Volume 13 - Issue 1

The priority of Jesus: a look at the place of Jesus’ teaching and example in Christian ethics

By Melvin TinkerIntroduction

It is not unusual to come across the rule-of-thumb advice: ‘Do what Jesus would have done’, being given to a Christian facing a particular moral problem. Initially at least, this might appear as ‘wise counsel’; after all, what could be better than to appeal directly to the example of the Master himself? Indeed, it is the apostle Peter who urges Christians to follow in Christ’s footsteps (1 Pet. 2:21), and this means working out the Christ-pattern in the rough and tumble of day-to-day existence. But for all its immediate attractions, not least that of simplicity (and it is important that we do not complicate matters unnecessarily), such a recommendation requires more of the Christian than might appear at first sight.

Without wishing to deny the charismatic experience of direct guidance by the Holy Spirit on matters of morality (which even John Wimber admits can sometimes be due more to indigestion than the Third Person of the Trinity!),1 there is a tendency to respond to such advice simply by allowing the imagination to sketch rather hazy and romantic pictures of Jesus moving about in the situation within which we find ourselves, and almost magically handling the problem in question.2 But as Os Guiness points out in another context,3 which Jesus are we thinking of? Our picture of Jesus might be as far removed from the portrait of Christ in the Bible as was the ‘Gentleman Jesus’ of the Victorian drawing room. After all, we are well aware that both ‘Jesus the pacifist’ and ‘Jesus the revolutionary’ have their advocates. If all were to be left at the level of sanctified imagination, then the charge that where you get ten Christians together you will find eleven different opinions might not be wide of the mark.

In point of fact, far from short-circuiting ethical thinking, trying to discern ‘what Jesus would have done’ requires a good deal of careful application. It involves cultivating a familiarity with the sort of things Jesus said and did during his earthly ministry—the principles he enunciated, the way he responded to moral matters, the pattern of behaviour he established, and so on—all this providing some of the raw material out of which guiding principles might be forged. Even so, this is only the beginning, for there is one major fact which has to be faced, the glaringly self-evident one that there is an historical and cultural distance between the world of Jesus and our world today. Although this point may be deemed as ‘self-evident’, it is one which can surprisingly be passed over with remarkable ease in Christian ethical thinking. Jesus did pronounce on matters which prima facie have no direct relevance for us today (e.g. paying the temple tax, Mt. 17:22f.; walking the extra mile, Mt. 5:41f.). What is more, we have to face ethical dilemmas which the teaching of Jesus could not directly address because they arise out of recent technological developments (e.g. in vitro fertilization, genetic engineering, nuclear warfare). Without lapsing into the irresolvable cultural relativism of the sort in which Nineham finds himself,4 such factors should put us on our guard against assuming that with the teachings and example of Jesus we can, with the odd adjustment made for minor cultural differences, make a point-for-point direct transfer to our present situation without engaging in some of the rigorous hermeneutical groundwork of the sort suggested by Marshall.5

There are two important questions raised by the type of considerations outlined above which form the primary focus of this study, viz. 1. To what extent is moral authority to be attached to the actions and teachings of Jesus for our guidance today? and 2. how are those actions and teachings to be appropriated in the service of ethics? In short, how are we to conceive of the priority of Jesus in Christian ethics? In an attempt to move towards answering these questions, five interrelated areas of thought will be explored:

- The basic features of Christian ethics. This will provide the wider perspective against which the teachings and actions of Jesus can properly be considered, while at the same time not losing sight of the fact that the words and deeds of Jesus are themselves constitutive of that perspective.

- The nature of Christ’s ethical teaching and how it contrasts with legalism.

- Christ as exemplar. What this means and an assessment of the peculiar epistemological problems it raises.

- The extent of the moral obligation attached to the teachings of Jesus. This will be specifically linked to a moral decision-making process.

- The relation between ‘Creation ethics’ and ‘Kingdom ethics’.

Although in this study a wide range of discursive material will be considered, the main objective is a practical one, namely to determine how we might more effectively understand, and get to grips with, ethical problems in the light of Jesus’ teaching and pattern of life, and so take up the call of the one who said, ‘Come, follow me’.

Features of Christian ethics

Creational

It is proposed that the starting point for Christian ethics is God and his will for creation, and in this sense one may refer to Christian ethics as ‘creational’ in design and foundation, with their focus upon the moral ordering of the world which in turn is related to the character of God and the nature of man. Such ‘creation ethics’ need to be distinguished from what is often referred to as ‘natural law’, the difference lying in the epistemology of the two approaches.6 Natural law, which plays an important role in Catholic moral theology,7 has a prestigious history with a lineage extending back through Thomas Aquinas to Aristotle. It takes as its basic premise the belief that God has so shaped human nature that it is only by leading a moral life that this nature can achieve satisfactory realization. Following on from this, natural law theory claims that it is possible to read off from these ‘givens’ of human nature the sort of moral imperatives God may have set and which are necessary to follow if one is to move towards real human fulfilment.

Without denying natural law’s fundamental premise, one is forced to question the extent of its usefulness and the validity of its epistemology. In the first place it falls foul of what G. E. Moore called the ‘naturalistic fallacy’. This makes two complementary points. The first is that such a position assumes that it is possible to derive what man ‘ought’ to do from what man ‘is’. But as David Hume aptly demonstrated, this simply cannot be done without having already built into the situation moral assumptions from the start. Thus what ‘ought’ to be done is brought to a factual situation (what ‘is’) and is not deduced from it. The second point involves taking the step of defining ‘good’ in terms other than of itself, e.g. ‘the pursuit of happiness’ or ‘the realization of man’s God-given potential’. But as Moore went on to show,8 while what is ‘good’ may also be something else (happiness, fulfilment, etc.), it cannot be defined by that something else, i.e. placed within the same category of meaning (such that good means happiness). The fallacy is revealed by a simple test. If it is being claimed that one should follow a particular course of action because, say, it ‘maximizes human happiness’, one can ask ‘Why?’ What reasons can be given to convince me that I should do this? Although a variety of subsidiary reasons may be adduced to support the original contention, such as ‘that social stability will be secured’, eventually an appeal will be made to the belief that we should do it because it is ‘good’. If by this the person is maintaining that good means the particular goal envisaged, then it is reduced to the level of trivial tautology. For example, if good means human happiness, on purely linguistic grounds this amounts to saying no more than that human happiness is human happiness. But if not, then it has to be conceded that what is ‘good’ is irreducibly something other than ‘human happiness’, although related to it, having its own moral category of meaning.

In the second place, even if one were to grant that a phenomenal approach to morality, rather than a largely philosophical one, could be harnessed in the service of natural law,9 establishing that moral experience is universal (man does have a moral sense) and that there is a certain amount of agreement between different cultures over what actions are right and which qualities are good, giving moral content to form,10 one is still left with what are at best broad generalizations as well as a fair degree of cultural diversity; and one is forced to ask with Paul Ramsey,11 what is particularly Christian about the results?

The alternative approach being advocated here begins with God and his revelation, together with a consideration of moral experience (itself validated by Scripture, the locus classicus being Rom. 2:14–16), and then moves towards moral imperatives which are grounded in and proceed from the Divine Creator. This is not to suggest that ethics cannot in the first instance exist independently of theology: quite clearly they can and do for many people,12 but rather that Christian theism provides ethics with a ‘metaphysical home’ and substantial coherence when related conceptually to other elements within the Christian framework.13

However, it could be objected at this point that by opting for an ethic which is creational, established by special revelation, one has left unresolved a dilemma classically formulated in Plato’s Euthyphro, viz: ‘Does God will a thing because it is good, or is a thing good because God wills it to be so?’ To opt for the former would mean surrendering the ‘Godness of God’, for it would be to admit another principle outside of God to which he must conform (‘Goodness’). But to go for the second horn of the dilemma would mean that in principle ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ are merely products of arbitrary will. David Brown argues that it is by adopting a naturalist position, rooted in natural law theory, that a resolution of this j problem is possible.14 He maintains that God, by ordaining man’s natural capacities in such a way that only by leading a moral life can they be fulfilled, has made it possible to ascertain what is right or wrong without direct reference to his will, and so they cannot be considered arbitrary. On the other hand, there is an ultimate connection with God’s will in a way which is not arbitrary, because human nature and morality are linked to God’s loving concern for man. But it is difficult to see how this solves the problem. What it does is to push it further back, for one can ask whether God willed the fulfilment of human nature and ordered it in such a way because it is good, or whether it is good because he willed it? The dilemma remains but in a different form. A much more satisfactory answer has been proposed independently by White15 and Ward,16 who in different ways postulate that what is good (Ward’s ‘realm of values’) is also what God wills and what God wills is also good, the two ultimately residing in the being of God as two aspects of the same reality. Thus, far I from creation ethics being arbitrary, they are consistent with the loving purposes of God and the nature of man as he intended.

Taking the link between a moral universe and the Moral Creator a stage further, one can suggest that God is the Good, not in some abstract Platonic sense, but as the personal revealing God who is the ground of all goodness (cf. Mk. 10:18f.). Consequently what are perceived as moral imperatives, instances of goodness in obligatory form, are different aspects of this one unitary reality—the Good. It follows that those attitudes and modes of behaviour which are considered ‘virtuous’ amount to the correct and appropriate responses of man not only to the way things really are, but also to the God in whom the perceived values of goodness and rightness reside and find complete resolution.

Covenantal

Central to both the OT’s and the NT’s understanding of the relation between God and his people is the concept of ‘covenant’. Some, like Karl Barth, would go further in claiming that covenant is central to the understanding of the whole of God’s dealing with creation in that ‘Covenant is the internal basis of creation and Creation is the external basis of covenant’. In establishing his covenant God does so in an act of gracious freedom as classically formulated in Deuteronomy 7:7: ‘It was not because you were more in number than any other people that the Lord set his love upon you … it is because the Lord loves you’. Running throughout his covenant (berîṭ) with his people, and establishing it, is the gracious love of Yahweh (ḥeseḍ). Although God’s covenant in promisory form is to be found in his dealings with Abraham (Gn. 15:18) and David (2 Sa. 23:5), it is particularly in the book of Deuteronomy that the concept takes on a role of tremendous theological significance,17 encompassing in both form and content the mutual obligation of those involved. The actual stipulations of the covenant which were binding upon Israel are set out in the form of a written ‘law’ (tôrāh) (see Dt. 4:44). In fact so close was the connection in the minds of the people between law and covenant, that to obey the law was to obey the covenant (cf. Je. 11:1ff.). What is more, the implications of such a relationship established by covenant were to penetrate every area of life as is evidenced by the Holiness Code of Leviticus 19—any sacred/secular division with which we are only too familiar was ruled out on the basis of the berîṭ(something which the prophets had to continually remind the people, cf. Is. 1:10–26).

It was with the Deuteronomic covenant in mind that Jeremiah, in the midst of national apostasy and defeat, made the innovatory declaration that a new covenant would be made, with the law written upon the people’s hearts (31:31ff.), a promise also taken up by Ezekiel (36:26). However, it was in the person and work of Christ that this promise was to become a reality, establishing a kainē diathekē (Lk. 22:20), a ‘new kind of covenant’ of the type envisaged at a distance by Jeremiah. To those under the freedom of the ‘law of Christ’ comes the obligation to fulfil it in neighbourly concern (Gal. 6:2) and to exhibit a life characteristic of the people of God called to be holy (1 Pet. 2:9ff.). To modify Barth’s phrase it becomes clear that covenant is the internal basis for Christian ethics (its motivating principle and frame of reference) and ethics is the external manifestation of and response to God’s covenant.

Objectivity

Another important claim of Christian ethics is that morality is objective, not only insofar as there is a phenomenon called moral experience, but that matters of right and wrong have an existence and meaning independent of our evaluation of them. This is indicated by the fact that such matters are the subject of discussion with reasons being given for why we think a particular action to be right or wrong, something we don’t do when things are solely a matter of subjective preference (e.g. taste). This is what Baelz calls the ‘logical impartiality of ethics’.18 All of this accords with what has gone before—that goodness and rightness are expressions of the nature and character of God, distinct from the created order and yet manifest in and through it.

Teleological

By using the term teleological it is being claimed that Christian ethics are primarily purposive, ordered towards a goal. What is good for man is related to the type of creature he is and the purpose for which he was made, and it is here that the premise of natural law finds its place, not as a means of determining moral imperatives without reference to God, but as an indication that true fulfilment lies outside of man in relation to God. The naturalist approach of Brown is in grave error of giving the impression that the final end of man is to be found within man (the fulfilment of his nature by living the moral life), thus opening the door for a new form of Pelagianism. Rather, the final end of man as witnessed to by moral experience and special revelation is that it is something which is over and above him, which makes its claim upon him, and this is God himself, the ‘summum bonum’. Ward puts it well: ‘For theism, God is the purpose and inner nature of all being; he is the ontological base of reality; and to respond to him is to respond to being’s real nature’.19

It is this goal and the eternal context in which it is framed that determines much of the content, rationale and direction of Christian ethics, and which marks it out from many other ethical frameworks. This should put the Christian on his guard against making superficial comparisons with other ethical beliefs and cause him to delve a little deeper into what is being proposed. For example, the utilitarian principle of ‘the greatest good of the greatest number’ might at first sight seem attractive and compatible with Christian ethics, but the Christian would want to ask: a. How is the ‘greatest good’ to be understood? b. How does it relate to the goal of developing man’s relationship with God? and c. What difference in perception is made when the claim is placed within an eternal context?20 What is more, the view that the primary end of the moral life is not to be found solely within the nature of man qua man, but in responding appropriately to the Creator (which itself is part of being true to our nature), means that however much in practice theology is separated from ethics (and vice versa!), it is a division which is not warranted by the biblical witness and which if pursued will always result in an inadequate ethic, one which leaves a major part of reality out of its reckoning (in fact the grounds for reality—God).

Attitudinal

The final mark of Christian ethics is that they are attitudinal, having a concern for character and attitudes and not simply with the observance of external moral rules, which can become ends in themselves (cf. Mt. 23:23). Christian ethics go deeper than this in that they are to do with man’s response to God and his attitude toward his fellow men and creation. The upshot of this is that Christian ethics are more ‘open-ended’ than legalism or casuistry, going beyond fixed points (cf. Mt. 5:21–22).

The above is not meant to be an exhaustive or even a comprehensive list of the components of Christian ethics, but an indication of those features which are central to its composition and which form a backdrop against which the teachings and example of Jesus can be properly viewed and understood and against which a moral decision-making process can be developed.

Jesus and ethics—the teaching

In turning to Jesus’ ethical teaching three preliminary points need to be made. The first is that Jesus’ view of ethics is firmly rooted in the OT. The disparity between Jesus’ ethical teaching and that enshrined in the ‘law and the prophets’ is, as we shall see, more apparent than real. Indeed, for Jesus the whole of the law was summed up in nuce in the dual requirement of loving God and loving one’s neighbour (Mt. 22:37–39), which itself comes from the torâh (Dt. 6:5; Lev. 19:18). This is also a clear indication of the theocentricity of Jesus’ ethics and eschatology.21 This is particularly related to the central message of Jesus’ proclamation concerning the kingdom of God. In the person and work of Christ this reign had begun and carried with it its own ethical demands (Lk. 3:10ff.). Yet although the kingdom had been inaugurated by Christ, its consummation lies at some point in the future, the nature of which should have a determining effect upon the way the members of the kingdom act in the ‘mid-time’ (Mt. 6:19; 25:31ff.). Far from Jesus presenting an ‘interim ethic’ as suggested by Schweitzer,22 it is an authentic and lasting ethic appropriate to the reality and demands of the kingdom. Finally, arising out of the last point, the ethics of Jesus is an ethic of the Spirit.23 Although it is mainly in the epistles of Paul that the work of the Holy Spirit and Christian behaviour are firmly linked, there is a drawing together of the two in the gospels, albeit in an indirect manner. Luke especially relates the Spirit, kingdom and prayer to decisive moments in the ministry of Jesus.24 In this connection it is interesting to note that the parable of the Good Samaritan (Lk. 10:25–37) is placed between the story of the sending of the 70 to announce the coming of the kingdom, in which Jesus rejoices ‘in the Spirit’, and Jesus’ teaching on prayer and the need to ask for the gift of the Holy Spirit. However, it is in the Gospel of John that the centrality of the Spirit in the Christian life is stressed. He is the one who will enable Christ’s followers to bear fruit and so glorify him (Jn. 14–16).

Central to any understanding of Jesus’ attitude towards ethics is a group of sayings that are to be found in Matthew 5:17–18, although originally they may have been independent of each other.25 First of all there is the statement: ‘Think not that I have come to abolish the law and the prophets; I have not come to abolish but to fulfil’. This is then followed by another statement reaffirming the abiding significance of the law: ‘For truly I say to you, till heaven and earth pass away, not an iota, not a dot will pass from the law until all is accomplished’.

It should be pointed out that the texts do not say anything about the law per se. A distinction is not made between ceremonial, moral or civil law, as some Christians do today; rather, Jesus is concerned with the law in its entirety. Clearly the key to the interpretation of these verses is to be found in the meanings of the verbs ‘abolish’ and ‘fulfil’.

In saying that he came not to abolish the law (katalusai = ‘nullify’—doubly stressed in v. 17), it could appear that Jesus is enjoining continual adherence to the law. However, Jesus goes on to say positively that he has come to ‘fulfil’ the law (plērōsai), and this verb suggests more than simple adherence. It is something which has to be understood from the standpoint of the whole of Jesus’ ministry, and the thought is not so much that Jesus came to keep the law right down to the last detail, but rather that he gives to the law and the prophets a deeper and richer understanding, expressing their inner intention and purpose; thus they are ‘fulfilled completely’. R. J. Banks summarizes the relation between Jesus and the law as follows: ‘It therefore becomes apparent that it is not so much Jesus’ stance towards the law that Matthew is concerned to depict: it is how the Law stands with regard to him, as the one who brings it to fulfilment and to whom all attention must now be directed.… The true solution lay in understanding “fulfilment” in terms of an affirmation of the whole law, yet only through its transformation into the teaching of Christ was there something new and unique in comparison.’26 Perhaps one should further add that it was also by the law’s realization in the life of Christ that something new and unique occurred.

Such an understanding would go a long way towards explaining Matthew’s concern for ‘righteousness’, with the noun dikaiosunē occurring some five times in the Sermon on the Mount. In the OT the primary meaning of ‘righteousness’ (Tsedeq) is that which meets with approval in the heavenly court. The man who is declared ‘righteous’ is the one who is pronounced as standing in a right relationship to God. As Steve Motyer has shown,27 this is intrinsically bound up with God’s salvific purposes in that he is concerned with establishing righteousness (doing and seen to be doing what is right) by acting on behalf of the outcast and the needy. It is in Christ that this is decisively achieved, the one in whom the will of God is realized, the covenant completely kept and through whom salvation has been wrought. The ethical implications for Christ’s followers then become clear: they too are to seek God’s kingdom and his righteousness—his rule and saving action—and are to reflect the same character of righteousness in their lives. It is by acting on behalf of those who cannot help themselves that they are to exceed the ‘righteousness of the Scribes and Pharisees’ (cf. Mt. 5:20; 25:31). Thus, far from the law and the prophets being dissolved by Christ, they are in fact completed and transcended by him. What is more, their inner intention, which is the outworking of God’s saving rule, is in turn to be recapitulated by members of the kingdom both individually and corporately.

One implication of such an interpretation is that for the Christian, OT ethics cannot be viewed in isolation of Christ who is their full expression and exposition. Love is the fulfilling of the law (Rom. 13:8), and in a deep sense Christ’s love did just that (thus he is the ‘end of the law’, Rom. 10:4). But what we see completed by him and in him is to be reworked in the lives of his followers. Although from the standpoint of OT exegesis one can consider the ethical precepts without reference to Christ, from the standpoint of trying to determine their application for the Christian such findings need to be ‘filled out’ by placing them in the light of Christ’s teaching and example.

A second implication of this position is that as law and grace become integrated under the over-arching concept of ‘righteousness’ fulfilled in Christ, Christian ethics proceed from the starting point of forgiveness and acceptance. This in fact is a pattern already established in the OT but which is often missed because of the Reformed preconception of law being prior to grace. It was after the event of the exodus, itself an act of grace, that the law was given. Indeed one may see the giving of the law as an expression of grace, a means of drawing the covenant relationship into a state of maturity. Paul also works to the same pattern, the ethical exhortations following developed doctrine of the saving acts of God (cf. Gal. 5). Theologically this is in effect to reverse Matthew’s ordering of the Sermon on the Mount, placing the demand of 5:48 first, ‘Be perfect’, and the resolution of 5:17ff., ‘I came to fulfil’, last.

We now turn to the way Jesus handled the so-called ‘traditions of the elders’. Scholars have differed in their views as to whether the Sermon on the Mount was intended by Jesus or Matthew as in any sense a new law. It is certainly not a law-code of the sort found in the OT, e.g. in the Book of the Covenant (Ex. 20:21–21:23). John Robinson describes much of this material as ‘shocking injunctions’,28 designed to jolt a person out of moral complacency, enabling them to ‘see’ things in a new way and so respond in a manner which is appropriate to the coming of the kingdom of God. Dodd29 prefers to speak of them as ‘parables of the moral life’ disclosing to a person the sort of things which might be required of anyone who is a member of the kingdom. Both these descriptions have their validity, but one should be wary of reducing the moral force of Jesus’ sayings by over-generalization. What we see are a number of ‘rules’ quoted by Jesus, some of which are to be found in the OT, others being the ‘traditions’ of the elders, all of which have been treated in a legalistic and casuistic manner (e.g. Mt. 5:21–48). On each issue—swearing, adultery, divorce, etc.—Jesus goes back to some underlying principle of truth which is concretely expressed as an imperative. Far from weakening the requirements of the law, Jesus’ treatment gives them greater force and a wider field of application, going well beyond the restraints of legalism. According to Dick France, the effect is ‘to make a far more searching ethical demand. In all of this, there is a sovereign freedom in Jesus’ willingness to penetrate to the true will of God which lies behind the law’s regulations.’30

It is this internalization of the law which underscores the point made earlier that ethics also embrace attitudes (Mt. 5:21f.). Of course this is not to imply that ‘thought’ and ‘deed’ are to be given equal moral weighting, so that ‘one might as well be hung for a sheep as a goat’. It does mean that when speaking of moral action, one must give the concept of ‘action’ a much wider interpretation than the mere physical act and its consequences. In considering the moral value of a particular action three constituent elements should be evaluated: intentions, consequences and event.

To take intentions first. As far as one is able, one should try and assess whether they are good rather than selfish. The problem of course is that there is usually a mixture of motives, desires and intentions; some are good, others less so. Invariably our ‘wants’ also contaminate to some degree our understanding of what is right, creating a distorted ‘moral vision’. However, there are instances where a sharp dichotomy does exist between what we want (e.g. to preserve our life) and what we should do (rescue the drowning man). One of the errors of situationism as advocated by Joseph Fletcher31 is that too much weight is given to intentions, such that if a person is convinced that his intentions are right, the act becomes morally acceptable. But this is too individualistic, and while psychologically securing a person from blame, does not ensure that an action is morally right. This is why intentions need to be taken together with the other two components of moral action as well as the moral imperatives which stand over and above the situation.

While situationism gives a prominent place to intentions, it is utilitarianism which gives pride of place to consequences. But this too proves to be an inadequate criterion for determining the ‘rightness’ of a course of action. To say that one should take the course which promotes the ‘greatest happiness for the greatest number’ begs the question of what constitutes ‘happiness’. This is far too general a concept to be of any use. What is more, it requires that the moral agent should be in a position to determine what consequences his action will bring. But this again is asking too much, for we are all painfully aware of the many unwanted effects that our ‘well-intentioned’ actions have thrown up in the past. Finally, this position fails to take into account the complex relationship between events and consequences. To speak of an action as ‘a means to an end’ is in itself an abstraction, for that ‘means’ is an ‘end’ of an earlier ‘means’. The web of cause and effect is far more mysterious than this position allows for. However, possible consequences do have to be taken into account as we wrestle with the options open to us in a moral situation, and the Christian will also be humbled by the fact that consequences of eternal significance have to be placed in the balance.32

In addition to intentions and consequences, the act itself will need to be taken into the reckoning. It is questionable whether one can legitimately speak of ‘an act-in-itself’, as if the act could be divorced from its wider context of intentions and consequences. However, one may make a working distinction (rather than a formal one) between an ‘event’—which is neutral in description, and an ‘action’—which is related to intentions and consequences. Such a distinction might enable one to discern more effectively the moral relevance of a factor which can easily be overlooked while solely operating with the notion of ‘moral action’. For example, on the basis of intention and consequence a case could be made for sex outside of marriage (intention = I wish to share my love with my partner; consequence = no unwanted pregnancy due to contraception and we are happy). But if after considering the sex act as ‘event’ it is concluded that this in itself is expressive of promise and commitment, then this brings into question the morality of the situation, for what is being expressed by intercourse is denied by the overall situation, including the intentions of those involved. (A similar exposure of the disparity between actions, intentions and consequences is to be found in Jesus’ treatment of the tradition about ‘Corban’ in Mk. 7:5–13.)

As we have seen, Jesus’ approach to ethics is far more ‘open-ended’ than legalism. It is also deeper in that it takes into account motives and intentions, and wider in that a decisive eschatological perspective is envisaged. As we shall see later, it is this ‘dynamic’ interaction between principles, intentions, actions and consequences which form the heart of Christian moral decision-making.

Jesus and ethics—the example

In speaking of Jesus as ‘God incarnate’ (and thus the ‘Good’ incarnate), one is making a double point. The first is that it is God who does that which man cannot do and refuses to do, namely the fulfilling of the law and the perfect expression of the moral life. The second is that it is God as man in whom these things happen, thus what man ought to be actually is in Christ. As W. F. Lofthouse put it, ‘If we could tolerate the paradox, we might say that he was man because he was what no man had ever been before … Christ did not become what men were; he became what they were meant to be …’.33 Therefore, not only would the Christian wish to point to the teaching of Jesus to illuminate morality, but also to his acts as providing a model or paradigm for true moral behaviour. This is particularly important if one is to make use of the vast wealth of ethical material in the gospels which goes beyond specific moral teaching. This is especially true in a gospel such as John where, as John Robinson notes,34 very little moral teaching is given didactically, but a considerable amount is conveyed through action. Indeed this is the Johannine emphasis upon living as Jesus lived and not merely as he taught(Jn. 13:34; 1 Jn. 2:6; 3:16). For John, Jesus is the exemplar par excellence.

The concept of Jesus as moral paradigm also gathers up much of what was said earlier about the fulfilment of ‘righteousness’. As it is in Jesus that God’s righteousness is shown, especially in the cross where God declares himself both just (dikaion) and the justifier (dikaionta) of him who has faith (Rom. 3:26), we are given tremendous insight into what true righteousness means in action. This is well summarized by Motyer: ‘The basis of the whole life of the people of God is his righteousness—his outreaching, saving mercy which rescues creation for himself. This righteousness has now been supremely expressed in Christ. But as men are grasped by it, “justified” and made acceptable to God, so they are stamped with the image of the righteous Saviour, and summoned to live in imitation of him as his people.’35

Without doubt, as Luther stressed, it is possible to hold to a slavish literalism of the notion of ‘imitation of Christ’ so as to turn it into a new form of legalism, and yet one should beware of so overreacting to this danger that one robs it of any ethical content. It is an idea which is firmly embedded in the NT, with its roots grounded in the OT with Israel’s call by God to be ‘holy for I am holy’ (Lev. 11:44; 19:2; 20:26). Within the context of the master/slave relationship Peter writes: ‘Christ also suffered for you, leaving you an example [hypogrammon—to ‘trace’ or ‘copy’], that you should follow in his steps’ (1 Pet. 1:21). Here it is the cross which provides the primary reference point at which the imitation is to be followed (cf. Eph. 5:21ff.). The same focus is to be found elsewhere. On the question of humility it is the divine condescension which is appealed to (Phil. 2:5ff.), as it is in the case of charitable giving (2 Cor. 8:9). Certainly for Paul it was the realization that God had done something of such magnitude for the Christian in the life, death and resurrection of Jesus that provided the nerve cord for Christian morality—cf. Gal. 2:20ff.: ‘I have been crucified with Christ … it is no longer I that live but Christ … I live by faith in the Son of God who loved me and gave himself for me.’ In addition there is room for growth and development of the moral life, hence the call to ‘put on the mind of Christ’ (Eph. 5:23) and to ‘bear fruit’ (Gal. 5:22).

Rather than a detailed example to follow, Christ’s life, and the culmination of that life in his sacrificial death, provides a pattern to be copied. But it is at this point that a particular epistemological problem is raised and which can be formulated as follows: ‘To recognize a person as a good example to follow presupposes that one already has a set of moral criteria by which to judge the example, therefore one may ask what, if anything, does the example add to our understanding of morality? Is it not superfluous?’ It was Kant who put the problem in its starkest form: ‘Even the Holy One of the Gospels must first be compared with our ideal of moral perfection before we can recognize him as such’ (Grundlegung). However, the fallacy of this objection has been clearly set forth by Basil Mitchell.36

While agreeing that it is true that in order to recognize someone as a good example to follow we must have some notion of what ‘goodness’ is, Mitchell maintains that it does not follow that we should be able to describe in detail beforehand the actual features of a good example. He illustrates this point from the game of rugby. If a person recognizes Fred Smith to be a good rugby player, and thus a good example to imitate, then he must have some idea of the [game of rugby, the basic rules, the sort of moves involved, and so on. But this does not mean that the observer would be able to describe beforehand the moves Fred Smith was going to make. The rugby enthusiast has, as it were, a ‘form’ in his mind of the game ‘rugby’, and seeing Fred Smith in action gives new ‘content’ to that form. The same can be said when it comes to recognizing a moral example. Man having a moral J sense, as well as having specific moral content, can have that enriched as he looks to Christ, perceiving that here we do have an example to emulate. As Mitchell himself puts it: ‘It does not, fortunately, take a saint to recognize a saint, a I genius to recognize a genius, a master of a trade to recognize a master, a phronimos (wise man) to recognize a phronimos.’37

Jesus and ethics—relevance and application

It transpires from the discussion so far that within the context, of Christian ethics it is Christ who is the focus of morality, the synthesis of the ought and is. As with any moral fact (and the Christian would wish to add that here is the moral fact incarnate) there is the necessity of obligation. Certainly a distinction has to be made between someone recognizing something as a moral fact, which carries with it the notion of obligation, i.e. x is good therefore I ought to do x; and discussing whether something is a moral fact, in which case no decision has been made. Of course there is also the possibility that someone may recognize a moral fact and yet choose to ignore or reject it. This equally applies to Christ as ethical teacher and exemplar as to any principle or rule. Even so, if Jesus is the archetypal moral man, the Ideal, and is recognized as such, then this carries with it a sense of obligation that we too ought to imitate this pattern which, in turn, has to be translated into our own situation. But the question arises as to how this translation is to take place and to what extent the teachings and example of Jesus are binding.

So far it has been claimed that Jesus is the personification of the Good, the Universal which has been revealed in a specific historical-cultural situation. The fact that Jesus’ teaching was clothed in the language of his day, and that his lifestyle and mode of behaviour were appropriate to his contemporary culture, means that a certain amount of relativity is introduced into Jesus’ ethics. Indeed, this is a phenomenon which is inevitable with any use of language. The moment specific content is given to a principle it is also given a limited range of meaning relative to the culture and circumstances. Thus ‘Do not steal’ will create a certain ‘resonance’ in the minds of the people who hear that injunction, conditioned by the sort of things which constitute ‘stealing’ in their particular culture. However, the specific principle enunciated is still an articulation of something which is universal; it does not undergo a thorough relativizatoion. This also applies to the idea of Jesus as ‘example’. The pattern of humble service and sacrificial self-giving is expressed relative to Jesus’ specific historical circumstances, the universal pattern being given concrete expression so that we can ‘see’ what this pattern involves, rather than allowing it to remain at the level of general abstraction. Having considered the historical acts and attitudes of Jesus as they are worked out in the 1st century context, we then have to translate them into our own. This means that there will be discontinuity, due to the loss of that which is culturally relative (e.g.feet washing), but also continuity in that beneath the specific expression there is a universal quality or ‘core’ which can be transferred and applied regardless of time and culture. Keith Ward gives an example of how such a translation of the ‘imitation of Christ’ might apply to a Christian who is a scientist. He writes:‘… the man who feels that it is his vocation to pursue intellectual studies may allow the pursuit of truth to be the predominating value of his life; and in so doing he will not, of course, be ‘imitating Christ’ in any direct sense, since Christ was not a scientist. But, at the same time, an acknowledgement of the Christian ideal of life will temper the scientist’s attitude to his own vocation. It will prevent him from erecting an ideal of intellectual superiority, from despising the ignorant, and from supposing that the pursuit of truth is the only value which should be acknowledged by all men.’38

Allowing for both the universality of the life and sayings of Jesus for ethics and yet at the same time their relativity, what sort of process is involved in the moral decision-making which a Christian individual or community might engage in? What is offered below is one way of answering this question. In part it is descriptive in nature, formalizing the sort of approaches Christians often adopt in reaching moral decisions, but it is also prescriptive in suggesting a particular approach which builds upon some of the considerations outlined above.

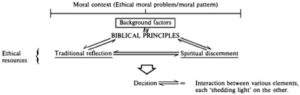

Taking the application of moral principles first. It is proposed that in considering a moral context, that is, either a particular moral problem to solve or a pattern of behaviour to follow, a dynamic interaction exists between the principles based upon Scripture and the overall situation. Thus one would need to take into account the various ‘background factors’ which make up the situation (e.g. what the needs are, the constraints of the situation, the ability of the moral agents, etc.) and in the light of these consider the relevant biblical principles. Identifying and interpreting the biblical principles is a supremely important task, since Scripture is the normative authority in Christian ethical decision-making. But attention should also be given to ‘moral tradition’, that is, other relevant ethical thinking which has been undertaken in the past. It is out of an interaction between these ethical resources and the actual situation under the guidance of the Holy Spirit that a moral decision is derived. This ‘moral dialectic’ can be summarized in diagrammatic form (see Fig. 1 on page 17).

Many moral situations are complex, and the interactionist approach as outlined above allows for such complexity. It applies universal moral principles which are grounded in Scripture and elucidated by the same hermeneutical procedure adopted by Christ, viz. pinpointing the underlying truth and principle beneath a moral injunction or story and reapplying it to present circumstances. It also takes seriously the particularity of the actual situation, thus avoiding bland generalizations, yet it refuses to allow circumstances wholly to determine the principles employed (as with situationism) because of the belief in absolute values and a recognition of a wider, eternal context. There is also a place for traditional moral reflection, drawing upon the wisdom of those in the Body of Christ (past and present) whom God has gifted in ethical thinking. But also, it incorporates a strong charismatic element, realizing that such a process is not a mere cerebral exercise, but an openness to the guiding hand of the Holy Spirit.

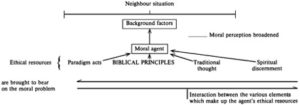

However, as it stands this process is incomplete, for a Christian would also want to appeal to the example of Christ himself. In coming to a decision about a particular moral situation, the Christian will not only take into account ethical principles but also patterns of behaviour, especially the pattern set forth by Christ. In other words various ‘paradigm acts’ (lived-out examples) which related to a specific moral problem will also be incorporated into the moral decision-making process. For example, supposing that we are faced with a situation where we are being asked to give advice on whether a friend’s unmarried daughter should have an abortion. This may be described as a ‘neighbour situation’—there is a moral need arising in the life of a neighbour (in the broadest sense) and the immediate requirement is advice. Initially, the moral agent will have an immediate perception of the moral difficulty, considering the various ‘background factors’ which comprise the needy situation (e.g. the girl’s age, the circumstances of the pregnancy, the attitudes of the girl and her parents, etc.), as well as having a primary moral response in being willing (hopefully) to listen and give appropriate advice, and having some ideas, however vague, on the issue in question. This primary stage can be represented as shown in Fig. 2, on page 17.

The one who has been sought for advice will then broaden and enrich his moral perception by drawing upon the ethical resources mentioned earlier. The biblical principles which will be determinative in our attitude will include the fifth commandment, ‘You shall not kill’, as endorsed by Jesus, and the whole biblical concern for the sanctity and quality of all human life. They will include also and supremely the importance of compassion, especially compassion for the weak and needy. It is at this point that the paradigm acts of Christ provide a focus for the moral agent in indicating what this compassion will involve. To be sure, the way Jesus approached needy situations will mean that two important qualities will be looked for. The first is that compassion be real, not sentimental, or a cover for some ulterior motive (e.g. seeking an abortion to get around the embarrassment of having to face one’s friends with an unwanted pregnancy). It is clear that Jesus’ compassion ran deep (cf. Mk. 1:41) and was far from superficial; indeed, it was sacrificial. Furthermore, not only is this compassion to be real, it also has to be radical; not necessarily going for the ‘easy option’, which may not deal with the root of the predicament at all. Jesus had compassion for the rich young ruler, but its radical nature meant that it would not compromise with half-baked ‘immediate’ solutions (Mk. 10:17ff.). A further part of the process will be the evaluation of other people’s thinking on the moral question in hand, this taking place within the wider context of the church as the Body of Christ, and under the prayerful guidance of the Holy Spirit (see Fig. 3 on page 17).

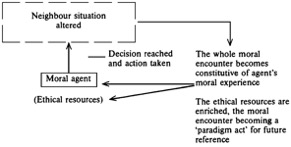

Arising out of this moral dialectic, a decision is reached and informed advice may be given. However, it should be stressed that although the primary objective in the situation envisaged above was to give advice, clearly the moral process is much wider, calling upon the moral agent to realize in practice the second great commandment to ‘love your neighbour as yourself’. This will mean extending a loving heart, and engaging in sacrificial empathy where required as well as offering wise words. Furthermore, the whole moral encounter should extend the moral repertoire of the agent and itself become a moral paradigm for future reference (see Fig. 4 on page 17).

The extent to which the above model will be both acceptable and applicable will largely be determined by a person’s stance viz-à-viz the Christian faith and biblical authority. If a person places himself firmly within the Christian fold, appeal to the Bible, tradition and the illumination of the Spirit will be both natural and acceptable. But what of the person who would place himself squarely outside Christianity? To what extent will the ethical teaching and example of Jesus be binding upon him?

Two preliminary points need to be made in this regard. The first is that the moral authority of Jesus is integrally related to his person—the ‘What’ is decisively linked to the ‘Who’. That is, what Jesus says is both determined by who he is (the eternal Son of God) as well as being evidence of who he is. This is clearly brought out by Jesus’ distinctive form of address, prefacing his words with ‘amen’, thus identifying God in advance with what he is about to say (Mt. 5:18, 26; 6:2; etc.). In addition to the fact that Jesus did not appeal to the ‘traditions’, this will account for the astonished reaction of the crowds as recorded in Matthew 7:28: ‘When Jesus had finished saying these things, the crowds were amazed at his teaching, because he taught as one who had authority, and not as their teachers of the law’. But what is more, the authoritative pronouncements of Christ were of a piece with his actions. Not only did Jesus declare forgiveness of sins, he authenticated his words by healing (e.g. Mk. 2:1–12), both word and deed thus being expressive of his being as unique bearer of the divine nature. The moral authority of Jesus is therefore both unique and supreme because it is not derived ‘second-hand’ but is proclaimed directly, stamped with the very authority of God.

The second point is that strictly speaking Christian ethics is for Christians, those who acknowledge the Lordship of Christ, who are members of the kingdom and who are empowered by the Spirit to bring about a substantial realization of that kingdom in their lives. There is considerable weight behind the contention that the Sermon on the Mount is directed to those who are already, or potentially, followers of Christ (cf. Mt. 5:1b, 2—it is the disciples who are addressed).

Even so, these two considerations do not carry the corollary that Jesus’ teachings and life only have moral force for those allied to the cause of the kingdom. In both principle and practice this is clearly not the case. If, as has already been argued, morality is both objective and universal, part of the warp and woof of reality, then in principle it should be possible for such universals to be recognized, together with their binding nature, regardless of their source or the particular framework of beliefs held by the observer. This means that whether the source be Christ or Socrates, provided that it is to the true nature of moral reality they refer, acknowledgement should be possible by the person who in general does not subscribe either to the Christian faith or the philosophy of Socrates. To adapt Mitchell’s example of the rugby player, it should be possible to recognize Fred Smith as a good rugby player even if one is not a supporter of his team or an active player oneself.

But not only is it possible in principle for those outside the Christian faith to recognize the validity of Jesus’ ethical teaching, it is also the case in practice. It appears that Gandhi was able to accept much of Jesus’ ethic, but not other elements of his teaching. One of the great dangers of 19th-century liberal theology was the reduction of theology to mere morality, with Christ being presented simply and solely as the Ideal Man pointing the way to the authentic moral life. This was a movement whose roots lay in Kant’s contention that Jesus was the ‘personified idea of the good principle’. However, given that Jesus is at the very least the focus of the Good (although much more than that), then it is eminently reasonable to expect that some perception of that ‘Good’ should occur on a universal scale. While it is true that one may wish to question the logical consistency (or lack of it) of those who would want to take on board the moral claims of Jesus while rejecting his religious claims, one is still left with the fact that those moral claims are recognized well beyond the bounds of the redeemed community; indeed such a recognition may be but the first step of a journey towards the full acceptance of the Lordship of Christ.39

Concluding remarks—creation ethics and kingdom ethics

At first sight, it might appear that a firm and irrevocable division has been made between creation ethics and kingdom ethics, but this is more apparent than real and dissolves under close analysis. We should be wary of stressing the discontinuity between creation and kingdom ethics at the expense of the continuity. The point of continuity is that God is the author, and relationships the subject, of both ethics as they are grounded in the loving grace (hesed) of God. The line of discontinuity is drawn around the fact that it is in Jesus Christ as representative Man that God’s requirements of righteousness are met, a new covenant established, and relationships transformed by the eschatological Spirit which he dispenses. Indeed, it is Christ’s redemptive work which provides the proper vantage point from which to view God’s purposes in creation.

Even within the perspective of the OT, any attempt to separate off creation ethics from the wider context of redemption is doomed to failure. As Von Rad has shown,40 not only are Israel’s beliefs about creation inseparable from her beliefs about redemption, in many respects they are secondary. Therefore Chris Wright is quite correct in maintaining that: ‘At every point this creation theology was linked to the fact that the Creator God was also their, Israel’s, Redeemer God. This means that the “creation ordinances” can only be fully understood and appreciated when they are illumined by the light of Israel’s redemptive faith and traditions, and not merely taken as “universal” and somewhat abstract propositions’.41 If the word ‘Christian’ were to be substituted for the term ‘Israel’ in Wright’s statement, then it would provide a succinct summary of what is being maintained here, namely that it is in the light of the NT, and especially of Christ’s teaching and example, that OT ethics can be appreciated and appropriated.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2, stage A

Fig. 3, stage B

Fig. 4, Stage C: Action taken (individual or corporate)

However, it is when a Christocentric approach is adopted, one which is on line with the NT’s varied testimony that Christ is the integration point of all the works and purposes of God, that any hard-and-fast distinction between creation ethics and kingdom ethics has to give way to a more unified concept. We have already seen how Christ fulfils the inner intention of the law and the prophets; but it could equally be claimed that he also fulfils the inner purpose of creation as he brings about God’s kingdom—viz. that the Creator and creature should live in harmony (the goal of covenant). For in Jesus, God’s will is done, the kingdom has come and the Father’s name is hallowed. But furthermore, what was achieved in the life, death and resurrection of this one Man, Jesus, will be universalized at the end of time, as the whole of creation becomes caught up in God’s creative-redeeming action through this same person (cf. Rom. 5:21ff.; 8:18ff.). Or to put it another way, in Jesus there is an actualization of man’s true potential as God intended (God’s image); the ought becomes an historical reality. At the end of time the same image will be realized in other men, of whom Christ is the first fruits (1 Cor. 15:23). It is then that creation will be brought to true completion. The unity between creation and kingdom as found in Christ can be represented in Fig. 5 at the bottom of this page.

This same emphasis upon the unitary activity of God uniting both the work and goal of creation and the kingdom is to be found in Barth.42 He draws attention to what he sees as the conditio sine qua non of Christian ethics, the command and will of God, who in Jesus Christ is man’s Creator, Reconciler and Redeemer. What we perceive as three successive moments in God’s activity (Creation, Reconciliation, Redemption, to use Barth’s own terminology) are in reality one in the eternal movement of God (Creation-Reconciliation-Redemption). Thus from the overall standpoint of the God who ‘sees the end from the beginning’, any attempt to draw a division between creation/kingdom in absolute terms would be as erroneous as attempting to divide the Godhead.

The drawing together of creation and the kingdom to such a point that they more or less overlap is to be found in Colossians 1:15ff. In this great ‘hymn’ to the supremacy of Christ, Jesus is portrayed as the one by whom and for whom all things were created (v. 15). This is paralleled by the fact that he is also the one in whom and by whom all things are reconciled, establishing God’s rule (kingdom) throughout the created order (vv. 18–20). It follows that if the creation/kingdom division is finally overcome in Christ, then so is the creation/kingdom ethics divide, with the latter being the transposition of the former. The Colossian hymn is shot through with praise to the Creator-Redeemer Christ, and it is as his pattern and teaching is worked out in the lives of his people, the members of his kingdom, that the same song will be heard—the song of the priority of Jesus.

Fig. 5

1 John Wimber, Power Evangelism. Signs and Wonders Today (Hodder & Stoughton, 1985), p. 70.

2 This is almost turning the Ignatius method of Bible study on its head. This method invites the reader to think himself into the biblical passage and so engage in an ‘encounter’ with Christ. To attempt to ‘do what Christ would do’ by the imagination is to try and envisage Christ stepping out of the text into our situation. In both cases hermeneutical controls are singularly absent.

3 Os Guiness, Doubt. Faith in Two Minds (Lion, 1976), p. 91.

4 Cf. D.E. Nineham, New Testament Interpretation in an Historical Age (Athlone Press, 1976). For a critique of Nineham’s views see Anthony Thiselton, The Two Horizons (Paternoster, 1980), pp. 52–56.

5 I. H. Marshall, Biblical Inspiration (Hodder, 1982), pp. 99–113.

6 David Cook, in The Moral Maze (SPCK, 1983), includes ‘natural law’ under the category of creation ethics, but he uses the term in a much broader sense, consonant with what is being suggested here, avoiding the excessive claims associated with strict natural law theory.

7 D. Brown, Choices (Blackwells, Oxford, 1983), pp. 28–35.

8 G. E. Moore, Principia Ethica (Cambridge, 1903), chapters ii, iii and iv.

9 Cf. Greg Forster’s Cultural Patterns and Moral Laws (Grove, 1977).

10 Cf. C. S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man (Fount, London, 1978), p. 48.

11 Paul Ramsey, Basic Christian Ethics.

12 Some, like Don Cupitt, argue that ethics have to be autonomous and must be severed from religion for man ‘come of age’; for a reply see Keith Ward, Holding Fast to God (SPCK, 1982), pp. 50–62.

13 Cf. V. White, Honest to Goodness (Grove, 1981) and O. Barclay, ‘The Nature of Christian Morality’, in Law, Morality and the Bible (IVP, 1978).

14 Op. cit., pp. 33–34.

15 Op. cit., pp. 21–22.

16 Keith Ward, Ethics and Christianity (Allen and Unwin, London, 1970). pp. 89ff.

17 R. E. Clements, Old Testament Theology—A Fresh Approach (Marshalls, 1978), p. 96.

18 Baelz himself prefers to avoid the term ‘objective’ in relation to morals because of misunderstandings which could arise when placed in opposition to ‘subjective’, itself an emotive term. Hence his preference for the term ‘logical impartiality’—Ethics and Belief (Sheldon Press, 1977).

19 K. Ward, The Divine Image (SPCK, 1976), p. 41.

20 A point made forcefully and with his usual lucidity by C. S. Lewis in his essay ‘Man or Rabbit’ (God in the Dock, Fount, 1979, pp. 68–69), who in contrasting the beliefs of a materialist with those of a Christian shows how those differences will inevitably manifest themselves at the most practical levels of social policy.

21 Cf. A. N. Wilder, Eschatology and the Ethics of the Kingdom (New York, Harper Bros, 1950).

22 A. Schweitzer, The Mystery of the Kingdom (Black, London, 1914).

23 Cf. H. Thielicke, Theological Ethics (Fortress, 1966), pp. 648–667.

24 An observation made by S. S. Smalley, ‘Spirit, Kingdom and Prayer in Luke-Acts’, Novt 15 (1973).

25 James Dunn, Unity and Diversity in the New Testament (SCM, 1977), p. 246.

26 R. J. Banks, Jesus and the Law in the Synoptic Tradition (SNTS Monograph 28, CUP, 1975), pp. 226, 234.

27 S. Motyer, ‘Righteousness by Faith in the NT’, in Here we Stand, ed. J. Packer (Hodder, 1986), p. 35.

28 J. A. T. Robinson, The Priority of John (SCM, 1985), p. 322.

29 C. H. Dodd, Gospel and Law (Cambridge, 1951).

30 R. T. France, Matthew (IVP, 1986), p. 50.

31 J. Fletcher, Situation Ethics (SCM, 1966).

32 Cf. Mt. 5:27ff. gives the negative eternal consequences of failing to take the ‘right’ course of action and Mt. 6:1ff. the positive eternal consequences of true righteousness.

33 W. F. Lofthouse, The Father and the Son (London, 1934), quoted by Pollard in Fullness of Humanity(Sheffield, 1982), p. 86.

34 Op. cit., p. 336.

35 Op. cit., p. 53.

36 B. Mitchell, Morality. Religious and Secular (Oxford, 1980), pp. 147–150.

37 Ibid., p. 149.

38 Ethics and Christianity, p. 146.

39 Cf. White, op. cit.

40 G. Von Rad, ‘The Theological Problem of the OT Doctrine of Creation’, in The Problem of the Hexateuch and other essays (Oliver & Boyd, 1966), pp. 131–143.

41 Chris Wright, ‘Ethics and the OT’, in Third Way Vol. 1 No. 9 (1977), pp. 7–9.

42 Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics III, 4 (T. & T. Clark, 1961, pp. 24–31).

Melvin Tinker

The Reverend Melvin Tinker is senior minister of St John, Newland, Hull, UK. He has contributed a number of articles to Themelios over the years and is the author of several books, his latest being Intended for Good: The Providence of God (IVP, 2012).