I’m a Christian woman who experiences same-sex attraction. Should I call myself a lesbian?

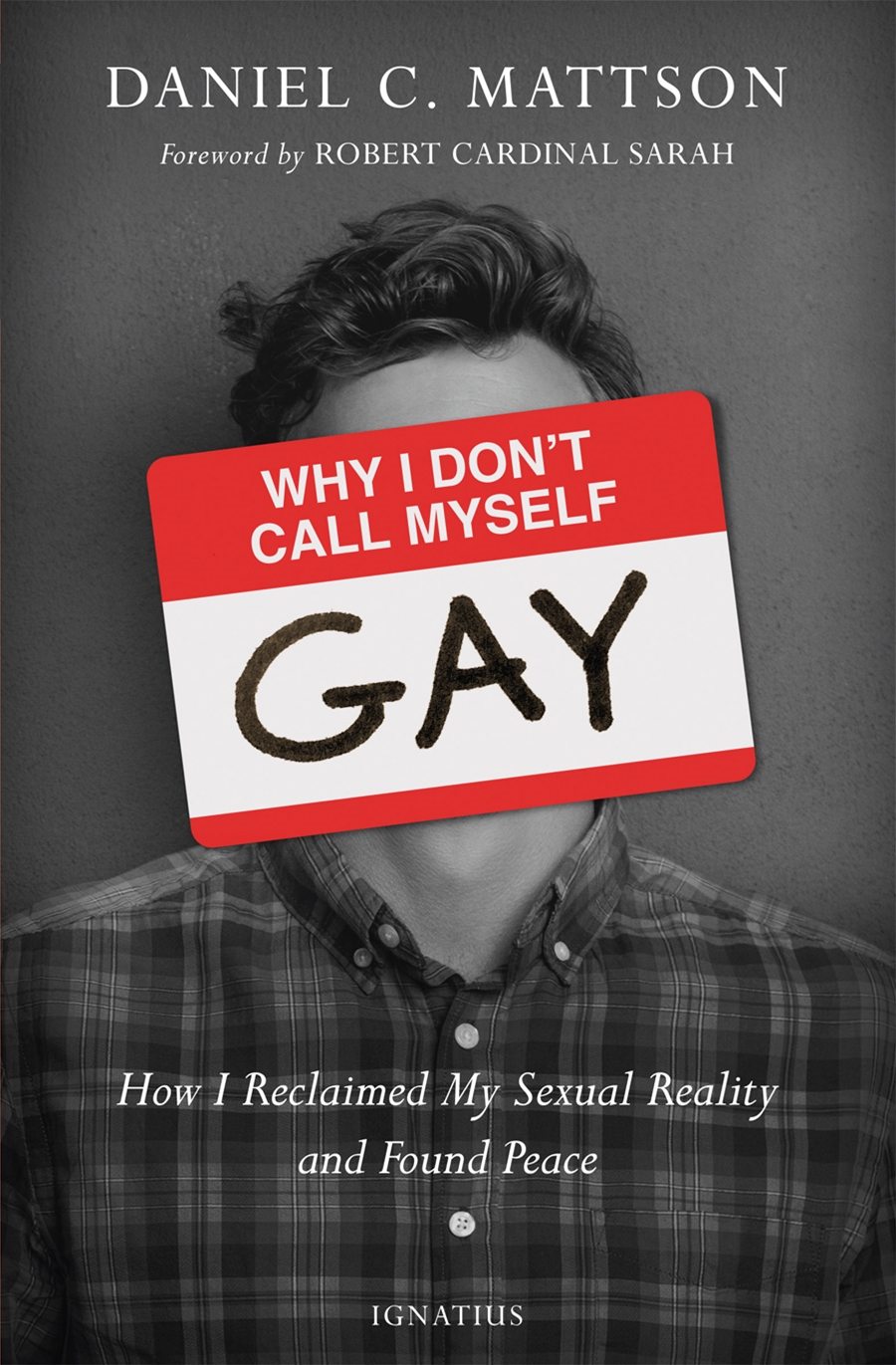

In his new book, Why I Don’t Call Myself Gay: How I Reclaimed My Sexual Reality and Found Peace, Daniel Mattson would argue “no.”

As a Roman Catholic who experiences same-sex attraction, he adds to the growing discussion within the church about labels for people like Mattson and me, and more importantly, the identities those labels imply.

Mattson’s Story

One naturally picks up this book wanting an answer to the title, but Mattson—a writer, speaker, and professional orchestral trombone player—begins instead with his story. It’s one of pain and trial, and we are given access to the most private pieces of his life. But it’s not merely a story; Mattson gives frequent commentary on how he now understands what he experiences, with a particular eye toward what, according to him, caused his same-sex attractions. “A lot of people would tell me . . . that I was born gay,” he explains. “But I see it very differently. We live in a world guided by cause and effect. Everything always comes from something” (14).

Mattson believes he “didn’t choose to be attracted to men, nor does any man” (34). It came from somewhere, and he thinks a large part of it came from his dissatisfaction with his male body, coupled with an intense longing to be like the highly masculine men he observed around him. Mattson grew up around the Catholic Church and then in Protestant circles, before eventually falling away for a time altogether. This exposure gave him enough awareness to know that his attractions were largely scorned by the church. It also gave him a desire to meet and marry just the right woman, who could allow him to live the life he dreamed of—a woman he could connect with despite his more overt attractions elsewhere.

Why I Don’t Call Myself Gay: How I Reclaimed My Sexual Reality and Found Peace

Daniel Mattson

Why I Don’t Call Myself Gay: How I Reclaimed My Sexual Reality and Found Peace

Daniel Mattson

Mattson’s honesty is commendable. But there are times when he starts to universalize, abstracting from his experience truths about whole populations, especially men who identify as gay, without further evidence or data. For example, he writes:

I really think that at the bottom of any gay male relationship, what motivates men more than anything else is a deep void that stems from lack of communion and relationship with other men. (49)

This certainly seemed to be true for Mattson and his first serious boyfriend, but he doesn’t prove that it’s always true for others.

Not Obsessed with Attraction

This extended background is important, because Mattson’s book isn’t quite like others in the field; that is, he displays a mix of commitments not typically found together. First, he rejects same-sex sexual contact and lust, which puts him firmly in line with the traditional or orthodox view. In addition, he rejects the label “gay,” because of what he believes it signals about identity and what he sees as its lack of objective foundation. However, he doesn’t see himself as morally culpable for merely experiencing same-sex sexual attraction, nor is he determined to mortify the attractions themselves. This isn’t always the case for those who reject “gay” as a meaningful or appropriate identity marker. He explains, “what I do have is the choice of what I do with that awareness [of attraction]. In this way, I’m no different than a man who sees a beautiful woman and has a choice with what to do with her beauty” (258).

This mix of commitments seems to have provided Mattson with a deep sense of peace about being a Catholic man who experiences same-sex attraction. He declares himself to not belong to his temptations, which are subjective and bound in time, but to Jesus Christ—the ultimate eternal reality.

Similarly, Mattson believes all attempts to shoehorn humans into types, through sexual orientation, are a fool’s errand. In his view, sexual orientation can only be derived from the subjective—emotions and feelings. In contrast, “the sole sexual identities that are objectively true are male and female, designed for union with each other” (91). This lines up with Christian teaching on the nature and meaning of the body as a sexed reality.

According to Mattson, the gay-rights movement has duped society by using language that makes “gay” and “lesbian” identities as opposed to proclivities. Instead Mattson wants to return to the supposed clarity of biological determinism (though, as DeFranza would note, intersex persons are not adequately accounted for), rooted in nature and Scripture, without for a moment denying that same-sex attraction is a real phenomenon. Attraction is real, but too flimsy to build an identity on. The reason he doesn’t call himself gay “is simple: [he doesn’t] think that it’s objectively true” (128).

Those who feel more concern for the pastoral care of same-sex attracted men and women might leave disheartened, as might people in the trenches of unwanted same-sex attraction.

Inspirational and Practical

Mattson has much to offer. In his exhortations to look to Jesus alone for true intimacy, and in his recommendations for how to live with these attractions daily, he is both inspirational and practical. His chapters addressing the particular challenge of same-sex friendship are a welcome addition to the conversation on this crucial question, for it’s one of the places of deepest confusion and fear for those with same-sex attraction.

Mattson meditates on his experience of trying to force a friendship to carry the weight of spousal love, and cautions against making friendship something it was never meant to be. I left this section wanting more clarity, however, and believe there is great theological opportunity and need for the church to detangle the differences (and similarities) between intimate friendship and spousal love, apart from sexual activity.

Who can explain attraction, in its (at times) strange choice of objects? Mattson offers the church the option of not worrying too much about it, and instead finding a way forward in the good gift of maleness or femaleness, and even in what he describes as the gift of the purifying suffering of loneliness.

This full-blooded vision of Christianity takes seriously the call to die, and doesn’t for a moment consider chastity a gift that costs too much, though it can feel at times like it costs all one has. Here he becomes not aloof, but relatable, as he describes how he won this vision through years of pain.

Mattson’s book is not perfect, but he’s at his best when he expounds why holiness is both hard and also worth it. These are deep things for the church to meditate on, needed today and by every generation of saints, as we walk by faith in Christ and not by sight.