One would expect Andrew Peterson to be more at ease roaming the streets of Oxford and dining at The Eagle and Child pub with the Inklings of a half-century ago than in the contemporary music scene of his native Nashville.

At his core, Peterson is a storyteller. He’s a singer and songwriter who views his music as a way to connect individual stories with God’s great story of redemption. Perhaps his most popular album, Behold the Lamb of God, attracts people each year at Christmas as Peterson and his band of friends tell “the true tall tale of the coming of Christ.”

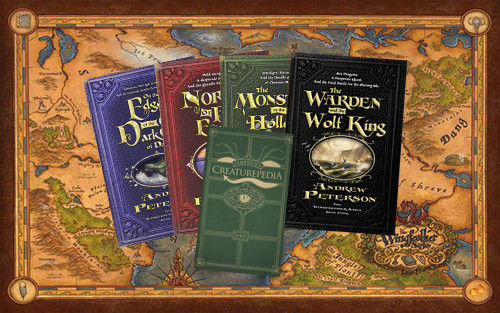

Most recently, Peterson has dabbled in children’s fantasy novels, last year finishing the much-anticipated final volume in his Wingfeather Saga. (Andy Naselli draws attention to the series’ compelling storyline, edifying themes, and entertaining style.)

Like the Inklings of yesteryear, Peterson understands the importance of coming together with kindred spirits (even if not in an English pub). Almost a decade ago he and some friends began The Rabbit Room for such people. “The Rabbit Room is a place for stories,” he then wrote. “For artists who believe in the power of old tales, tales as old as the earth itself, who find hope in them and beauty in the shadows and in the light and in the source of the light.” And for half of that time this digital community has met for the annual Hutchmoot retreat, a “gathering in celebration of books, music, and works of art that tell the truth beautifully.”

This Friday (October 9) marks the release of Peterson’s newest album, The Burning Edge of Dawn. I corresponded with him about the different approach he took with this album, what he’s learned about God and himself through (in what he describes as) a “long, painful night,” how writing fantasy novels has affected him, and more.

Unlike your previous albums where you stitched together songs you’d been working on for some time, these songs were essentially written and recorded at the same time. With this limited window you decided to “write about exactly what’s happening in my life right now, in real time.” What was that process like?

It was scary. A lot of people thrive on that sort of pressure, but I thought it was going to smash me flat. I remember telling a few friends I was headed into the studio with basically no songs, and I truly couldn’t imagine how it was ever going to work. It was impossible to picture the finished product.

Usually I start a record with a handful of songs, enough to have a map to follow. This time there was no map. Only my producer, Gabe Scott, telling me it was going to be all right.

In “The Dark Before the Dawn” you sing,

I’ve been waiting for the sun

To come blazing out of the night like a bullet from a gun

Till every shadow is scattered, every dragon’s on the run

Oh, I believe, I believe that the light is gonna come.

What did you learn about the Lord and yourself in what you’ve described as a “long, painful night”?

Just the other day I was talking with a friend about some painful stuff that happened about 15 years ago. She said, “Knowing what you know now, if you could go back and relive that season, what would you change?”

I thought about it for a second and knew I would live out of forgiveness and not anger. I would recognize how small some giant things actually turn out to be.

She said, “Okay, now look at your situation now. Imagine living out of your future self. Imagine what the future Andrew would tell you about where you are and what God is doing.”

It was a helpful exercise. Who do I want to be? I want to be the kind of person who has a ruthless trust in his King. I can imagine my future self telling me to be patient that God who began a good work in me will bring it to completion. Sometimes writing these songs gives me a picture of what the Lord is up to even when I can’t feel it.

To answer the question simply: patience. I’ve learned that it takes time and work for good things to grow. And if God says he’s growing something new and beautiful, it’s not a matter of if—but a matter of when.

Marriage, to quote another of your songs, is like “dancing in the minefields,” fraught with peril. You echo some of these themes again in “I Want To Say I’m Sorry” and “We Will Survive,” reminding us marriage requires sanctified work, continual forgiveness, and a persevering gaze toward our future with Christ. But you’re not glum. You see marriage as a gift and in “My One Safe Place” you write about it being a peaceful oasis amid life’s storms.

What has been the most surprising or important thing you’ve learned about marriage?

Jamie’s love for me has been, without a doubt, the clearest picture of God’s affection in my life. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve wondered what she sees in me. But every single morning I wake and walk into the kitchen (she’s always the first one up), and she hugs me. Every single morning, God’s mercies are new.

Marriage, I’m sure, teaches different people different things, but for me it’s been 20 years of God whittling away my assumption that he’ll just get sick of me one day and change his mind. Like I say in “One Safe Place,” that’s a weight Jamie wasn’t meant to carry—even so, she’s a window into God’s great affection for me. It’s changed me.

You end the album with “The Sower’s Song,” asking the Lord to “abide in me.” What does it mean to invite God to abide in us? And what difference does this make when going through the rough and dark moments of life?

If you read that passage in John 15 where Jesus tells his followers to abide in him as he abides in us, he also says, “I am the vine and you are the branches.” He talks about how God removes the vines that don’t bear fruit, and that no vine bears fruit without him.

Sometime during the making of this album I was literally pruning my grape vines. I looked it up online and learned exactly how to do it, partly because I forget every year, and partly because real pruning just seems too violent to actually be helpful. I was out there lopping away at these vines that I planted years ago and thinking, I hope I’m not screwing this up. I really want grapes this year. It was a troubling process.

Then, in the middle of this dark season, I read that verse in John and was reminded that bearing fruit comes at a cost. In fact, if I’m growing in Christ, I should expect to be pruned.

This song is me trying to muster the courage to ask for the pruning, in the firm belief that if Jesus says this is how it works, then it’s foolishness to resist.

What song stands out in your memory when you look back at your career?

You might be asking about my own songs, but what comes to mind is “The Love of God” by Rich Mullins. The last verse is magnificent:

Joy and sorrow are this ocean,

And in their every ebb and flow,

Now the Lord a door has opened

That all hell could never close.

Here I’m tested and made worthy,

Tossed about and lifted up

In the reckless, raging fury

That they call the love of God.

That says more about the theme of my new record than I could say in ten songs.

Many know you not only as a musician but also as writer of the Wingfeather Saga. After the long-awaited release of the fourth and final book last year (The Warden and the Wolf King), what is it like looking back at the story you told and the world (“Aerwiar”) you created? And are you thinking at this point of writing more books?

Writing the Wingfeather Saga is one of the sweetest things about my life. I had no idea when it started how much I’d learn about God, the depth of connection I’d feel with my readers, or the sense of bittersweet satisfaction I’d feel when it was finished.

It scratched the same creative itch I get with music, with the huge difference that writing books allows me to stay at home with my family and community, while music tends to pull me away.

And yes, I’m planning to write more books. I can’t wait to get started.

Download your free Christmas playlist by TGC editor Brett McCracken!

It’s that time of year, when the world falls in love—with Christmas music! If you’re ready to immerse yourself in the sounds of the season, we’ve got a brand-new playlist for you. The Gospel Coalition’s free 2025 Christmas playlist is full of joyful, festive, and nostalgic songs to help you celebrate the sweetness of this sacred season.

It’s that time of year, when the world falls in love—with Christmas music! If you’re ready to immerse yourself in the sounds of the season, we’ve got a brand-new playlist for you. The Gospel Coalition’s free 2025 Christmas playlist is full of joyful, festive, and nostalgic songs to help you celebrate the sweetness of this sacred season.

The 75 songs on this playlist are all recordings from at least 20 years ago—most of them from further back in the 1950s and 1960s. Each song has been thoughtfully selected by TGC Arts & Culture Editor Brett McCracken to cultivate a fun but meaningful mix of vintage Christmas vibes.

To start listening to this free resource, simply click below to receive your link to the private playlist on Spotify or Apple Music.