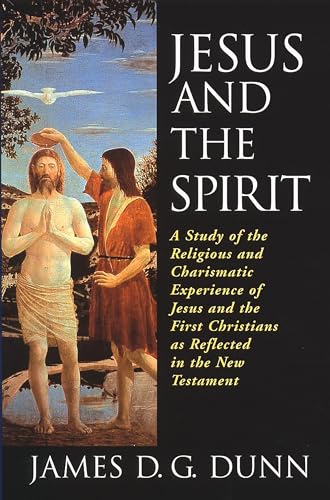

Jesus and the Spirit: A Study of the Religious and Charismatic Experience of Jesus and the First Christians as Reflected in the New Testament

Written by James D. G. Dunn Reviewed By Max TurnerDunn’s earlier book on Baptism in the Holy Spirit (London: SCM, 1970) closed with the promise of a future study of the experience of the Spirit in the early church. Now, five years later, his promise has been abundantly fulfilled. As the subtitle suggests, he has broadened the scope of his enquiry and presents us with a full-scale, massively documented discussion of the religious experience of Jesus, of the earliest Christian communities and of Paul and the Pauline churches. Few modern books show quite the breadth of reading (about 600 authors cited) and patient care in argument that Dunn offers and fewer still manage to combine these features with the production of a book which makes compelling and stimulating reading in an area of such crucial importance to the Christian.

The first part of Dunn’s book is an attempt to construct a picture of Jesus’ experience of God. His analysis is conducted in full knowledge of the jungle of critical problems involved and yet he persues it with admirable sure-footedness and a close affinity to the approach of Joachim Jeremias’ New Testament Theology. He breaks into the circle of problems with the observation that Jesus, like other men, prays to God and it is from this element of Jesus’ life that he begins to build. Can we perhaps ‘listen in’ to Jesus’ prayers and deduce some of the elements of his experience? Dunn is sure that once we clear away the cobwebs of redactional activity spun by the early community and the evangelists, we can arrive at a relatively dependable core of tradition in which the reflex of Jesus’ experience of God is expressed in the prayer ‘Abba’. This address points to Jesus’ understanding of his sonship as in some sense unique (for when the disciples are taught so to pray, their ‘Abba’ derives from their relationship to Jesus) though we cannot speak yet of a consciousness of divinesonship.

Dunn then turns to the question of Jesus’ experience of the Spirit, ignored by liberal protestantism. The relevant authentic logia (Mt. 12:28; Mk. 3:28 and parallels; the Q sayings embedded in Lk. 6:20b and 7:18–23) point to Jesus’ understanding of himself in terms of Isaiah 61:1–2. Jesus thought of himself as anointed by the eschatological Spirit because in his ministry he experienced a power to heal which he could only understand as the power of the end-time and an inspiration which he could only understand as the gospel of the end-time (p. 67). If Jesus was a ‘charismatic’ figure he was strikingly different from other such figures. The distinctiveness does not lie in the kind of works that he performed (e.g. the nature miracles—about which Dunn is extremely sceptical) but in (a) the quite unmagical quality of Jesus’ works which (b) require a demand for a response of faith (albeit not yet in Jesus, but in the Spirit of the kingdom at work through him) and (c) highlight the charismatic nature of Jesus’ authority. Jesus does not speak of his own faith, nor does he regard his authority as derived (compare the ‘Thus says the Lord …’ of the prophets with Jesus’ ‘Amen, I say.…’). These are further pointers to his distinctive self-understanding, which cannot be explained by describing him either as ecstatic or mad.

No idle curiosity prompted Dunn’s painstaking search for clues to Jesus’ experience: it has a point. In so far as Jesus’ experience is common to the disciples (even if theirs is derived) he becomes archetypal and the gulf between the religion of Jesus and that of Paul is narrowed to within tolerable limits. At the same time the distinctive element in Jesus’ experience of God provides, for Dunn, the bridge between Christologies ‘from below’ and those ‘from above’. ‘It is this transcendent otherness of Jesus’ experience of God which roots the claims of Christology in history’ (p. 92).

The second part of Dunn’s book turns to the question of the religious experience of the earliest community. Was Jesus simply the first Christian or was the experience of the church qualitatively different? The midwife that brought the church to birth was religious experience: experience of the risen Jesus and of the Spirit. The neat distinction between these two, Dunn says, is due to Luke. For Paul the risen Christ is the life-giving Spirit and so the whole issue is more complex. Nevertheless Dunn thinks that a thorough examination can show that (a) Paul did distinguish the appearance of Jesus which sealed his apostleship from subsequent experiences of Christ. (b) He regarded it as the last of a number of similar experiences (by other apostles) of a unique kind (p. 103). (c) Common to all of these is the fact that the Jesus who appeared was himself the good news to be proclaimed. (d) Luke’s portrait of a new dynamic experience of the Spirit (not exactly a resurrection experience (pace Dobschütz) yet not as sharply different from them as Luke would have) at Pentecost is probably accurate, as is his description of the early community as ‘enthusiastic’ and charismatic in every aspect of its common life and worship, its development and mission. (e) The experience was centred on Jesus and this marks the distinction between Jesus’ experience of the Spirit and that in the early community. (f) Luke is only to be censured for (i) covering over the eschatologically based nature of the early enthusiasm; (ii) failing to record the early community’s understanding of the corporate significance of Jesus and the redemptive significance of his death; (iii) his undiscerning treatment of the miraculous and his crude pneumatology which is unrelated to sonship.

The third part of Dunn’s work—and the longest—examines the religious experience of the Pauline churches and of Paul himself. It is with Paul that Dunn feels the closest affinity and the result is a most sympathetic exposition of the apostle’s thought. He opens with a consideration of Paul’s understanding of grace and then takes up F. Grau’s thesis that the charismata are grace in action. A charisma is an event: an experience of grace given, neither a talent nor a possession. ‘Charisma is not a possession or an office; it is a particular manifestation of grace; the exercise of a spiritual gift is itself the charisma’ (p. 254). I must not speak of my charisma except in the sense that God may choose to act through me for others.

This view of the Spirit’s activity lies at the heart of Dunn’s understanding of Paul. His communities were charismatic through and through: the Spirit was a shared and vital experience. It is the Spirit who creates community in the first place and so it is the Spirit experienced as charismata who sustains the community and creates conditions in which Paul naturally responds with metaphors like ‘the body of Christ’, ‘sharing in the Spirit’, etc.

If the charismata became a threat to the community that was because individuals who exercised them exchanged the true goal of the gifts for lesser and self-orientated ends. The community faced with this threat is reminded of its own authority to deal with the issue and the criteria by which it must judge charismatic contributions, viz. (a) the test of conformity to the kerygmatic tradition (b) the test of love and (c) the test of oikodomē (building up). At no point does Paul command assent on the basis of his calling as an apostle of Christ. The function of such apostles is not to lay down the law. They may only appeal to the community to recognize the measure (if any) of their charisma as they speak. Paul is an apostle in a second sense (that he founded the community) at Corinth and within this sphere of apostleship (and almost against his own will) he can bring himself to make stronger demands when the situation absolutely requires it. But on the whole the Spirit provides ministries in the church: he does not guarantee offices. Authority is conceived in dynamic terms, not in a fixed form.

While charismata are ambiguous experiences in themselves, the Spirit’s manifestations are not arbitrary. The Spirit who gives the charismata is the eschatological Spirit and our experience of him now is a foretaste of the End and of resurrection existence as the community of God in Christ Jesus. We already experience the Spirit as the one who will perfect us as sōmata pneumatica (‘spiritual bodies’) in resurrection and new creation, but our present experience is simultaneously one of the weaknesses of this creation-order in which we are but ‘flesh’. Our experience of the Spirit is one of the presence of Christ in our midst and of a power at work in us conforming us to Jesus. The slow process of death and suffering at work in us is necessary, since life now must be life in this body, and the Spirit can only be present as paradox and conflict.

Dunn’s book closes with a brief glance across second generation Christianity (i.e. the Pastorals!) in which he sees the fading of the Pauline vision and the replacement of the charismatic community by an organized church centred on rigidly structured ‘offices’ to which charisma is now subordinated.

Much of this book commands assent though there are details on every page with which the reviewer would disagree and some major issues on which he is not convinced.

(1) Granted that there are very valuable aspects of Dunn’s discussion of Jesus’ experience, he appears to confuse several issues. (a) It may be true that the only access that the sceptical historian has to Jesus’ self-consciousness is through what is revealed in his prayer and in a handful of his acts and teachings. This does not mean that they were the basis of Jesus’ belief about himself (as Dunn assumes), nor that Jesus’ self-consciousness was inchoate. Historical study may deduce from Jesus’ use of ‘Abba’ that he considered himself to be ‘the son’, but we are not in a position to say that Jesus deduced his ‘sonship’ from his prayer experience of God as ‘Abba’! (b) Dunn builds no bridge between the sort of ‘sonship’ expressed in the ‘Abba’ prayer and the Messianic and Spirit-anointed ‘sonship’ discussed later. (c) He creates a false antithesis when he paraphrases Jesus’ understanding of the issues as not ‘where I am, there is the Kingdom of God’ but ‘where the Spirit is, there is the Kingdom’ (p. 49). Dunn’s position and the reply to it would demand a full article, but in brief the difficulty may be posed as follows. The synoptic tradition is notoriously devoid of logia about the Spirit. This is hard enough to explain in view of the intense interest in the Spirit in the post-resurrection community. It would manifestly be much more difficult to explain the lack of such sayings if Jesus had placed any emphasis on the role of the Spirit in his own ministry. As it is, the oldest traditions are so unanimously and unabashedly Christocentric that there is no room for priority of the Spirit. (d) It is difficult to see how Jesus’ relationship to the Spirit is archetypal. There is hardly any point of contact between Paul’s exposition of the significance of the Spirit for the Christian and Jesus’ understanding of the Spirit in his own ministry beyond the fact that both are (broadly speaking) ‘eschatological’. Jesus understands the Spirit with him as the presence of a power to redeem others; for Paul, the Spirit is with us primarily to redeem us (albeit often mutually and in a corporate context). (e) The points made above throw doubt over the rather low Christology advanced on p. 92. (f) I remain totally unconvinced that Jesus (or for that matter Paul) held the end to be chronologically close (as Dunn often asserts). To be sure, the distinctively Christian message is that the end-time order has broken in (with Jesus and with our Christian experience as a foretaste of, and manifestation of, the end), but at no point does that chronologically delimit the final events.

(2) Many of the difficulties that Dunn grapples with in part 2 of his book are based on his exegesis of 1 Corinthians 15:45 where he identifies Christ with the life-giving Spirit. This is a misunderstanding: for details see Vox Evangelica IX, pp. 61–63. So, too, is his criticism of Luke which at several points fails to discern Luke’s redactional aims. In this part he also raises the question of the creative activity of Christian prophets. In his view, prophets in the church not only modified the sayings of Jesus but also added to the tradition words of the risen Christ. Again this is a widely debated issue, on which Dunn himself promises further study, but at the present state of the discussion the reviewer is inclined to think that the burden of proof lies with those who assume this sort of activity, and who think that the synoptic tradition has to be handled with such scepticism. In view of the comments on p. 174 in this connection, it should be pointed out that the use of the OT by the NT is not a guide as to how the prophets might have handled the Jesus traditions. While the OT was often considered to point forward, as a whole, to the Christ event, and was therefore peshered, we have no evidence that the Jesus traditions could have been viewed in the same way. They were the revelation itself, not a ‘mystery’ to be revealed in the future.

(3) Dunn’s definition of ‘charisma’ is correct, but Paul’s application of the word is much wider than Dunn allows. The charisma of continence in 1 Corinthians 7 is more than the grace on one occasion to say ‘no’ to sexual desire. It is a lasting ‘gift’. This use of ‘charisma’ should not surprise us, for the word itself tells us nothing about the character of the gift other than that it is viewed as grace in action. Once this is understood there is no reason why Paul should not use the word charisma to apply both to the single act of (say) prophecy and to the calling and continual use of one man as a prophet. This in turn means that the gulf between the undisputed Paulines and the Pastoral Epistles may be much narrower than Dunn suggests. It could be narrowed even further by avoiding the temptation to build a Pauline doctrine of ministry primarily on the foundation of 1 Corinthians where the situation demands Paul’s pastoral emphasis that everyone has some‘ministry’ given by the Spirit.

There is much more that could be said but a review cannot possibly do justice to the many facets of Dunn’s case. We particularly welcome his stress on the experiental nature of the early community’s faith: here is a challenge indeed to the ‘take it by faith’ mysticism that has deadened so much of the evangelical church today. This is a book of singular importance and anyone who speaks on the subject of the Spirit or of the religious experience of the early church, without reading it, is guilty of unpardonable negligence.

Max Turner

London Bible College