonder what the motive is for writing a book when an author admits to providing nothing new in it. He claims he seeks to inform. One of the things Ehrman does effectively is communicate the tensions he sees. This book is really about packaging. What has made Ehrman somewhat of a phenomenon is that he writes clearly and makes complex issues of biblical study accessible to so many (although it is very much with his twist on things). However, to leave the assessment with this point would be to ignore the case Ehrman tries to make. Let’s look a little deeper at how this presentation works.

Ehrman wishes to challenge the conservative writers and the perspective they represent. These writers actually have engaged all the “non-new” points Ehrman makes, even highlighting themselves the “human” side of the Bible’s production. However, reading Ehrman one would never know that. Ehrman works partly by caricature, partly by selectivity, and partly by setting rules where God cannot be invoked in a historical discussion. God cannot even be brought into the possibility of consideration in an interpretive spiral because “miracles are not impossible,” just very much unlikely and a least likely explanation (read a “next to impossible,” so virtually unusable, category).

I think what is most bothersome in this book is the way it sets up discussions. It pursues a topic for several pages, often noting in one or two quick and embedded sentences that the point is not as devastating as the impression given by the rhetoric of the whole section. Such qualification involves a quick almost aside that qualifies things so the author has cover. But it becomes a faint cry in light of the more skeptical thrust of the whole work. The result is to launch a discussion in a direction that implies more than the evidence really gives, leaving a greater impression about what is said than the author claims in the qualification. More than that, by excluding other key factors, the discussion leaves the impression of making a point clear that actually is not as cut and dried as the presentation suggests.

It would take a book to go through the many, familiar examples Ehrman raises—and that could be done. There are responses, scholarly credible ones, to virtually all the examples he raises. Let me take on one in detail that also was highlighted in his promotional video on Amazon.com. My point is to suggest that things are not always what they seem when they are set forth in Jesus, Interrupted.

In the video Ehrman claims (and then writes in the book) that Jesus dies in despair in Mark but as one in control in Luke. He argues these are diverse and contradictory portrayals. The key, he argues, is to appreciate the difference between Mark citing Ps 22:1 and Luke’s appeal to Ps 31:5. Now here is what Ehrman does not indicate to readers or does not develop for his readers in terms of applying the significance of key facts to this example. Fact 1: Most scholars agree that Luke used Mark. Both Ehrman and I agree with this point about Luke’s use of Mark. But he does not apply this fact to this example. I will show why it is important below. Fact 2: Mark speaks of a second cry from the cross in his account. Fact 3: Jesus in Mark (and in the Mark that Luke works with) has been predicting his death and choosing to face his death long before depicting the pain of the cross. Fact 4: Jesus supplies the very testimony against himself at the Jewish trial scene that leads into his crucifixion in Mark 14:62, hardly the act of a completely despairing man. I make this last point because Ehrman wants to preclude a citation of Ps 22:1 being uttered to point to the entire lament that is Ps 22, including the resolution of vv. 19–31. This example of reading (almost in the very flat, excessively literal fundamentalistic straw-man manner he wants to criticize) happens throughout the book. This is just an especially good example of it. In the midst of discussing Luke, he claims Jesus has no substitution of sin in his theology, ignoring the explicit statement in Acts 20:28 (remember we are discussing Luke’s theology here as the basis for his changes). Another feature of Ehrman’s approach is that he consistently appeals to what are possible readings of texts in combination while chiding those who combine things differently and more harmoniously. Remember we are speaking of writers who respected each other enough to be using their material.

What I would claim from this example is (1) Luke does highlight Jesus’ control of the situation to a degree Mark does not (so Ehrman and I would agree here that this is true). However, conservatives have affirmed the different emphases between Gospel writers for years (I even wrote a book working through these kind of examples in the Gospel tradition called Jesus according to Scripture), and numerous commentaries by scholars (not all conservative) could see such differences without going on to create the theological distance Ehrman does between Mark and Luke. (2) Luke, knowing of the second cry in Mark, supplies what else Jesus said in a process not unlike the way in which a lawyer or an investigator might follow up on such a detail. Now we could discuss and debate whether Luke made this second saying up (as I suspect Ehrman might argue) or whether he had access to sources (as I am inclined to think), but my point is that one can easily read Luke as supplementing Mark here, not completely rejecting Mark’s portrait of Jesus. Luke could do so while omitting reference to Ps 22:1 because its content was already known from Mark. It is important to note that Luke’s locale of this Ps 31:5 utterance comes at the spot where the second cry comes in Mark. (3) Thus, the theologies of the cross are not in as great an opposition to each other as Ehrman claims. Rather what we have are emphases. In Mark, Jesus goes triumphantly to his death genuinely fully suffering, with the second evangelist presenting Jesus as an example, even to the point of despairing yet turning in the end to God. (If Jesus is as despairing as Ehrman suggests, then Jesus ceases to be the example Mark sets forth.) Luke shows a Jesus also in control, something the other passages in Mark also indicate.

In sum, this book is significant because of the kind of statement it represents, not for the way it makes its case. It also reflects a challenge to those who think differently about Scripture than Ehrman does. More of us need to be writing to this kind of an audience with a style that makes accessible to a lay person the resolution of the kinds of issues Ehrman raises. Jesus does not need interrupting; he needs to be understood.

Darrell L. Bock

Darrell L. Bock

Dallas Theological Seminary

Dallas, Texas, USA

Other Articles in this Issue

We want to understand how the power of God comes into our preaching...

Martin Luther was a pastor-theologian. He worked out his theology in the midst of teaching, preaching, participating in public controversy, and meeting all kinds of pastoral needs...

Bearing Sword in the State, Turning Cheek in the Church: A Reformed Two-Kingdoms Interpretation of Matthew 5:38–42

by David VanDrunenAmong the many biblical passages that provoke controversial questions about Christian non-violence and cooperation with the sword-bearing state, perhaps none presses the issue as sharply as Matt 5:38–42...

Does “Christocentrism” betray an asymmetrical trinitarianism that neglects the Father and the Spirit? The spate of calls for “Christ-centeredness” in evangelicalism’s past few generations collude with the twentieth century’s revivified trinitarianism to prompt this question...

feel honored to be able to give this lecture named after John Wenham...