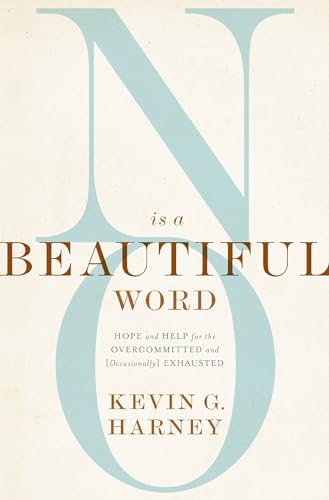

No Is a Beautiful Word: Hope and Help for the Overcommitted and (Occasionally) Exhausted

Written by Kevin Harney Reviewed By William VanDoodewaardKevin Harney is perhaps best known for his teaching encouraging Christians to reach out and proclaim the gospel to their co-workers, neighbors, and friends through organic relationships and conversations. His most recent book, No Is a Beautiful Word, is a fascinating, unique, and challenging book in the genre of David Murray’s Reset (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2017), Kevin DeYoung’s Crazy Busy (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2013), and Greg McKeown’s Essentialism (New York: Crown, 2014). While having some similarities to these volumes, Harney provides a fresh vantage through the window of that little word we all use: “no.” If you are looking for counsel to help you gain greater balance in re-entry to a busy life, or in re-thinking the motivations and character of your communication, this is a great place to start.

No Is a Beautiful Word is immediately engaging. Rich with personal anecdotes, it is like a conversation with a wise friend who is also a master storyteller. Opening with a description of a buffet, Harney describes a multitude of attractive options: “despairing, you know that you can’t have it all. You’ve loaded your plate, mixing several dishes together, filling and squeezing in as best you can. But there just isn’t room. Your plate is full” (pp. 17–18). He goes on to share, “there is an art to dining at a buffet. Few have mastered it. It demands superhuman restraint” (p. 18). This is too often like our lives. Our plates are full, our margins are thin—at times to the extent that we can’t “add one more responsibility, help one more person, squeeze in one more meeting, or volunteer one more minute without something falling off” (p. 18). If we are weary and overextended, “longing for more time, margin, peace and productivity,” then Harney calls us to realize “it is time to discover a simple but profound truth … no is a beautiful word” (p. 19).

Harney shares that the book was a long labor of love, with the aim of helping the reader not only see the value in saying no, but also “learning to love saying no” (p. 20). The goal in doing so is not ultimately negative, but to give space for “an essential and life-changing yes” (p. 25).

The first part of No Is a Beautiful Word seeks to define what it is to say no, and how “no” can be good, beautiful, and a godly expression of conformity to Christ. Harney provides a compelling beginning point here for the rest of the book, but there are two areas where it could be better. The first would be to avoid using the movie Bruce Almighty—which many Christians see as blasphemous—as a positive illustration. The second would be to move beyond the exemplary description of Jesus’s use of “no,” to explicitly root the book in the gospel, using passages like Philippians 2:7 and others to show our Savior’s willingness to say no to his prerogatives, even as he fulfilled the redemption that is God’s marvelous yes to us.

The second part of the book is titled “Know Your Nos.” Here Harney shares excellent advice about how to fit our nos to the occasion. He notes there are “many ways to say no” (p. 45) and walks the reader through scenarios providing a variety of ways of saying no in the best possible way. Harney’s sample nos range from “No, never, I’m offended you asked me, and don’t ever ask me again” to “no, but I love what you are doing.”

The third section of the book, “Picking Your Nos,” continues the theme of part two, but now with a focus on wisely selecting “which no is right for each of life’s situations” (p. 88). Part of Harney’s emphasis in this section is on connecting the manner of saying no with the occasion. The same is true of part four of the book: “No Strategy.” Here Harney helps us see that we can grow in saying no well: “it is a strategic learning process” (p. 110). Whether it is saying no with kindness, or realizing that we do not need to apologize when we say no for good reasons, Harney again gives thoughtful and engaging counsel on how and why we should say no. The same is true of part five, “Critical Nos,” and six, “No Results.”

The fitting capstone of the volume comes in part seven, “The Freedom of Yes.” You might wonder whether an entire book focused on the use the word “no” would be worth reading: my answer is “yes”! While I wish it had a more substantive gospel content, the book captivated me. Harney subtitled his book, Hope and Help for the Overcommitted and (Occasionally) Exhausted. He has admirably achieved both, teaching us a basic life lesson many of us need to be reminded of—a wise “no” really is a beautiful word.

William VanDoodewaard

William VanDoodewaard

Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary

Grand Rapids, Michigan, USA

Other Articles in this Issue

The concept of personhood is crucial for our understanding of what it is to be human...

Text-Criticism and the Pulpit: Should One Preach About the Woman Caught in Adultery?

by Timothy E. MillerThis article considers whether “The Woman Caught in Adultery” (John 7:53–8:11) should be preached...

Celebration and Betrayal: Martin Luther King’s Case for Racial Justice and Our Current Dilemma

by James S. SpiegelDuring the American Civil Rights Movement, Martin Luther King’s principal arguments reasoned from theological ethics, appealing to natural law, imago Dei, and agape love...

Many churches switched to streaming or recording their services during the COVID-19 crisis...