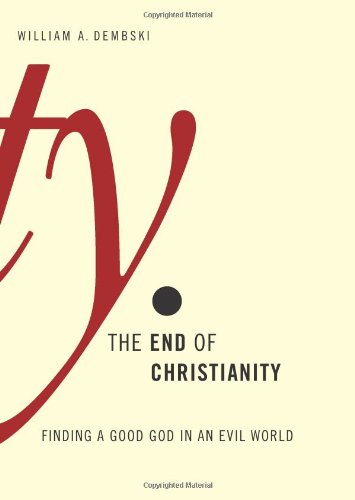

The End of Christianity: Finding a Good God in an Evil World

Written by William A. Dembski Reviewed By William EdgarAlways winter but never Christmas! Thus C. S. Lewis portrays a fallen world in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, the opening volume in his Narnia Chronicles. The Scriptures tell us that the ground is accursed because of human sin and that “the whole creation has been groaning together in the pains of childbirth until now” (Gen 3:17–19; Rom 8:22 esv). The expression “together” is best taken as a reference to the entire creation, that is, the universe in all its parts, which is suffering in birth pangs, waiting along with humanity, which also “groans inwardly” for full redemption (Rom 8:23).

Few Christians have any problem admitting that nature is fallen. From earthquakes to disease and famine, dangerous predators and devastating tsunamis, an empirical look at the creation gives us anything but the peaceful world Rousseau observed in his Reveries of a Solitary Walker (1778). But how does this malevolent condition of the natural world connect to human sinfulness? The difficulty has been compounded ever since the likelihood of an ancient universe has become the dominant view. How can the sin of our first ancestors affect the chaos of the world for thousands of years before they walked on the planet? Most important of all, in the light of nature’s fall, how can we affirm that God is both the good and powerful creator? In a word, we are discussing theodicy. Although the term itself was not coined until G. W. Leibnitz (1646–1716), puzzling out the dilemma of a just God in the face of evil is as old as the ancient writers, who cried out, “Why, O Lord?” (Ps 10:1; Hab 1:13).

William Dembski is well-known in certain circles as the defender of intelligent design. At the same time he is a critic of creationism, which advocates a young earth (reading the days of Gen 1 as comprising only twenty-four hours). In The End of Christianity, he sets himself the task of establishing a theodicy. The curious title is meant to get the attention of those who wish that were true. When they read the book and observe the world, they will have to decide that that was only wishful thinking. Dembski dutifully attacks the new atheists, Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens et al, but his real concern is to mesh the traditional doctrine of Adam’s fall and its effect on nature with the reality of pain and suffering long before Adam.

His basic argument is as follows. The cross of Christ is the answer to the problem of evil. It is also the ultimate demonstration of the goodness (or benevolence, as he prefers) of God in creation. Evil came into the world because of the “personal evil” of the first humans. Although we do not know all of the reasons God could allow natural evil in relation to human sin, the basic one is “to get our attention” (p. 45). That is, the presence of evil in the world underscores the gravity of sin, so that we will be all the more aware of the cost of Christ’s work for our salvation.

Although this approach is fairly common, where things get interesting is the way Dembski connects the evils in nature, which existed long before the creation of humankind, to the sins of our first parents. The problem is that the earth, and its evils, have existed millions of years before Adam and Eve. How can our first parents be a cause, in any meaningful sense, of the evils in a world that they did not inhabit? How could the fall affect not only the future but the past? His answer comes by being able to distinguish between two concepts of time: kairos as opposed to chronos. The first is something like “purposeful time,” whereas the latter is chronological time. He compares the difference to the visible realm and the invisible realm (p. 125). The visible realm operates according to the simple, sequential order of chronological time. But the invisible realm operates according to kairos, which is “the ordering of reality according to divine purposes.”

So how does this help us attribute human sin to the fall of nature well before the existence of humans? Because God is above time, that is, chronological time. God, then, acts by anticipating the fall. He can do this because causality is an infinite dialectic whereby God anticipates novel events by divine action in the realm of kairos, which is not time-bound, and interacts with human agency, which is not predetermined, but free (p. 140). Accordingly, Gen 1 does not record chronological time but purposeful or kairological time.

In the bargain, God remains good and powerful, even though human beings have freely chosen to go astray. Dembski argues that we live in a “double creation,” whereby all things are created twice: first the concept, then the realization. God has a general plan the way a playwright conceives of his theatre, but then the actors must perform. And in the case of the earth, the actors did not perform properly. But that is all right, because God can still “rewrite history” in order to save us. “God can rewrite our story while it is being performed and even change the entire backdrop against which it is performed—that includes past, present and future.” Not only can he thus make the effects of the fall retroactive, but he can (indeed, he must) act to undo the damage (pp. 110–11). And he manages to do this without violating the freedom of the actors.

The argument is intriguing. And the book is quite brilliant, full of learned references to both science and literature, to theology as well as history and mathematics. It is an unusual and creative apologetic. But I am afraid it does not succeed.

For one thing, Dembski never explains the kind of a world we are in, wherein God would make human beings responsible for such a catastrophic disorder as the fall of nature. Although he gives the image of God plenty of mention, he does not explain how human beings were created to be “vice-regents,” ruling the world under God’s greater lordship. Nor does he discuss the mandate to replenish the earth and subdue it (Gen 1:26 ff.). Had he done so it might have supported his argument for the relationship between human action and their implications for the natural realm.

Several other significant problems face us as we interact with Dembski’s fascinating text. The central one is the way he relates the Creator to the creature. Despite claims to the contrary, his God is less than fully sovereign. He is the God of the (Arminian) free-will defense, who creates the world perfect, but leaves it free to wander down the wrong path. God is thus off the hook, and yet he may still intervene for his good purposes. Furthermore, although God is omniscient and omnipotent, he gives up some of that knowledge and power in order to ensure the reality of human experience. God’s power must be “tempered” with wisdom, otherwise it would “rip the fabric of creation” (p. 140). More than that, he can invest the full powers of salvation in his Son because Christ is a unique connector between the human and the divine order of things. How can Christ take on the sins of the whole world when his actual passion was of short duration? Back to kairological time. Because the cross of Christ is only a “window” into a deeper reality of divine suffering, the full sufferings of humanity is somehow funneled into the “mere six hours” of Jesus’ hanging on the cross (p. 21).

It’s a delicate, I would say, impossible dance. Dembski attempts to explain it with the use of various formulas, including what he calls the “infinite dialectic.” Most of them are rather labored attempts at having it both ways: a sovereign God and a free creation. The world is fragile, he asserts, and so lots of causes can bring about lots of effects, but never in a straight line. God intervenes, constantly correcting things, not as a “cause” but as a “cause of causes.” This way his purposes can be fulfilled even though he is working with a strong measure of autonomy. Although different from Karl Barth’s dialectic, it is hard to miss certain affinities.

Of course, autonomy can no more be partial than a woman can be a little pregnant. And God can no more give up his knowledge and power and remain God than a fish can live out of water. To be sure, the problem of relating a responsible human agent to an all-powerful God is very old and very difficult. To have a fully sovereign God will always appear, to our rationalist mind, incompatible with a free creation. Perhaps, indeed, this is the philosophical problem. As K. Scott Oliphint puts it,

The problem is creation. No matter how many or what kind of arguments are given to show the incommensurability, if not the outright contradiction, between God’s essential existence and other aspects of that existence, or other aspects of creation, the tension inherent in every one of these arguments is located in the attempt to come to grips with the relationship of God to creation. (Reasons for Faith: Philosophy in the Service of Theology [Phillipsburg: Presbyterian & Reformed, 2006], p. 209)

Although no one, surely, has all the answers to this relationship, the assertions coming out of the Augustinian and Reformed tradition are more satisfying than many. First, there is a refusal to lessen either “side.” God cannot reduce or even “temper” his knowledge and power and still remain God. At the creation of the world, God invested full significance to the universe without giving up an iota of his omniscience or omnipotence. Even in the incarnation, if we follow Chalcedon, Christ remains truly God, while adding humanity to himself. While he did humble himself and subject himself to the limits of humanness, yet he was able to do so without becoming less God.

So, then, how can the creation have any real significance? The second assertion must be no less firm. There is abundant Scriptural evidence for the reality of human free will. “Choose this day whom you will serve,” Joshua tells the people (Josh 24:15). There are even those remarkable texts suggesting that with respect to human decision, God himself changes his mind, as he did when he regretted having made humanity (Gen 6:6) or when he relented to judge repentant Nineveh (Jonah 3:10). This is a stubborn a biblical fact as God’s sovereignty. It won’t do to try and downplay human agency. If we are sorry, God repents!

So how can this be? In one way, we simply do not know. We’re too limited. Yet we are not entirely without guidelines. What we must assert, somehow, is that God is so powerful that he is able to create a world that is responsible. He does not do this as one might in a human contract: I’ll give you money if you’ll sell me your automobile. There is no trade-off in which God loses something to build a world outside of himself. It is a both-and. The creeds and classic Reformational confessions state that whereas God ordains everything immutably, according to his own free counsel, he does so in a way “as thereby neither is God the author of sin, nor is violence offered to the will of creatures, nor is the liberty or contingency of second causes taken away, but rather established” (Westminster Confession of Faith III.1). The Aristotelian language of “second causes” should not lessen what is being said: the reality, the integrity, indeed, the accountability of causation in the created world are not lessened by God’s omnipotence, but are made possible by it. Mystery? Certainly. Impossibility? Apparently not. Both are true, and require each other.

Another way to put things is to assert that while God does not (and cannot) change ontologically, he does change with respect to his covenant relationship with his creation. The case of prayer may not settle it, but it comes close. Why pray when God not only knows but has determined what is going to come to pass? Because he has established a covenant with his creation whereby he makes it real. So when he answers prayer, it is not a simple case of appearances. He really hears and really responds. And when he regrets or relents, while those are not a contradiction of his being, still they are absolutely real. It’s not as if he were sorry, using human language because he could not actually change. No, he is sorry and does change with respect to human history. We might admit that all of this originates in the secret places where the Spirit and counsel of the Lord cannot be measured (Isa 40:13). So the rationalist mind is ill-equipped to fathom the relationship between God and his creation. But we can be assured there is a reason. Rationalism, no, rationality, yes! Creation is real.

That is why Dembski’s suggestion that God acts backwards in time is not successful. Such an assertion removes the significance of creation. It makes the world malleable with no established second causes. At times this picture resembles Gnosticism more than historic Christianity. Bolstering the argument, as he does, by saying God is above time does not help. Although God is indeed eternal, he has decided to honor his creation by entering into time for its sake. He will not violate earthly sequential history simply to apply judgments or blessings anachronistically. And using, as he does, the case of Israel being saved before the historical event of the atonement is not convincing either. Again, classical theology recognizes that God favored the people of the OT in anticipation of the atonement, but yet their salvation was not actualized until the cross and the resurrection. And it won’t be fully realized, for them or for us, until the resurrection.

So then, how does one explain pain and death in the natural realm before the fall? This one is not so easy either. Perhaps a few remarks can help. The whole question deserves far lengthier treatment than can be given here. First, I do agree with Dembski that the fall of nature must be a consequence of Adam’s sin. That is what the biblical evidence compels us to believe. It would have helped him to show how the image of God requires such a responsibility, as I mentioned above. Second, though, can we be sure that all pain and death in the natural realm are evil, as he argues? If we think so, and if we reject, as I do, Dembski’s idea of applying the fall backwards by anticipation, then we are forced somehow to identify a pre-fallen world without predators, a world without animal death, or perhaps even without death of some flora. I have heard such arguments, and they appear strained, to say the least. Mosquitoes would have stung only leaves, not people! Animals would have lived together in a pre-fallen “peaceable kingdom,” much as they are promised to do later. Volcanoes would not erupt, or if they did, there would be no destruction.

But consider instead the possibility that pain and death is not always a moral catastrophe. Are they not often portrayed in Scripture as part of the way things are? Psalm 104, a commentary on Gen 1, tells us, “The young lions roar for their prey, seeking their food from God,” without a hint of abnormally (Ps 104:21). And where would be the force of one of Paul’s illustrations as he argues for the resurrection, which accuses us of folly if we do not recognize that what is sown does not come to life unless it dies? (1 Cor 15:36). We recently visited a marvelous aquarium on Maui Island. There we saw hundreds of fish cleverly evading their predators and hundreds of others outsmarting them so they could feed. At first, we thought, what a cruel world we are in. Then we thought again: maybe our modern sensibilities are too ready to define the good as simply the absence of predation. Certainly violence among human beings is unacceptable, no doubt a result of the fall. But is the same true for the animal world? Should Christians all be vegetarians? Surely not. That does not mean that all animal suffering is morally inconsequential. Surely there is a line, though, between hunting animals for food and being perversely cruel to them.

Biblical scholars like Bruce Waltke suggest that the creation was “very good” but yet not entirely tame. Even after the creation was finished, there could be what he calls “surd evil,” a hostility to life not connected with sin (see his Genesis [Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2001], p. 68). Going a step further, perhaps this untamed creation is itself a statement, not only of the power of God, but of his purposes. Geerhardus Vos finds an eschatology in the original creation. Although “perfect,” the world Adam and Eve inhabited was not yet fully mature. It required a probation that when passed would lead humanity and the world with it to consummate bliss, eternal life. In the occasion, our first parents failed the test, bringing death and misery into the world, including an intensification of pain in the natural world. But by his great love, God provided another way; the probation was put to his Son, who not only passed, but joined us to himself, now, and then in the resurrection, where there will be no more tears and where death will have no power. Animal death in heaven? We don’t know. Isaiah suggests not, in his account where the wolf and the lamb dwell together (Isa 11:6).

Despite this central criticism, I found much of value in Dembski’s book. My favorite part of his theodicy is what he calls the “problem of good.” Whatever we might think of the way evil comes about, he fully recognizes the intrusion of God’s goodness (his benevolence) into our present fallen world. Though there are Hitlers and Stalins, there are also Wilberforces and Frankls. Even in our dark world, we have many choices and can follow Christ into working for justice and beauty. And there is a lot to thank God for, despite the fall. Dembski eloquently celebrates devotion and self-sacrifice. With Dante he invites the reader to “contemplate with joy that Master’s art, who in himself so loves it that never doth his eye depart from it.” That is the best place to go, when we cannot fully understand all of the Master’s purposes.

William Edgar

William Edgar is Department Coordinator and Professor of Apologetics at Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Other Articles in this Issue

I didn’t come from an Evangelical home, and though he never told me outright, I’m sure my father never wanted me to become a pastor...

Does Baptism Replace Circumcision? An Examination of the Relationship between Circumcision and Baptism in Colossians 2:11–12

by Martin SalterReformed paedobaptists frequently cite Col 2:11–12 as evidence that baptism replaces circumcision as the covenant sign signifying the same realities...

New Commentaries on Colossians: Survey of Approaches, Analysis of Trends, and the State of Research

by Nijay GuptaNew Testament scholarship in its present state is experiencing a time of abundance, especially with respect to biblical commentaries of every shape, length, level of depth, theological persuasion, intended audience, and hermeneutical angle...

It might seem odd to write an editorial for a theological journal on the topic of not doing theology and how important that can be; and, indeed, perhaps it is contrarian even by my own exacting standards...

Most readers of Themelios will be aware that the word “perfectionism” is commonly attached in theological circles to one subset of the Wesleyan tradition...