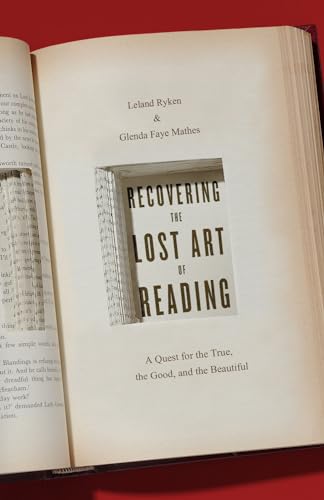

Recovering the Lost Art of Reading: A Quest for the True, the Good, and the Beautiful

Written by Leland Ryken and Glenda Faye Mathes Reviewed By Tony A. RogersIn a day when many seek edification via social media and the smartphone rather than the sonnet, the short story or even the Scriptures, this insightful and inspiring work by Leland Ryken and Glenda Mathes offers a masterful presentation of God’s gift of literature and a clarion call to its revival and renaissance. Ryken is professor emeritus of English at Wheaton College and author of over fifty books; he has frequently written about classic literature from the Christian perspective and the Scriptures as literature. Mathes is a professional writer, adept in numerous genres (fiction, non-fiction, poetry) and media platforms (magazines, newsletters, blogs), who, as an author of over one-thousand articles, seeks to convey timeless truths through literary excellence.

While illiteracy is a growing and grievous issue, the authors believe a more significant concern is “aliteracy,” the ever-increasing number of people who know how to read but never do (p. 17). Their hope is to inform, inspire, and align the way we read, for as they see it, artful reading (reading receptively and thoughtfully) or “deep reading” is in “deep trouble” (p. 23). While people may spend “more time scanning screens … they are spending less time reading literature” (p. 160). As a consequence, we’re “losing depth and wisdom, perhaps even a part of ourselves that jeopardizes our very souls” (p. 160).

The book unfolds in three sections. Part 1, “Reading Is a Lost Art,” gets to the root of the problem. People read persistently online but that does necessitate reading material of worth or reading well (p. 16). Digital reading averages 5.9 hours per day while traditional reading about 1 hour. The cumulative effect is “cursory reading, hurried and distracted thinking, and superficial learning” (p. 21). The believer’s devotional life suffers, for we “lose the ability to read the Bible consistently and attentively” (p. 24), as well as our walk with God. Part 2, “Reading Literature,” provides a rationale for reading literature and offers instruction on how to enjoy several distinct types: stories, poems, novels, fantasy, children’s books, and creative nonfiction. These various areas of literature “can be briefly defined as a concrete, interpretive presentation of human experience in an artistic form” (p. 61). Reading widely “offers us meaningful leisure at contemplative, intellectual, imaginative, and spiritual levels.” (p. 78). Part 3, “Recovering the Art of Reading,” offers a reasoned strategy for this pursuit. Prior to recovery, there must be an acknowledgment of the problem. This will lead to an assessment of one’s reading habits and the reading of good literature—works which reflect (or remind us of) scriptural values, thereby enhancing our spiritual walk (p. 167). Other recovery suggestions include the practice of rest, never leaving home without a book, forming good habits, and avoiding time thieves—“the most insidious and common ones have a screen” (p. 217).

Of the book’s twenty-two weighty chapters, three bear a further look. Chapter 1 answers the question, “What Have We Lost?” Francis Bacon asserted that reading makes a full person. But when humans refuse the gift of literature, what do they forfeit? The answer is sevenfold: (1) meaningful leisure; (2) self-transcendence; (3) beauty; (4) contact with the past; (5) contact with essential human experience; (6) edification; and (7) enlarged vision.

Chapter 5 asks the question, “Why Does Literature Matter?” To be sure, “Scripture does more than sanction literature; it shows us that literature is indispensable in knowing and communicating our most important truth” (p. 64, emphasis original). Literature matters because: (1) it conveys knowledge and confers delight; (2) seeing human experience and the world accurately matters; (3) it can help shape us into thinking people, armed with God’s answers to life’s questions; and (4) we need artistic beauty to live happily and fully.

A major surprise was chapter 11, “Reading Children’s Books.” Gone are the days when children’s books conveyed biblical values and pictures of God. Parents must be on the alert and guide their children’s reading, for “children’s literature [has an] incredible capacity to shape impressionable young minds” (p. 122, emphasis original). The authors offer tips on choosing good books, a comprehensive nurturing style based on Deuteronomy 6:6–9, and a stern warning that technology is not just a thief of our children’s time, but also of their childhood (p. 133).

This work highlights a pair of biblical/theological emphases and their relation to literature. The first is the Imago Dei. God said, “Let there be … and it was so … and it was good,” and as God’s image-bearer, man possesses the prospect of creating and delighting in the beautiful (p. 31). While every reader can delight in literature’s beauty, only Christians can “experience beauty on spiritual levels that point to God. In the words we read, we often see dim reflections of the One who created by his word and the Living Word, Jesus Christ” (p. 200). Second, as the subtitle suggests, the authors define the quest for the true, the good, and the beautiful—the three inextricably linked transcendentals that echo the very character of God (p. 164). To determine the true, one must test the literary work’s truth claims against what the Scriptures and Christian doctrine say about like subject matter (p. 175). To determine the good, “we also need to exercise this comparative process to assess the moral claims in a work of literature. The more our literary excursions send us to the Bible, the better we expand our grasp of Christian ethics” (pp. 186–87). To determine the beautiful, we first need to recognize that beauty matters to God, for God is the ideal and radiance of true beauty, and graciously imparts this gift for the sensory pleasure and spiritual delight of humanity (p. 198).

It may surprise those who employ a literal/natural hermeneutic that the authors deem that the “hundred-pound hailstones of the Apocalypse [that] picture the coming cataclysmic destruction of the earth” (Rev 16:21) belong to the genre of “fantasy” (p. 115). The authors define fantasy as “not simply fictional or made-up as opposed to being historically or empirically factual” (p. 112). Does Revelation’s use of apocalyptic imagery mean that the only interpretive option one is left with is that of “imaginary hundred-pound hailstones” (p. 115)? I would answer in the negative.

This uncertainty notwithstanding, this magnificent volume will prove beneficial for all lovers of Scripture, for “who should care more about reading timeless truths than children of the Book?” (p. 24). Those with a particular interest in literature, especially Christian literature, will welcome this addition to the growing body of evangelical treatments of the arts. For further study one may read Leland Ryken and Tremper Longman’s A Complete Literary Guide to the Bible (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Academic, 1993) or Frank Gaebelein’s classic, The Christian, the Arts, and Truth: Regaining the Vision of Greatness (Sisters, OR: Multnomah, 1985). We need to recover the lost art of reading, for the quest for the true, the good, and the beautiful is ultimately the quest for God.

Tony A. Rogers

Tony A. Rogers

Southside Baptist Church

Bowie, Texas, USA

Other Articles in this Issue

Exclusion from the People of God: An Examination of Paul’s Use of the Old Testament in 1 Corinthians 5

by Jeremy Kimble1 Corinthians 5:1–13 serves as a key text when speaking about the topic of church discipline...

Is it possible to speak of a real separation between Jewish and Christian communities in the first two centuries of the Christian era? A major strand of scholarship denies the tenability of the traditional Parting of Ways position, which has argued for a separation between Christians and Jews at some point in the second century...

A Tale of Two Stories: Amos Yong’s Mission after Pentecost and T’ien Ju-K’ang’s Peaks of Faith

by Robert P. MenziesThis article contrasts two books on missiology: Amos Yong’s Mission after Pentecost and T’ien Ju-K’ang’s Peaks of Faith...