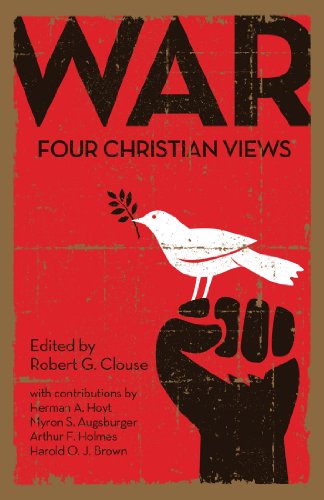

War: Four Christian Views

Written by Robert G. Clouse Reviewed By Charles E. MooreWar is one of the evil necessities which arises from the fallen state of humanity. War is evil! As Samuel Shoemaker said, ‘you do not wait for a war to look at the problem of evil, war is simply the problem of evil writ large’. It is a true saying that ‘sweet is war to him who knows it not’. There is really no question concerning the ugliness of war. As one person put it, ‘there are many evils worse than war, and war brings everyone of them’. The common consensus overwhelmingly supports the cause of peace. The teachings of Jesus advocate peace and the peoples of the earth yearn for it. But, as with so much of life, there is a strange contradictoriness as to the nature of war and the attainment of peace. No-one desires war and yet war seems to be an inevitable expression of human relations. Man in general, and the Christian specifically, is thus confronted with the inherent tensions and moral ambiguities of war. For on the one hand, war is evil. But on the other, war, or at least some wars, can produce some degree of good by establishing peace, maintaining justice and protecting the lives of innocent people.

How then are we to respond to the problem of war? How is the Christian to tackle the moral dilemma of resisting evil? In his attempt to grapple with the problem of war, Robert Clouse brings together four differing Christian views on the subject. By allowing four contributing authors to state and defend their respective views, Clouse hopes to give his readers the needed information to make an intelligent choice as to the proper Christian response to war. In a very readable fashion, Clouse introduces the problem of war by briefly surveying the different approaches Christians have taken towards it historically. Beginning with the early church and ending with the present arms race, Clouse considers Augustine’s Just War, the crusade spirit of the twelfth century, the Reformers’ and Anabaptists’ positions and Clausewitz’s concept of the ‘total war’.

The first position to be argued for is by Hermon A. Hoyt. His stance is one of non-resistance. He contends that contrary to much opinion the doctrine of non-resistance is very positive and active. He essentially argues that though the use of force and going to war may be legitimate for government, it is wrong for Christians. The church is separate from the state and thus the method for defence and offence should be different for the believer. Because physical violence is a carnal method and therefore worldly, the believer is forbidden to use it as a method of accomplishing God’s purposes. ‘And if it is wrong for believers to employ physical force to advance spiritual interests,’ says Hoyt, ‘then it is also wrong for believers to join the world in the use of physical force to advance temporal interests.’ From Hoyt’s perspective, non-resistance is not a plank in some political platform. Non-resistance is a spiritual principle which runs throughout the Word of God. As to the wars in the Old Testament, Hoyt argues that the church age of grace is qualitatively distinct from the dispensation of law in which Israel lived and fought. Hence the New Testament advances from justice to love and thus establishes God’s will of non-resistance for all his children. As to the believer’s responsibility to government, Hoyt contends that a Christian’s highest loyalty is to God first, and then to man. Christians, therefore, are responsible to obey their government but only when it promotes God’s will. Since war is evil and obviously opposed to God’s will, the Christian is obligated to refrain from fighting. He may, however, participate as a non-combatant.

The second view to be considered is that of Christian pacifism. Like Hoyt, Myron S. Augsburger questions the moral responsibility of taking human lives for whom Christ died. Because of Christ’s death, every life is ‘of infinite worth’. Augsburger also argues that the way of non-resistance (or pacifism) is a positive and constructive mode of operating in the world. Peace, he argues, is much more than the absence of war. Non-violence is a total way of life touching upon one’s values at every level. The Christian, unlike the secular man, is armed with love, which if given a chance to work will actively and redemptively penetrate society. Only love can counteract the evil violence in the world. Augsburger differs from Hoyt in that he calls for a thoroughgoing and non-discriminate pacifism. The Christian must consciously separate himself from all identification with the world’s military programme. This includes non-combatant associations. Moreover, as a matter of Christian mission he is to call upon the whole of society to lay down their arms. Augsburger agrees with Hoyt that the church is separate from the state, but this does not mean that the principles in the New Testament cannot apply to the world. Pacifism is therefore obligatory for all of human society.

Arthur Holmes takes quite a different view of war in arguing that Christians are obligated to fight in those wars which are just. Holmes denies the radical distinction between the two Testaments and argues that love does not supersede the law of justice. Holmes contends that the teachings of Jesus actually capture the true spirit and intention of the Law; namely, ‘justice tempered by love’. Love, according to Holmes, not only goes the extra mile but also demands the protection of the innocent. Moreover, owing to man’s fallen state, not all evil can be avoided. Every action, no matter how pure the intentions, has some evil results. Thus, a true ethic of right and wrong is more than the matter of good or evil produced. The rightness and wrongness of an act must be viewed deontologically as well as consequentially. For this reason the apostle Paul appeals to the principle of justice in Romans 13 and in so doing gives the government the right and authority to punish evil-doers with the sword. This principle of justice, argues Holmes, is universally binding on all men (Rom. 1–3). In reference to war, this same principle must be applied. Therefore, the just war theory insists that the only just cause for going to war is a defence against aggression. ‘If all parties adhere to this rule, then nobody would ever be an aggressor and no war would ever occur.’ Sticking to Romans 13, Holmes points out that only governments have the right to use force. Because justice tempered by love calls for the protection of the innocent, Holmes forcefully opposes the use of non-strategic nuclear weapons. Holmes is aware that in the present day the application of the just war theory is frustratingly complex. However, the Christian is still responsible to take up arms and help the cause of peace and justice if he can do so in a just fashion. If he cannot, selective conscientious objection is his only other alternative.

A step beyond the just war theory is that of the crusade or preventative war. Represented by Harold O. J. Brown, this position calls for eager participation in war efforts which attempt to prevent or correct outrageous injustices. If self-defence is justifiable, as Brown assumes it is, then under some circumstances a pre-emptive strike must also be justifiable. Severely menacing behaviour is as much an act of aggression as an actual physical first strike. Thus, in principle, one might urge that the best way of preventing war is to be well and fully armed. If one is to have a proper zeal for justice, one may call for a crusade if it should be in one’s power to stop terrible acts of violence. One of the problems with this position is, How can a person know when to fight if he never has all the relevant facts? How can he be held responsible? In answer to this problem, Brown asserts that the moral burden of decision finally rests on the nation’s leaders. Therefore, it is probably best to have Christians in public office, for only they can lay claim to the authority and strength to make proper decisions affecting the nation.

Clouse has done his Christian audience a great service by bringing together various views addressing a very difficult and controversial issue. The strength of the book lies mainly in its format. The various responses and criticisms made by each author helps highlight the theological, philosophical and ethical difficulties with war. However, his book at best only introduces the problems associated with war. Except for Holmes, I found the representative positions lacking in balance, theological precision and exegetical insight. Hoyt and Augsburger fail, for instance, to distinguish between violence and physical force, killing and murder. In addition, Hoyt, Augsburger and Brown fail to show the relationship between love and justice. For Hoyt and Augsburger, love is so far elevated beyond and above justice that justice is left to a place of passé non-relevance. In contrast, Brown so exalts the principle of justice that he leaves the law of love to a select few of pious individuals. In addition to love and justice, such issues as the relationship between special and general revelation, church and state, and Old and New Testaments need much more consideration. Holmes’ article on the just war is particularly well written. Homes introduces his readers to the importance of a sound normative ethic. However, he fails to address the necessity of securing a just means in addition to a just cause. Over-all, this book is introductory material at best. The bibliography at the end of the book is quite helpful but the book itself only introduces the issues and problems with war. One will have to read on if an intelligent and firm decision is to be made.

Charles E. Moore

Denver Theological Seminary