Volume 45 - Issue 3

Deep Motivation in Theological Education

By Jonathan D. WorthingtonAbstract

“How can I motivate my students more?” In theological education, as in all education, students will gain the most from our classes and programs if they are deeply motivated and therefore engaged. So, the question of motivation is not minor. But the quantitative aspect of the question above—motivate them more—is actually not quite right. Rather, “Are we helping our students be motivated in the best way?” This article explores the basic difference between “intrinsic motivation” and “extrinsic motivation.” Most scholars of education think intrinsic motivation is the most potent for deep learning. It is potent, and important for theological education. But there are actually four types of extrinsic motivation, the final of which is just as deep and potent and essential for transformative theological education as anything. This article lays a theoretical foundation and a few practical ideas toward subsequent crucial practical experiments and suggestions for transformative theological education.

“How can I motivate my students more?” This is a noble ambition, though it is not on the radar of many professors. They focus on how to express something accurately, perhaps even clearly. It will be a new idea to many teachers that they may have a responsibility, or at least an opportunity, to aid a student’s motivation. Some will jump at the opportunity: “Yes, I want to motivate them more. But how?”

In theological education, as in all education, students will gain the most from our classes and programs if they are deeply engaged. So, the question of motivation is not minor. But the quantitative aspect of the question above—motivate them more—is actually not quite right. Rather, “Are we helping our students be motivated in the best way?”

You have likely heard the catch phrase, “Practice makes perfect.” But what if you are practicing wrong? A tennis player who practices a badly formed serve more and more will actually be harder to help shift to a healthy swing. As my father taught me (borrowed from Vince Lombardi), the truth is that perfect practice makes perfect. The type, the way, the quality matters profoundly. It is similar in education. If you help your students be motivated more, but with the wrong kind of motivation, you may actually be shooting them in the feet as they try to walk the path of growth.

This article on deep motivation nestles into a global movement in higher education that seeks “transformational education.”1 Transformation is at the heart of education.2 God’s Spirit transforms, creating life where there is none, shaping dust into beautiful vessels. Yet the Potter has molded humans so that psycho-social motivation is close to the heart of how he transforms people. And within human learning, God has not designed all types of motivation to be equal.

1. Basic Types of Motivation: Intrinsic and Extrinsic

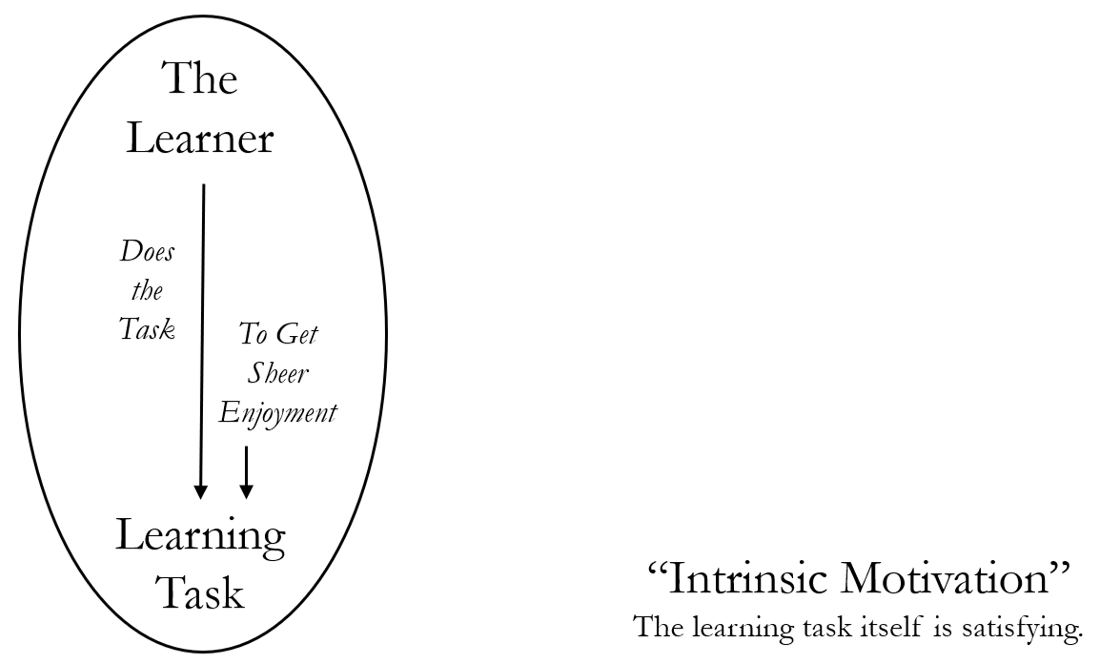

There is an important qualitative distinction within motivation: extrinsic vs. intrinsic. (See Figures 1 and 2 below.) The fundamental division point within education is enjoyment and satisfaction in a learning-task in and of itself. There are additional crucial factors, as we will see below, but this is the most basic divide. My working definitions of these two types of motivation are as follows.3

Intrinsic motivation: A given task is an end in and of itself.

Enjoyment of the task per se is what motivates the student. The motivation to do the task is intrinsic to the learner-and-task relationship.

Extrinsic motivation: A given task is performed as a means to an end.

The end, rather than enjoyment of the task itself, is what motivates the student to perform the task. The motivation to do the task is extrinsic to the learner-and-task relationship.

Notice what “intrinsic” and “extrinsic” mean and do not mean within motivation theory. As I have taught motivation theory, this is the typical first point of confusion. The terms are not synonymous with “within the person” versus “outside of the person.” The difference between intrinsic and extrinsic motivations are about the relationship between the task and the actor, not about the internal psychological experience of the actor himself. That is, something will be going on inside the actor’s psyche in both types of motivation, so to equate intrinsic motivation with an internal experience over against extrinsic motivation as something that is merely outside the actor will start us on a poor trajectory from the very beginning and create problems later. We will return to this. See Figures 1 and 2 below.

According to proponents of intrinsic motivation in learning, the sense of enjoyment, of “intrinsic task interest,”4 is the heart of genuine, deep, perpetual learning.5 Without enjoyment of the learning task, they suggest, the student will not keep at it in a meaningful way, for it will not have sunk deeply into both aspects of their long-term memory, explicit and implicit.6 Task enjoyment “enhances the attention, effort, and learning one directs toward that activity.”7 By contrast, extrinsic motivation means that something other than the learning task motivates the learner to do it—i.e., something external to the relationship between learner and task. The task per se is not enjoyable or satisfying. It is the means to a different end.

Most people think of extrinsic motivation as the carrot versus stick technique. An assignment is given. A reward (an A) or punishment (an F) is promised. A student does the assignment to get the grade and pass and graduate. The problem with extrinsic motivation, some say, is that “there is no direct relationship between extrinsic motivation and the desired behavior except the sought-after reward.”8 Neither the carrot, which is the promised reward for good work, nor the stick, which is the threatened punishment for bad work, is truly effective, for they will never “help create the conditions that encourage and inspire others to motivate themselves and achieve optimal performance.”9 What exactly is the natural relationship between, for example, exegeting Exodus 12 or 1 Corinthians 7 and an A grade? Is there anything about being motivated by an A and away from a C or F that, in itself, actually equips the student to exegete better? Granting grades of quality after the fact is one thing; using those as motivations to perform the task itself is quite another.

On the other hand, scholars observe that intrinsically motivated people “learn for its own sake”10 and do an activity “for inherent satisfaction or pleasure” as if the activity “is reinforcing in-and-of itself.”11 Because their motivation is naturally and immediately linked to the task itself, they are thereby “more likely to plumb the depths of understanding.”12

2. Deeply Transformative Intrinsic Motivation

Intrinsic motivation—enjoyment and satisfaction with the learning task per se—is often connected to maintained satisfaction13 and good quality production.14 High-quality conceptual understanding, creativity in their thinking, and persistence in the overall task of learning are each significantly enhanced by intrinsic motivation.15 High intrinsic motivation “promotes flexibility in one’s way of thinking, active information processing, and tendency to learn in a way that is conceptual rather than rote.”16 These qualities sound important for the tasks involved in transformational theological education!

The descriptions above of intrinsic motivation and its benefits compare well with the descriptions of deep learning rather than surface learning by Graham Gibbs (see Figure 3).17

| (1) Surface: Learning as an Increase in Knowledge “The student will often see learning as something done to them by teachers rather than as something they do to, or for, themselves.” |

| (2) Surface (Deeper): Learning as Memorizing “The student has an active role in memorizing, but the information being memorized is not transformed in any way.” |

| (3) Surface (Deeper): Learning as Acquiring Facts or Procedures to Be Used “What you learn is seen to include skills, algorithms, formulae which you apply etc which you will need in order to do things at a later date, but there is still no transformation of what is learnt by the learner.” |

| (4) Deep(er): Learning as Making Sense “The student makes active attempts to abstract meaning in the process of learning. This may only involve academic tasks.” |

| (5) Deep(est): Learning as Understanding Reality “Learning enables you to perceive the world differently. This has also been termed ‘personally meaningful learning.’” |

Intrinsic motivation can powerfully aid a student in shifting from shallow, surface learning to deep, creative, meaningful, and transformative learning.

When I began teaching, I thought about motivation as merely “intensity level”—the students having more or less.18 But motivation is about kind as well as level, about quality as well as quantity. My understanding was ill-equipped to effectively help students be motivated in a targeted and powerful manner toward deeper, more creative, and more robust biblical and theological learning. I was toying with tabbies instead of stirring up a tiger.

It is hopefully clear that our question should be “How can we motivate our students in a way that is conducive to deep learning?” I have already guided you on two steps toward a healthy answer. I described the healthy first step in motivating our students in a better way: recognize the basic distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (§١). I then described the healthy second step: see how intrinsic motivation is a powerful tool in theological education (§٢). But there is more, for a shallow exploration of extrinsic motivation has given it a bad rap in deep and transformational learning. There are different levels of extrinsic motivation (§3), and the deepest is profound and powerful (§4).

3. Exploring Types of Extrinsic Motivation

For those who know the basic distinction described above between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, it is popular to champion intrinsic over extrinsic—as if intrinsic motivation claims the lion’s share of raw power for deep learning. We see evidence of this perspective in many of the quotations above. Truly, intrinsic motivation is very effective for deep learning. But it is a mistake to downplay the importance of extrinsic motivation for deep learning—particularly certain levels of extrinsic motivation.

Extrinsic motivation itself has four different levels.19 When the task per se is not inherently enjoyable or satisfying, what might “regulate” a student’s engagement in the learning task? (See the chart in figure 4 below.) The first level of extrinsic motivation is actually effective and good, but for shallow and relatively straight-forward learning. The second and third plumb deeper in important ways. The fourth level of extrinsic motivation is actually excellent for deep and creative learning; in fact, it is just as potent as intrinsic motivation.

3.1. Reward and Punishment (Extrinsic Motivation Level 1)

A student wants to carry out the learning task in order to get an external reward (e.g., a good grade) or avoid an external punishment (e.g., a fail). He thinks, “What I want is the reward, and I don’t want the fail; I’ll learn the thing.” His motivation to learn X is regulated by gains that are extrinsic to the learner-task relationship as well as totally external to the learner himself. The literature calls this form of extrinsic motivation “external regulation.” I will call it “Reward and Punishment” to capture its heart. This is the type of motivation that many people think of when they contrast extrinsic as impotent (like a housecat) with intrinsic as potent (like a tiger). But this is only the first, shallowest level of extrinsic motivation. (See more in §4.1 below.) Keep searching; a lion of motivation is still at large.

3.2. Obligation Borrowed (Extrinsic Motivation Level 2)

A student is told he should complete the learning task, that it is important. He injects into himself the teacher’s “should” in such a way that he now really does want to do it, but only so as to feel pride or avoid feeling guilt. He reasons (perhaps unconsciously), “You say this is important to do? Okay, it’s important; I’ll do it.” The literature calls this form of extrinsic motivation “introjected regulation.”20 I will call this level “Obligation Borrowed” to capture its heart. The student’s motivation to learn X is regulated by something external to the learner-task relationship. It is borrowed from outside that relationship, though being introjected it is therefore a little more internalized, and thus a little deeper than the purely external regulation at Level 1.

3.3. Abstract Importance (Extrinsic Motivation Level 3)

A student is told that a certain learning task demonstrates or aids in acquiring a certain value or quality, such as the responsibility to handle the poetic aspects of God’s word well. Since the student identifies with the abstract principle that such a responsibility is good and valuable, he wants to do the learning task. He reasons, “Yes, this task matches what I also think this is important. I’ll do it.” He is not motivated by some disconnected and purely external offering (Level 1). He also does not merely unconsciously borrow and introject someone else’s (the teacher’s) ought (Level 2). Rather, the importance and benefit of the learning task resonates with his own value system. His motivation to learn X is “regulated” by something he already identifies as valuable, even though only as an abstract principle. This form of extrinsic motivation is thereby more internalized and deeper still than either Reward and Punishment (Level 1) or Obligation Borrowed (Level 2). It is still “extrinsic” to the task-and-doer relationship, for it is not the enjoyment or satisfaction of doing the learning task itself that motivates the learner. The literature calls this third level of extrinsic motivation “identified regulation.” I will call it “Abstract Importance” to capture its heart. This relevance of a learning opportunity for a present but abstract value system is potent for deep learning. Though the lion is next.

3.4. Relevance for Identity (Extrinsic Motivation Level 4)

A student is told the learning task demonstrates or aids in acquiring a certain value or quality, such as the responsibility to handle poetry in God’s word well. (This is like Level 3 above, at this point.) But he does not merely think that this responsibility is valuable, in the somewhat abstract sense of Level 3 above. He believes that such a responsibility regarding Scripture is part of his very character and identity—who he is—so he wants to do the task. Perhaps he believes that honoring God and his ways is non-negotiable for himself as a human and Christian, and that handling God’s word with careful attention to the way God inspired it is necessary for honoring God appropriately. He reasons, “I must learn this if I am to be who I am supposed to be. I’ll do it.” The literature calls this form of extrinsic motivation “integrated regulation” since the motivation is integrated into the very fabric of the student’s self-identity. I will call this deepest level “Relevance for Identity” to capture its heart. Even though he still does not enjoy the learning task per se, and so his motivation to engage it is still extrinsic to the student-task relationship, his motivation to learn X is “regulated” by something fully integrated into his personhood, his sense of identity. This form of relevance for personal and communal identity is the most potent form of extrinsic motivation and powerfully feeds the deepest, most lasting, and transformative learning.

Abstract Importance (Level 3) and Relevance for Identity (Level 4) are both essentially about relevance. Does the student “identify” with the relevance of the task, even if abstractly so? Abstract Importance is deep extrinsic motivation: “I can see that this is relevant to principles I value; therefore, it is important. I want to do it.” But the relevance is still relatively abstract, about held principles. This shifts when the relevance of the task is fully “integrated” in the student’s self-perception. Relevance for Identity is very deep extrinsic motivation: “This is so relevant for my own identity that it is essential. I really want to—indeed I must—do it or I will not be who I was created, saved, and called to be!” The student still may not find it enjoyable. But the identity-formation and the learning task are so naturally and intimately connected that the student is now deeply motivated and even equipped to perform the learning task. It will transform him. And it will enable him to transform others.

| Intrinsic Motivation The task is the end itself. It is done because it is enjoyable and satisfying. |

A student wants to do a learning task because he finds it satisfying and enjoyable in itself. “This is enjoyable and satisfying. I’ll do it.” |

Deep Motivation (deep learning) |

|

|

Extrinsic Motivation The task is a means to an end. It is done not out of enjoyment itself but because it will lead to something else that is deemed desirable. |

Rewards and Punishments (External Regulation) |

A student wants to do the learning task for an external reward (e.g. a good grade) or lack of punishment (e.g. no fail). “I want to get the reward. I’ll do it.” |

Shallow Motivation (shallow learning) ↓ |

|

Obligation Borrowed (Introjected Regulation) |

A student is told he should do the learning task. He borrows the “should” in such a way that he wants to do it to feel pride or avoid feeling guilt. “You say I should do it? Okay, I’ll do it.” |

(deeper motivation) ↓ |

|

|

Abstract Importance (Identified Regulation) |

A student is told the learning task shows, e.g., responsibility. Since he identifies with the principle that responsibility is good, he wants to do the task. “Yes, I do see this is important. I’ll do it.” |

(deeper learning) ↓ |

|

|

Relevance for Identity (Integrated Regulation) |

A student is told the learning task shows, e.g., responsibility. Since he believes responsibility is part of his character—who he is—he wants to do the task. “This is important for who I am. I’ll do it.” |

Deep Motivation (deep learning) |

|

4. Deeply Transformative Extrinsic Motivation

I have briefly outlined the four basic types of extrinsic motivation (§3). Let us now compare some of them in more detail, particularly the shallowest level of extrinsic motivation (Reward and Punishment, “external regulation”) with the deepest level of extrinsic motivation (Relevance for Identity, “integrated regulation”). The nuances will help us understand our students more fully and enable us to creatively contemplate our practice in the classroom.

4.1. Exploring Shallow Extrinsic Motivation—Reward and Punishment

A common type of motivation used by teachers and professors is Reward and Punishment, or “external regulation,” the shallowest form of extrinsic motivation. In some ways, most educational systems lend themselves to this. The teacher presents a reward—a carrot, a good grade, a degree—or a punishment—a stick, a bad grade, a fail—as motivation to participate in learning tasks. The students are motivated to learn X, not because they enjoy X (intrinsically), nor because they care about X (either as Obligation Borrowed or as Abstract Importance), and certainly not because they feel they must do X so as to be who they understand they are created, saved, and called to be (Relevance for Identity). They are motivated to learn X because they want the good grade and the degree, and they don’t want the bad grade or the fail.

Students ask, “Will this be on the exam?” Their subtext is, “Do I need to learn this to get a good grade? Because if it won’t help me pass, then I won’t waste my time learning it.” Professors say, “If you want an A on this essay, you need to do X, Y, and Z.” It is helpful to make expectations clear, of course; but if such statements are the professor’s majority approach to motivation, they subtly embed student motivation in the shallowest realm of reward and punishment. It becomes the pattern in which the majority of the professor’s students function and the default source from which they seek motivation.

Because of the type of motivation used—Reward and Punishment—the student may be able to perform X quickly. He may even be able to perform X “well”—i.e., getting a good grade. However, because he craves the carrot or despises the stick without (1) caring about X itself (intrinsic, the tiger of motivation) or (2) caring about how his character or identity would be shaped by learning X (deep extrinsic, the lion of motivation), his learning of X will not actually sink into him deeply. He is being nudged along by that tabby cat rubbing his leg. Neither the learning nor the motivation will stick with him over the long haul. He will not persevere in the learning when it is difficult. The carrot and stick will certainly not help him be transformed by his learning and enable him to transform others by it, for he does not find it enjoyable or relevant.

But it is not just that shallow extrinsic motivation is weak compared to deep extrinsic and intrinsic motivations. Quality is an issue here too. Do you want your students to learn or do something that inherently involves critical thinking and creativity?21 The type of motivation matters again.

Education in general can have a transformative and moral aim, helping shape students into global citizens who are better able to produce health in and through their respective fields. Charles Kivunja points out that a crucial aspect of this transformation in any field involves gaining “skills in critical thinking, problem solving, creativity and innovation,” and that one important task of an educator is to “provide for the training of students to gain mastery” in these skills and patterns.22 For theological education, wise living, biblical interpretation, theological thinking, and expositional and pastoral communication all involve creativity—they tend to be more art than science. However, when students arrive for a theology degree, “criticality” is not on many of their radars, and certainly not to the degree of importance that it is for their soon-to-be professors.23 Students tend to consider the education they are about to undergo as having their knowledge quantitatively expanded; professors tend to want students’ knowledge qualitatively deepened as well. The latter involves learning to critically engage primary and secondary material and to creatively solve problems.

But the carrot or stick form of motivation can actually undercut such learning aims. Not all types of motivation aid flexible, creative, and critical thinking. In particular, totally external motivators such as grades in education and monetary bonuses in a work-place actually appear to cripple creativity.24 Carrots and sticks put blinders on a thinker, narrowing his view to accomplish the task. This helps him “get the job done.” And this can be good—depending on what type of job it is. But when the “job” requires thinking “outside the box,” such shallow incentives streamline the sight and thereby block from view anything beyond the blinders, anything outside the box.25 But how much of the work of biblical scholars, students, or pastors is neatly contained in a box? The popular version of motivation is not only weak; it can be damaging for precisely what professors want in their students! Our default form of motivation actually may be blinding their ability to engage in deep, creative learning.

Do you want your students to be deeply transformed by their biblical and theological studies? Do you want them to be better able to transform others? Do you want them to be more equipped to think critically and creatively? If so, then you do not want to give them more motivation—if this is the type. But, as we have seen, there are more options.

4.2. Exploring Deep Extrinsic Motivation— Relevance for Identity

Phil Race and Sally Brown agree that “motivation to learn” is enhanced “by raising interest levels”—that is, intrinsic motivation—but also by “helping them [the students] to see the relevance of the topics they are working with.”26 This was a crucial addition for me as a New Testament professor and designer of theological education. Students do not always think that perceived relevance is crucial to their learning,27 but it is truly profound.

Richard Ryan and Edward Deci argue that when the student “has identified with the personal importance of a behavior,” seeing the task (or the behavior that comes from learning the task) as “relevant” to what they “value as a life goal,” they have actually shifted toward being intrinsically motivated to learn it.28 One aspect of this statement is helpful; two aspects of it need to be modified in light of the research presented above.

First, positively, it is helpful to recognize that relevance and personal importance are indeed important for deep acquisition of knowledge and skill. However, negatively, identifying with the importance of a learning task because it is relevant for a life goal, as important as that is, is actually more akin to the third level of extrinsic motivation (Abstract Importance), not the deepest level. It is still relatively abstract as it is about where they want to get in life rather than who they are and believe they must be. (Identity and goal are, of course, intimately related.) Seeing the learning as relevant to, valuable as, and integrated into their very identity is the even deeper form of extrinsic motivation (Relevance for Identity) than Ryan and Deci direct us toward.

There is one other problem with Ryan and Deci’s otherwise valuable statement above. The shift toward seeing a learning moment as relevant for what they value as a life goal is not really a shift toward being intrinsically motivated to learn it. This is a confusion of categories. Imagine a student shifting from borrowing someone else’s conviction that the learning task is important (Extrinsic Level 2, Obligation Borrowed or “introjected regulation”) to fully identifying with the value in principle because of their own value system and life goals (Extrinsic Level 3, Abstract Importance or “identified regulation”) and even finally to seeing the learning task as integral to their very sense of self (Extrinsic Level 4, Relevance for Identity or “integrated regulation”). While this progression toward depth does shift further into the heart of the person (and it is therefore being more deeply internalized), it does not thereby shift them into enjoying and finding satisfaction in the learning task itself. The basic distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is important to maintain here. I will explain why.

Remember, intrinsic motivation is about enjoyment and satisfaction in the task per se. It is not about what is internal in the learner’s psychology, but about what is intrinsic to the learner-task relationship. The deepest forms of extrinsic motivation are also highly internal to the learner—principles and values (Level 3) and identity (Level 4)—but they are nonetheless still extrinsic to the learner-task relationship. If the learner does not inherently enjoy and find satisfaction in the task itself, then his motivation is not “intrinsic” even if it is psychologically deeply internal; it must come from somewhere other than (outside of) the learner-task relationship itself—such as obligation, principles, or self-identity.

Some scholars think intrinsic motivation is essential for deep learning. It is certainly profound for deep learning. But is it essential? Is it essential for critical and creative learning? For all deep learning? No.

First, the deepest form of extrinsic motivation (relevance for identity) also enlivens critical and creative thinking. Being motivated extrinsically—if one of the deeper forms—enables the student to engage in high-quality conceptual understanding, creativity, persistence in learning, and ability to “think about and integrate information in a flexible, less rigid, and conceptual way.”29 So, no, intrinsic motivation is not essential for all deep learning.

Second, some ideas and tasks are crucial to learn deeply but are never enjoyable and satisfying in and of themselves—nor should they be. We do not actually want our students to have only intrinsic motivation. We must not cultivate the mindset or practice that they only engage in learning if they enjoy it. Many of them already have that idea, and it is a problem when trying to get them to engage in learning tasks that we know are valuable regardless of enjoyment. For such tasks, Abstract Importance (Extrinsic Level 3) and, especially, Relevance for Identity (Extrinsic Level 4) are needed, not intrinsic motivation. Our students need the variety in their program of learning.

Since we are addressing theological education in particular, consider Christ’s own suffering and his followers’ suffering for Christ and his people. Did Jesus himself enjoy the suffering he was tasked with by his Father, and should his followers?

In the days of his flesh, Jesus offered up prayers and supplications, with loud cries and tears, to him who was able to save him from death, and he was heard because of his reverence. 8 Although he was a son, he learned obedience through what he suffered. 9 And being made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation to all who obey him. (Heb 5:7–9 ESV, emphasis added)

As Jesus faced his pain and shame, he pled and supplicated the Father with strong clamour and tears for such fatal suffering to be taken away. This is not enjoyment of the task at hand!

Christ’s suffering was not (and should not be) enjoyable in and of itself. Enjoying and being satisfied with pain, injustice, and abuse is a dangerous form of psychopathology!30 And it is a misunderstanding of Christ and his calling. Jesus deeply learned something valuable—obedience—by persevering in the unenjoyable and unsatisfying task. He also gained the satisfying honor of being the source of eternal salvation to all who obey him, and the joyful task of sitting at the right hand of God’s throne. The suffering was a means to an end, not an end itself. It was “for the joy set before him” that “he endured the cross” (not enjoyed it) and “despised its shame” (not being satisfied with it). And thus he got to “sit down at the right hand of God’s throne” (Heb 12:2). While the task per se was not enjoyable or satisfying, what Jesus would deeply learn and gain by engaging it and persevering in it was relevant and valuable to himself—and to those whom he would transform through it.

In the language of this article, Christ was not intrinsically motivated to go to the cross. He rightly despised the cross and its shame in and of themselves. But he was nonetheless profoundly and deeply motivated to accomplish the task. Christ was extrinsically motivated to bear the cross and shame for us—deeply motivated, even internally motivated, but “extrinsically” motivated.

And what of Jesus’s followers? How do we learn to obey him? The author of Hebrews resumes the theme later in his sermonic epistle: we fix our eyes on Jesus (12:2–3) and “endure” difficulties so that we are “disciplined, trained, educated” (παιδεία, 12:7). Of course, “no discipline seems pleasant at the time, but painful” (12:11). This means we will not be intrinsically motivated to accomplish such learning—that would be wrong. “Later on, however, it produces a harvest of righteousness and peace for those who have received exercise [γεγυμνασμένοις] through it” (12:11). Like Christ before us and for us, we are to be deeply extrinsically motivated to endure and be educated by difficulties, for they are relevant to our very identity and calling as siblings and followers of Jesus.

Therefore we strive to deeply study and learn and practice and grow in following Christ in his mission. We bear our cross and serve others sacrificially. We should see this aspect as essential to who we are as followers of Christ, since it is part of Christ’s own identity. It is not worthwhile to pursue because we enjoy it. But suffering is deeply relevant to our core identity in Christ in this fallen world. We do not enjoy it. We should not. But that deep form of extrinsic motivation should, in fact, motivate us to persevere in learning the patience and obedience and selflessness that come through suffering in a deep and transformative way—and a way that helps us transform others.

So it is with other elements of theological education. Some tasks and aspects are enjoyable and satisfying in and of themselves—more than many of us realize and more than many of us nurture in the classroom (see §5.1 below). But some elements and tasks are simply not enjoyable. Yet they are exceedingly good. They are important for our identity as humans created by God and re-created in Christ together. And they are important for teachers to try to stimulate in a suitable way (see §5.2 below).

5. Conclusions for Practice

This article has provided a theoretical framework for understanding human motivations and their relationship to theological education. It also has attempted to stimulate you within that research-based framework to experiment practically with various forms of motivation for your students’ transformation. A few concrete classroom ideas and examples regarding intrinsic and deep extrinsic motivation will help.

5.1. Practical Experiments with Intrinsic Motivation

As we have seen, “How can I motivate my students more?” is not quite the right question. Imagine instead that you can motivate your students differently—more deeply, more appropriately, more richly. Imagine that you can help your students enjoy different aspects of biblical studies and theological thinking per se. Imagine that you can help them find satisfaction in the hard work of digging into Scripture and discussing its meaning and implications with their community of believers. Intrinsic motivation is a powerful tool for deep, transformative learning. It is a tiger among the motivations. Pursue it. There are practical ways. For example, when seeking to stir up the king of the lush jungle of joy and satisfaction—intrinsic motivation—remember four key words: Contagion, Longing, Action, Wonder.

5.1.1. Contagion

A professor’s own intrigue with and passion for his subject or skill is highly contagious. This helps stimulate enjoyment and satisfaction in the topic or skill itself. Marva Collins has famously said, “The essence of teaching is to make learning contagious, to have one idea spark another.” I have seen its impact. One student said to me after a public lecture I gave, “Thank you for inviting us into your curiosity and guiding us with you along your journey of discovery. I had never before asked those questions in that way, and I look forward to thinking more about those texts.” Contagion.

5.1.2. Longing

In addition, a sense of longing for what will be revealed and discovered is highly compelling31 and helps invigorate enjoyment in the topic or skill. I begin some classes with “The Challenge.” I put intriguing but seemingly disconnected pictures or words on the screen. One morning the slide had an elephant, an elf, a lemur, and a highway cloverleaf. The day’s topic was Second Temple Judaism and Messianic Expectation. At the beginning of class, the students must guess the connection between the images or words and the day’s topic. (They will never get it “right,” so I encourage creativity, which also brings some laughs and “situational interest.”) Throughout the learning time, then, each picture reappears in a context that finally makes sense within the topic. One morning, as the third picture was revealed (two hours after it was initially put up!), a student uncontrollably exclaimed, “Ooooh—that’s how!” Similar murmurs followed from other students. She had retained for hours the curiosity and longing for how the images could possibly be connected to the day’s topic, paying attention to the details of the topic and waiting for how it would all make sense. Longing.

5.1.3. Action

What is more, a student finds greater satisfaction in a given task when he actually experiences success in action—in the doing of it32—i.e., when he feels in concrete real time his own “self-efficacy”33 and “competence”34 in what he has been challenged to do. My previous approach to teaching critical engagement with scholarship on biblical themes involved scattered pep-talks and “motivational speeches” about how they can use constructive criticism more than they may think. Then I learned that action is profound for satisfaction in learning.

So, I divided a class into groups of five students. Each group selected a topic from a book—e.g., creation, covenant, idolatry, messiah, law, salvation, kingdom—and had to read the book’s chapter on their topic.35 As a group they had to research other secondary literature on their theme. In their group presentation, then, each member of each group had a task: one must accurately describe what Williams wrote about their theme; one must describe at least one alternative view of that theme; one must explain at least three strong points from Williams; one must explain at least three weak points of Williams’ presentation; one must summarize what their group had learned about the theme. Instead of merely being told that they could constructively critique a piece of theological scholarship better than they realized, they were given the opportunity to actually do it, to experience success in action. Numerous students reflected afterward that critical engagement was no longer that scary and foreign beast that it had seemed; it was doable—and even kind of fun. Action.

5.1.4. Wonder

A sense of wonder in subjects and skills is one of the greatest God-given tools for being intrinsically satisfied with joy in learning itself. For instance, John Steinbeck wrote about three standout teachers he had, and especially one, in a short essay to his son called “…Like Captured Fireflies”:

My three had these things in common: They all loved what they were doing. They did not tell—they catalyzed a burning desire to know. Under their influence, the horizons sprung wide and fear went away and the unknown became knowable. But most important of all, the truth, that dangerous stuff, became beautiful and very precious.

I shall speak only of my first teacher because, in addition to other things, she brought discovery. She aroused us to shouting, bookwaving discussions…. She breathed curiosity into us so that we brought in facts or truths shielded in our hands like captured fireflies.… She left a passion in us for the pure knowable world and me she inflamed with a curiosity which has never left me.… I have had many teachers who told me soon-forgotten facts but only three who created in me a new thing, a new attitude and a new hunger.36

An insatiable sense of wonder seems particularly fitting in theological education wherein the subject is the wonder-full God and the mystery of his revelation in Christ, through Scripture and creation, by the Spirit, within the community of faith. Wonder.

Based on the concepts and research presenting in this article, and perhaps prompted by these few practical ideas and experiments, think creatively and with colleagues about how you can stimulate contagion, longing, action, and wonder in your classroom, homework, and even assignments. (Yes, those too.) Experiment for the sake of your students’ enjoyment, satisfaction, and thus deep intrinsic motivation to learn, be transformed, and transform others.

5.2. Practical Experiments with Deep Extrinsic Motivation

Finally, also imagine helping your students find relevance in understanding and communicating Scripture and in responsible theological thinking, even in the parts and at the times that are simply not fun. Push beyond surface-level rewards and punishments while being conscious that such motivations are what students have been trained to crave. Allow your students to borrow your sense of obligation—i.e., tell your students that this idea or that task is important—but do not be satisfied to stop there. Do not set them up merely to introject the values of their respected authority figures (as good as that is at one level). Help them see the importance of an idea or task within their own value system, even though this is relatively abstract. Yet do not stop even with that, as good as that type of motivation is for certain tasks.

Rather, picture your students also seeing the relevance of various aspects of their theological education for the essence of who they are as humans, in Christ, and in a community.37 That form of extrinsic motivation is a lion among the motivations. It is the king of the arid savannah where joy and satisfaction may be hard to come by but where life and learning are still vital and good to hunt down. Consider how to stimulate relevance for identity. There are practical ways. Here are two ideas, one seeking to stimulate Abstract Importance (Extrinsic Level 3) and the other Relevance for Identity (Extrinsic Level 4).

5.2.1. Abstract Importance

Regarding Abstract Importance, I explained to my students in Theological Study Skills a citation game that they were about to play. (Yes, you read that correctly: a citation game.) Each team would race to put different types of bibliographic information into proper Chicago style footnote and bibliography formats. Before they attempted the task—which, although made more interesting and fun by the game, still seemed pointless to many of them—I paused to share an idea as to how this was important for something they already deemed worthwhile:

It is obviously important to give credit where credit is due—in general. But why do you really need to learn details of formatting it? Parentheses? Commas?!

Think about it this way: When you go to a different culture or begin a new job, you must learn seemingly strange customs, ways the people in the new environment do things. They have reasons for doing what they do, even if it is lost on you at first. It would be easy to simply not care about and not learn the new ways. But then you would not have as much impact on the new environment as you otherwise could. You wouldn’t make as much sense to the new listeners. You may even offend your new neighbors or colleagues. The skill of paying careful attention, learning, practicing, and adhering to new ways of doing something within a new culture is an important life-skill. And it is precisely that skill that you are practicing with citation styles. Practice for life.

The learning task itself was actually helpful for equipping them to practice something they already thought was important, and now they saw the connection. It was still relatively abstract. But there was nevertheless now a more powerful force within them to learn and do it. (And practicing citations in a game was like taking medicine with a spoonful of intrinsic motivation.)

5.2.2. Relevance for Identity

Finally, regarding Relevance for Identity, the deepest form of extrinsic motivation has to do with seeing the theological subject, or task, or skill as relevant for their very identity—as a human, in Christ, within relationships. How can we help rouse the king of beasts in our students, helping their theological education be relevant for their identity? Here is one final story, given to stimulate your own creative thoughts, conversations, and experiments.

I had a student, Wade, who did not like to exegete books or passages of Scripture. He did not see the point in analyzing the minutiae of grammar and syntax (which was his understanding of what exegesis was) or exploring socio-historical issues related to texts. He did not even see the value in constantly asking, “But is that what the author intended?” because, he reasoned, it is the Holy Spirit that gives understanding. (His theology of inspiration wrongly assumed there is no link between those two). Exegesis was certainly not inherently enjoyable and satisfying for him—he was a self-proclaimed “practical hands-on kinda guy” and did not enjoy thinking hard. And perhaps he never would enjoy such things, at least not the way some people do who are wired differently. But even more problematic than his lack of enjoyment was that Wade did not find thinking hard about authorial intent in exegesis important either. It was not relevant for pastoring. It was certainly not relevant for him to be who he thought he was or needed to be.

Over months of in-class engagement, and some out-of-class chats too, Wade became deeply motivated to exegete Scripture. A few years later he reached out to me and reflected the key change as he saw it:

I didn’t see the point. But that changed when you started comparing Bible exegesis to my relationship with my wife. And my kids too.

I’d thought for a long time that to be a true man, and to be the type of man God calls me to be, I need to listen carefully to other people—especially my wife. My dad taught me that, though I see it more clearly now that I’m married. I’ve seen it so many times. Whenever I’m not really listening to what my wife is sayin’, but thinkin’ I already know and don’t agree and what I’ll respond back, we get in big fights. And she’s always like, “That’s not what I’m sayin’!” And then I realize, I’m not being the husband God wants me to be because I’m not really listenin’ to what she really means. I’m not really being the Christian man Christ saved me to be.

And then you were like, “Asking what the author is sayin’ and really payin’ careful attention to what the Holy Spirit inspired the author to write is like listening carefully to your wife, or mom or dad, or kids, or neighbor. Relationships flourish more when you actually exegete what someone is sayin’ to you.”

And I was like, “Oh man. How can my relationship with God flourish if I don’t even really listen carefully to what he inspired and how he inspired it? If I don’t exegete his word carefully?! If I don’t even do with God what I know I need to do with my wife and kids!”

Most student motivation stories have not been this clear and exciting. Wade is a success story, but not because he started to enjoy the hard work of exegeting Scripture. (Though I do think he has grown in his satisfaction with exegesis per se, at least to some extent.) Wade is a success story because his motivation to learn responsible exegesis turned into a lion within him as he realized that the call to and skills to exegete were intimately tied to his sense of self-identity before God and in relation to others. He did not merely value the abstract principle of “listening carefully” to a speaker, admitting that such practice is truly helpful and healthy for the Bible too. Even that would have been powerful. But still more powerfully, Wade understood that his own identity—as a human under God, as a man, as a Christian, as a husband—profoundly matured in a causative positive correlation with a maturing ability to exegete what others say or write, especially if the speaker is God through a human author. This shift in the type of motivation changed his learning. He not only began exegeting with more quantitative vigor. He also began exegeting with greater qualitative worth.

This article has provided a theoretical framework for understanding human motivations and their relationship to theological education. It also has attempted to stimulate you within that research-based framework to experiment practically with various forms of motivation for your students’ transformation. Ultimately, I seek to challenge you to demonstrate and nurture intrinsic task enjoyment in theological education, but also to clarify and help your students think deeply about the relevance of their training for their identity as humans in Christ within community. Remember, it is not so much about helping your students be more motivated, but better motivated. Get creative in your theological education—for the sake of your students’ deep and lasting growth, and for their consequent transformation of others.

[1] Parker J. Palmer and Arthur Zajonc, The Heart of Higher Education: A Call to Renewal (San Francisco: Jossy-Bass, 2010).

[2] Raymond P. Perry and John C. Smart, “Introduction to the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: An Evidence-Based Perspective,” in The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: An Evidence-Based Perspective, ed. Raymond P. Perry and John C. Smart (Dordrecht: Springer, 2007), 2.

[3] Cf. Jay L. Wenger, “The Implicit Nature of Goal-Directed Motivational Pursuits,” in Psychology of Motivation, ed. Lois V. Brown (New York: Nova Science Publishers, 2007); Bland Tomkinson, Rosemary Warner, and Alasdair Renfrew, “Developing a Strategy for Student Retention,” International Journal of Electrical Engineering Education 39.3 (2002), 210–18; Wilbert J. McKeachie, “Good Teaching Makes a Difference—and We Know What It Is,” in The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: An Evidence-Based Perspective, ed. Raymond P. Perry and John C. Smart (Dordrecht: Springer, 2007), 457–74.

[4] Robert Eisenberger and Linda Shanock, “Rewards, Intrinsic Motivation, and Creativity: A Case Study of Conceptual and Methodological Isolation,” Creativity Research Journal 15.2–3 (2003): 121–30.

[5] Michael Prosser and Keith Trigwell, Understanding Learning and Teaching: The Experience in Higher Education (Philadelphia: Open University Press, 2001), 3.

[6] “Explicit memory is the conscious recollection of information…. Implicit memory comprises habitual actions and attitudes, and includes such things as complex synthetic and evaluative thinking skills, as well as empathetic and aesthetic responses. The key to effective Christian teaching and training is the deep-learning goal of developing significant long-term explicit memories that are a continuous resource for life, and, even more importantly, substantial and theologically sound implicit memories that have come so much to shape the person that life decisions are habitually formed by healthy reflective practice. It is the retrieval of these long-term explicit and implicit memories that forms the basis of life decisions and actions,” according to Perry Shaw, Transforming Theological Education: A Practical Handbook for Integrative Learning (Cumbria: Langham Partnership, 2014), 135. Cf. Peter Graf and Daniel Schacter, “Implicit and Explicit Memory for New Associations in Normal and Amnesic Subjects,” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 11 (1985): 501–18; Björn H. Schott, Richard N. Henson, Alan Richardson-Klavehn, Christine Becker, Volker Thoma, Hans-Jochen Heinze, and Emrah Düzel, “Redefining Implicit and Explicit Memory: The Functional Neuroanatomy of Priming, Remembering and Control of Retrieval,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 (2005): 1257–62.

[7] Johnmarshall Reeve, Understanding Motivation and Emotion (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2009), 137.

[8] RoseAnne O’Brien Vojtek and Robert Vojtek, Motivate! Inspire! Lead! Strategies for Building Collegial Learning Communities (Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, 2009), building on Alfie Kohn, Punished by Rewards: The Trouble with Gold Stars, Incentive Plans, A’s, Praise, and Other Bribes (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1993).

[9] Vojtek and Vojtek, Motivate! Inspire! Lead!, 16.

[10] Tomkinson, Warner, and Renfrew, “Developing a Strategy for Student Retention,” 211.

[11] Wenger, “The Implicit Nature of Goal-Directed Motivational Pursuits,” 143.

[12] Tomkinson, Warner, Renfrew, “Developing a Strategy for Student Retention,” 211; cf. Graham Gibbs, Improving the Quality of Student Learning (Bristol: Technical and Educational Services, 1992).

[13] McKeachie, “Good Teaching Makes a Difference,” 471; Edward L. Deci, “Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 18 (1971): 105–15.

[14] Richard M. Ryan and Edward L. Deci, “Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions,” Contemporary Educational Psychology 25 (2000): 54–67, 55.

[15] Reeve, Understanding Motivation and Emotion, 112–13; cf. Ryan and Deci, “Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations.”

[16] Reeve, Understanding Motivation and Emotion, 113.

[17] See Gibbs, Improving the Quality of Student Learning, 4–5.

[18] Reeve, Understanding Motivation and Emotion, 16.

[19] Ryan and Deci, “Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations,” 54–67; Reeve, Understanding Motivation and Emotion.

[20] Merriam-Webster defines “introject” as “to incorporate (attitudes or ideas) into one’s personality unconsciously.”

[21] For definitions of critical thinking, see Peter A. Facione, “Critical Thinking: What It Is and Why It Counts,” Insight Assessment (2013): 1–28; Peter A. Facione, Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction (Millbrae: California Academic Press, 1990); and the interaction with his summary in Edward de Bono, Six Thinking Hats, revised and updated (London: Penguin, 2000) and Charles Kivunja. “Using De Bono’s Six Thinking Hats Model to Teach Critical Thinking and Problem Solving Skills Essential for Success in the 21st Century Economy,” Creative Education 6 (2015): 380–91.

[22] Charles Kivunja, “Do You Want Your Students to Be Job-Ready with 21st Century Skills? Change Pedagogies: A Pedagogical Paradigm Shift from Vygotskyian Social Constructivism to Critical Thinking, Problem Solving and Siemens’ Digital Connectivism,” International Journal of Higher Education 3.3 (2014): 81–91.

[23] Barbara E. Walvoord, Teaching and Learning in College Introductory Religion Courses (Oxford: Blackwell, 2008), 13–18.

[24] See Vojtek and Vojtek, Motivate! Inspire! Lead!; McKeachie, “Good Teaching Makes a Difference”; Kohn, Punished by rewards; Deci, “Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation.” Cf. Dan Pink, “The Puzzle of Motivation,” TedGlobal, July 2009, https://www.ted.com/talks/dan_pink_the_puzzle_of_motivation; Kendra Cherry, “What is Intrinsic Motivation?,” Verywell Mind, 27 September 2019, http://psychology.about.com/od/motivation/f/intrinsic-motivation.htm.

[25] Pink, “The Puzzle of Motivation”; Reeve, Understanding Motivation and Emotion, 112–13; Beth A. Hennessey and Teresa M. Amabile, “Reality, Intrinsic Motivation, and Creativity,” American Psychologist 53 (1998): 674–75; Mary Ann Collins and Teresa M. Amabile, “Motivation and Creativity,” in Handbook of Creativity, ed. Robert Sterberg (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 297–312.

[26] Phil Race and Sally Brown, The Lecturer’s Toolkit (London: Kogan Page, 1999). This is done well in biblical studies by Moyer Hubbard, Christianity in the Greco-Roman World: A Narrative Introduction (Grand Rapids, Baker Academic, 2010), 2–3.

[27] Kenneth A. Feldman, “Identifying Exemplary Teachers and Teaching: Evidence from Student Ratings,” in The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: An Evidence-Based Perspective, ed. Raymond P. Perry and John C. Smart (Dordrecht: Springer, 2007), 93–143.

[28] Ryan and Deci, “Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations,” 62.

[29] Quoting but contra Reeve, Understanding Motivation and Emotion, 112–13. The deeper forms of extrinsic motivation can also produce creativity, flexibility of thinking, high-quality deep learning—indeed robust criticality. See James C. Kaufman, Creativity 101 (New York: Springer, 2009); Eisenberger and Shanock, “Rewards, Intrinsic Motivation, and Creativity”; Judy Cameron and W. David Pierce, Rewards and Intrinsic Motivation: Resolving the Controversy (Westport: Bergin & Garvey, 2002).

[30] Otto Kernberg, “Clinical Dimensions of Masochism,” Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 36 (1988): 1005–29.

[31] Reeve (Understanding Motivation and Emotion, 137) points to the potential of “situational interest” as a spark for task interest, in turn creating or enhancing intrinsic motivation.

[32] McKeachie, “Good Teaching Makes a Difference,” 471; James H. McMillan and Amanda B. Turner, “Understanding Student Voices about Assessment: Links to Learning and Motivation” (paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Philadelphia, April 2014).

[33] Dale H. Schunk, “Self-Efficacy and Academic Motivation,” Educational Psychologist 26 (1991): 207. Cf. J. E. Susskind, “PowerPoint’s Power in the Classroom: Enhancing Students’ Self-Efficacy and Attitudes,” Computers & Education 45 (2005): 203–15. J. E. Susskind, “Limits of PowerPoint’s Power: Enhancing Students’ Self-Efficacy and Attitudes but not Their Behavior,” Computers & Education 50 (2008): 1228–39.

[34] Ryan and Deci, “Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations,” 58. Cf. Gregory C. Wolniak, Matthew J. Mayhew, and Mark E. Engberg, “Learning’s Weak Link to Persistence,” The Journal of Higher Education 83 (2012): 795–823; McKeachie, “Good Teaching Makes a Difference,” 462.

[35] We used Drake Williams III, Making Sense of the Bible: A Study of 10 Key Themes Traced Through the Scriptures (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2006).

[36] John Steinbeck, “…Like Captured Fireflies,” California Teachers Association Journal 51.11 (November 1955): 6–9.

[37] Identity should not be hyper-individualized. Fight that American short-sightedness.

Jonathan D. Worthington

Jonathan Worthington (PhD, Durham University) is vice president of theological education at Training Leaders International. He is the author of Creation in Paul and Philo and numerous articles on creation in Paul and early Judaism, cross-cultural theological education, and motivation theory.

Other Articles in this Issue

For those who enjoy debates, there has never been a debate more routinely rehashed than the debate over God’s existence...

A Generous Reading of John Locke: Reevaluating His Philosophical Legacy in Light of His Christian Confession

by C. Ryan FieldsLocke is often presented as an eminent forerunner to the Enlightenment, a philosopher who hastened Europe’s departure from Christian orthodoxy and “turned the tide” toward a modern, secularist orientation...

“Love One Another When I Am Deceased”: John Bunyan on Christian Behavior in the Family and Society

by Jenny-Lyn de KlerkIn the last two decades, Bunyan studies has seen an increase in scholarship that examines his life and thought from various angles, such as the psychological experiences and socio-political convictions found in his allegorical and autobiographical works...

American Prophets: Federalist Clergy’s Response to the Hamilton–Burr Duel of 1804

by Obbie Tyler ToddMore than any event in early American history, the duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr in 1804 revealed Federalist clergy to be the moral guardians of American society and exposed the moral fault lines within the Federalist party itself...

Hermeneutics and Historicity in the Matthean Crucifixion Narrative: A Response to Daryn Graham

by Daniel M. GurtnerThis short piece takes up some challenges to Daryn Graham’s article, “The Earthquakes of the Crucifixion and Resurrection of Jesus Christ...