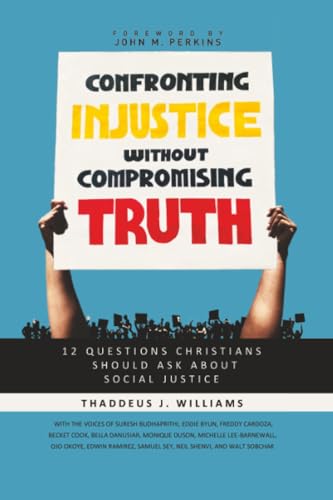

Confronting Injustice without Compromising Truth: 12 Questions Christians Should Ask about Social Justice

Written by Thaddeus J. Williams Reviewed By Neil Shenvi“God does not suggest, He commands that we do justice” (p. 2, emphasis original). Thaddeus Williams, associate professor of theology at Biola University, reminds us of this truth in his new book Confronting Injustice without Compromising Truth. But what is justice? And how can we distinguish true justice from its counterfeits? Unpacking those questions takes several hundred pages, but the result is convincing, accessible, and sorely needed. Civil Rights leader John Perkins, who wrote the book’s forward, warns us that in the midst of “much confusion, much anger, and much injustice … many Christian brothers and sisters are trying to fight this fight with man-made solutions [that] promise justice but deliver division and idolatry [and] become false gospels” (p. xvi). Williams’s book is a must-read for those trying to understand these false gospels, especially high school and college students who feel torn between conservative Christian theology and a passion for activism.

In his introduction, Williams contrasts two different visions for “social justice,” dubbing them “Social Justice A” and “Social Justice B.” Social Justice A refers to the application of biblical principles to society’s laws, as exemplified in the lives of William Wilberforce, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and Sophie Scholl. It describes Christian efforts to “abolish human trafficking, work with the inner-city poor, invest in orphanages, upend racism, and protect the unborn” (p. 4). Despite the understandable discomfort many evangelicals feel with the term “social justice,” it has historically been used by Christians to refer to activities that are mandated by Scripture.

In contrast, Social Justice B refers to the “‘oppressor vs. oppressed’ narrative of Antonio Gramsci and the Frankfurt School, the deconstructionism of Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida, and the gender and queer theory of Judith Butler” (pp. 4–5). It thus describes a movement that is often diametrically opposed to a biblical worldview, both in theory and in practice.

In the subsequent chapters, Williams asks twelve penetrating questions that expose the stark differences between Social Justice A and Social Justice B, probing everything from their assumptions about identity and morality to their attitudes towards truth, tribalism, and unity.

The divergence between Social Justice A and Social Justice B begins at the most fundamental level. While secular theories of justice must necessarily start with horizontal relationships between humans, a biblical conception of justice starts with our vertical relationship to our Creator. “If justice means giving others their due,” then justice demands that God be given his due, for he “is due everything” (p. 18, emphasis original). Williams points out that all of history’s worst injustices were the product of fallen human hearts in rebellion against God: “Look deep enough underneath any horizontal human-against-human injustice and you will always find a vertical human-against-God injustice, a refusal to give the Creator the worship only the Creator is due. All injustice is a violation of the first commandment” (p. 18).

Establishing a proper theological foundation is crucial because “[t]here is simply no worldview-neutral way to think about or act out justice” (p. 7). This is why people on both sides of a range of controversies “believe they are fighting for justice” (p. 6). For example, pro-choice “reproductive justice” is a major component of Social Justice B while pro-life opposition to abortion is a major component of Social Justice A. Why? Not because one side believes they are fighting for injustice, but because each side has a different understanding of what justice entails. What is a human being? What is the basis of human value? What are our moral duties? Far too often, Christians want to dive into activism, skipping past these “theoretical” issues. But they’re inescapable. If we ignore them, we might find ourselves doing great evil in the name of “justice.”

From a Social Justice A perspective, our fundamental problem as human beings is sin and the fundamental solution is redemption through Christ. Of course, Williams reminds us that individual human sinners can and do create unjust systems: “From steep interest rates to ritual child sacrifice, the Bible has much to say about confronting the kind of injustice that is bigger than this or that individual sin” (p. 79). But the problem begins with the individual human heart, even if it doesn’t end there.

In contrast, Social Justice B locates our social problems primarily in groups. It thus “attempts to explain the world’s evil and suffering by making group identities the primary categories through which we interpret all pain in the universe” (p. 61). Yet does such “collectivist group blaming” lead to justice or to internecine group conflict? In answering this question, Williams references a 2018 Washington Post article by Suzanna Danuta Walters entitled “Why Can’t We Hate Men?” which included lines such as “Is it really so illogical to hate men?… when they have gone low for all of human history, maybe it’s time for us to go all Thelma and Louise and Foxy Brown on their collective butts” and “please know that your crocodile tears won’t be wiped away by us anymore. You have done us wrong” (cited on p. 57). The point of the article, like that of several others that Williams references, is clear: Instead of seeing all human beings as guilty sinners before a holy God, Social Justice B encourages us to cast certain groups as villains and others as victims. This is hardly a pathway towards unity.

The narrative of Social Justice B will also prescribe a certain perspective towards group disparities. As best-selling author Ibram X. Kendi wrote in the New York Times, “racial disparities must be the result of racial discrimination…. When I see racial disparities, I see racism” (cited on p. 81). Yet in chapter 7, Williams provides examples of how the real world is far more complex than this simple formula implies. For example, “twenty-two of the twenty-nine astronauts in the original Apollo space program were firstborns.… Asians are underrepresented in the NBA.… Women are overrepresented in health-care.… Jewish people … received … 32 percent of Nobel Prizes in medicine and 32 percent in physics” (pp. 82–83). In few if any of these cases do we think discrimination is the sole or even the predominant explanation for these disparities.

To be clear, Williams is not denying that discrimination can play a role in disparities, possibly even a large role. He is simply pointing out that it is possible to become so enamored of the heroic, liberatory narrative of Social Justice B that we bypass available evidence, or even dismiss appeals to evidence as a veiled attempt to justify oppression. Williams cautions us to resist this temptation: “We can’t separate the Bible’s commands to do justice from its commands to be discerning” (p. 3).

To this end he offers a helpful suggestion: “Before assuming you are ‘woke’ on issues of systemic injustice, I suggest reading at least one or two books about racism that challenge the dogmas of Social Justice B…. The best way to avoid being taken in by dangerous, one-sided ideologies is to expose ourselves to different perspectives” (p. 100). Especially important is Williams’s insistence that he is not attempting to rein in Christians’ desire for justice, but rather to point it in the right direction. If we misdiagnose the problem, then our solutions will be ineffective at best and harmful at worst.

A final, crucial element of Social Justice B is the exalted role played by “lived experience.” According to Social Justice B, people from dominant, oppressor groups (men, whites, heterosexuals, the rich) are supposed to defer to the experiential authority of people from subordinate, oppressed groups (women, people of color, LGBTQ people, the poor): “Those on the oppressed side of the equation are often granted automatic authority” (p. 156). Yet this framework has several problems.

First, while Christians can and should listen to and learn from people with different experiences than our own, someone’s race, class, or gender does not determine whether their claims are true or false. Instead, we must test everyone’s claims against reason and evidence.

Second, in an attempt to defend the experiential authority of oppressed people, proponents of Social Justice B will sometimes make extraordinarily insulting claims, like Judith Katz’s assertion that “‘objective, rational, linear thinking,’ ‘controlled emotions,’ ‘the scientific method,’ and ‘quantitative research’ are all defining marks of racist ‘white culture’” (cited on p. 146). In reality, rational thought and reliance on evidence are human universals, not the property of white, Western males. To say otherwise is to demean myriads of brilliant black and brown innovators, scientists, and scholars throughout history.

Finally, surveys show that there is no single, monolithic voice of color. For example, “less than one-in-three black people without college degrees believe their race has made it harder for them to succeed (29 percent), while 60 percent believe ‘race has not been a factor in their success of failures’” (p. 98). Noting that phrases like “white privilege” and “white fragility” were coined by whites, Williams drily comments: “it is possible that what is often considered ‘the black voice’ is actually the white liberal voice” (p. 98). What is true for the average “man on the street” is true for intellectuals too: “When Social Justice B advocates call for more ‘voices of color’ to be centered in our schools, our diversity seminars, and our political platforms, it is clear that they don’t want voices of color like Sowell’s or the many brilliant black thinkers like him [e.g., Walter Williams, Shelby Steele, Glenn Loury, John McWhorter, and Coleman Hughes] who question the worldview of wokeness” (p. 100).

This point is driven home in a series of brief personal essays scattered throughout the book. In these contributions, people of color (myself included) offer perspectives that don’t easily fit into the Social Justice B narrative. Edwin Ramirez muses, “Though I considered myself woke, my bitterness towards white people had closed my eyes to God’s marvelous saving power in the gospel” (p. 52). Monique Duson explains how Critical Race Theory pulled her towards partiality: “with my black Christian friends, speaking of whites in derogatory ways was perfectly acceptable. I spoke words over whites that Christ would never speak over me. CRT made it nearly impossible to see white people as beloved image-bearers whom Christ died to redeem” (p. 108). Freddy Cardoza laments, “I have become a pariah in many circles [because] I reject today’s trending justice ideologies. The intensity of attacks on people who reject identity-based tribalism has become a spiritual pathology in many Christian institutions” (p. 159).

If we really are committed to “listening to voices of color,” we need to listen to all such voices, not just those which fit into our preferred liberal (or conservative) framework.

In the preface, Williams explains his motivation for writing: “I care about God, I care about the church, I care about the gospel, and I care about true justice…. Not all, but much of what is branded ‘social justice’ these days is a threat to all four of those things I hold dear” (p. xviii). I concur. Evangelical Christians have struggled to articulate exactly what is wrong with the secular social justice movement in a way that is irenic, passionate, and non-partisan. This book is a big step in that direction.

Neil Shenvi

Neil Shenvi

The Summit Church

Durham, North Carolina, USA

Other Articles in this Issue

Exclusion from the People of God: An Examination of Paul’s Use of the Old Testament in 1 Corinthians 5

by Jeremy Kimble1 Corinthians 5:1–13 serves as a key text when speaking about the topic of church discipline...

Is it possible to speak of a real separation between Jewish and Christian communities in the first two centuries of the Christian era? A major strand of scholarship denies the tenability of the traditional Parting of Ways position, which has argued for a separation between Christians and Jews at some point in the second century...

A Tale of Two Stories: Amos Yong’s Mission after Pentecost and T’ien Ju-K’ang’s Peaks of Faith

by Robert P. MenziesThis article contrasts two books on missiology: Amos Yong’s Mission after Pentecost and T’ien Ju-K’ang’s Peaks of Faith...