For all their rational acumen, the New Atheists have poor memories when it comes to their own past, according to independent scholar Susan Jacoby. An outspoken atheist and critic of American religiosity in her own right, Jacoby is on a personal crusade to restore the most visible champion of skepticism in 19th-century America to a position of honor among his descendants. Her latest work, The Great Agnostic: Robert Ingersoll and American Freethought, is a roving tale of the golden age of American “freethought” and its leading spokesperson, Robert Green Ingersoll (1833–1899).

This isn’t Jacoby’s first foray into the history of skepticism and its implications for contemporary American culture. Among her nearly a dozen books are Freethinkers: A History of American Secularism (2004) and The Age of American Unreason (rev. ed., 2009). Most recently, in the wake of The Great Agnostic’s publication, Jacoby contributed a cover story titled “A New Birth of Reason” to the winter 2013 issue of The American Scholar. The issue’s cover features portraits of prominent “voices of reason” in modern history, with a photo of a confident and voluptuous Ingersoll given pride of place. According to Jacoby in the Great Agnostic, this is as it should be.

Evangelist of the Agnostic Gospel

A bit more about the man may be useful: The discontented son of an itinerant evangelist, Ingersoll “left the fold” as a young adult. Having trained as a lawyer and established a successful practice, he turned his ambitions to public office. A brief stint in Illinois politics and his increasingly apparent religious infidelity made it clear such an aspiration in the (then) religious climate of American culture was unfeasible. In the minds of Ingersoll, his sympathetic contemporaries, and Jacoby herself, he’d sacrificed a promising political career (some thought he could’ve been President) because he was too honest to suppress his religious views. He eventually contented himself by becoming America’s most public opponent of religion—especially of the evangelical faith of his youth.

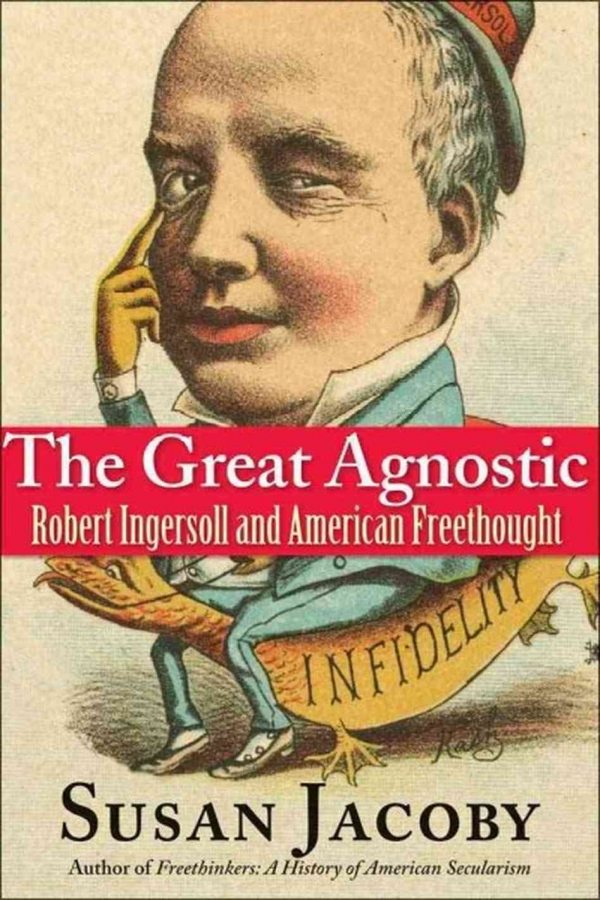

The Great Agnostic: Robert Ingersoll and American Freethought

Susan Jacoby

The Great Agnostic: Robert Ingersoll and American Freethought

Susan Jacoby

In this provocative biography, Susan Jacoby, the author of Freethinkers: A History of American Secularism, restores Ingersoll to his rightful place in an American intellectual tradition extending from Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine to the current generation of “new atheists.” Jacoby illuminates the ways in which America’s often-denigrated and forgotten secular history encompasses issues, ranging from women’s rights to evolution, as potent and divisive today as they were in Ingersoll’s time. Ingersoll emerges in this portrait as one of the indispensable public figures who keep an alternative version of history alive.

For the last quarter of the 19th century, a period in American history Mark Twain perceptively dubbed the Gilded Age, Ingersoll traveled throughout the country prosecuting religious faith, advancing his own gospel of unbelief, and voicing his opinions on political matters relevant to his secularist agenda. His heterodoxy notwithstanding, Ingersoll counted many of the nation’s movers and shakers (including a few Presidents) among his close friends. Reviled by evangelical pastors in printed sermons and the subject of regular reporting in leading newspapers, Ingersoll became a household name in the last two decades of the century. For his unblinking opposition to revealed religion and his eloquence as an orator, he earned the moniker the “Great Agnostic.” (He was also widely known as “Robert Injuresoul,” “Pope Bob,” and the “Apostle of Unbelief.”) To Jacoby’s chagrin, this legacy is all but lost on proponents of the New Atheism. Her aim, then, is to reconnect 21st-century disbelievers to their forgotten heritage. Among the whole pantheon of American freethinkers, Ingersoll is the best evangelist for the total liberty of conscience, she believes.

It’s advantageous to Jacoby that Ingersoll can be personally linked to evangelical Protestantism. Being the son of a devout and fiery minister gave him an insider’s knowledge of the goings-on in one of the most vigorous expressions of American religious life. By his own admission and the content of his speeches and writings, it’s clear Ingersoll possessed a fairly respectable knowledge of Scripture, devotional literature and hymnody, and popular biblical commentaries—though not likely more than was characteristic for a pastor’s kid at the time. He (and Jacoby after him) used his conscious departure from the faith in early adulthood as evidence he’d made an informed decision after learning all the facts of the case. Later, on the national lecture circuit and with considerable experience as a no-nonsense trial lawyer, Ingersoll constructed his arguments against religious ignorance by regaling audiences with stories of growing up in a stiflingly pious evangelical Calvinist home.

Ingersoll’s success as a public critic of faith can be partly attributed to his conversance with evangelical vernacular and his giftedness with a disarming sense of humor. He promoted his secular ideas in ways a society steeped in biblical language and revivalistic fervor would easily recognize. He gleefully affixed the “gospel” label to every tenet of his agnosticism, culminating in what he called the “great gospel of Humanity.” Concerning his commitment to remain a lecturer on freethought, he exclaimed in Pauline style, “Woe is me if I preach not my gospel!”

But Ingersoll’s unquestionable eloquence as an orator is the chief reason he gained such a wide hearing among believers and skeptics alike. In the words of one journalist at the time, Ingersoll “swayed and moved and impelled . . . the mass before him as if he possessed some key to the innermost mechanism that moves the human heart.” In a sense, he was to 19th-century agnosticism what George Whitefield was to the Great Awakening—its most dynamic and effective preacher.

Patron Saint of the New Atheists?

Though promoted as a biography, Jacoby’s book is more extended commendation of Ingersoll’s indictment against religion and his vision for a faithless future. Since his lifetime, the Great Agnostic’s reputation has suffered from accusations he was little more than an iconoclast and popularizer. He tore down the religious structures on which the American conscience depended without leaving anything in their place, and rehashed the thought of earlier skeptics (such as Thomas Paine and Voltaire) without contributing anything original to the discussion. Jacoby roundly rejects these assertions. She argues Ingersoll constructed an all-encompassing philosophy of life rooted in the universal accessibility of reason, the promise and progress of science, and the power of human compassion unshackled from religion.

In the most revealing part of her book, the afterword titled “A Letter to the ‘New’ Atheists,” Jacoby pleads with the advocates of aggressive irreligion (she mentions Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris by name here and elsewhere in the book) to “work tenaciously for the restoration of the memory of this old American freethinker.” She calls for a more holistic atheism that continues to challenge religious faith on rational grounds while also pursing its social implications, including the need to attain a more compassionate secular humanitarianism and more radical separation of church and state. Unsurprisingly, deposing the notion of America’s Christian founding is high on her action list. Jacoby is convinced Ingersoll possessed all the tools necessary for a vigorous and sympathetic atheism to succeed in America.

The problem, however, is that Ingersoll was never the public intellectual force of Jacoby’s imagination. Without question, the Great Agnostic could turn a good phrase, castigate all manner of religious hypocrisy, and play on the heartstrings of any audience. But even in his own day, Ingersoll’s friends and critics could see his limitations. The leadership of the Free Religious Association, an eclectic society opposed to supernatural faith, called his antireligious lectures “more witty than wise” and said they lacked “original contribution to liberal thought or criticism.” At the apex of Ingersoll’s fame, Samuel Putnam, the president of the American Secular Union and author of an authoritative history of freethought, acknowledged Ingersoll’s promotion of unbelief was best categorized as “essentially literature, and not politics, or philosophy, or education.” Ingersoll was useful as the man behind secularism’s bully pulpit, but not as its intellectual leader.

Jacoby admits she “paid scant attention to the philosophical debates between Ingersoll and contemporary theologians” because his true strength rested in “his impassioned portrayal” of the possibilities of human goodness divorced from a restrictive belief in God. This neglect is regrettable, since those exchanges reveal most palpably the Great Agnostic’s intellectual shortcomings. The nation’s leading secular and religious periodicals published critiques of Ingersoll from an array of Christian theologians, including George Fisher at Yale, Robert Lewis Dabney at the University of Texas, longtime British prime minister William Gladstone, and the Roman Catholic archbishop of Westminster, Cardinal Manning. In his own way, each painstakingly analyzed Ingersoll’s biblical and theological understanding. Some observed the Great Agnostic’s lack of familiarity with modern biblical scholarship and called his derision of strict biblical literalism “last-century weapons” long since “cast aside by adversaries of the Gospel who are abreast of the times” (Fisher). Others critiqued Ingersoll’s method of argumentation, characterized by “crude, hasty, and careless overstatement,” concluding that behind the brilliancy of his oratorical flair was an unstable concoction of fragmentary knowledge, haphazard assertions, and sophistry (Gladstone). In the view of the best minds of belief and unbelief alike, Ingersoll simply wasn’t up to the task of constructing an intellectually tenable case for atheism.

The opinions of the Great Agnostic’s contemporaries about his cursory grasp of scientific, philosophical, and theological matters necessarily complicate Jacoby’s glowing vision of his contribution and the possibility he could be a rallying point for 21st-century atheists. But she makes no effort to wrestle with these complex issues, and advances instead an unqualified hagiographic interpretation of Ingersoll’s place in the history of American freethought. Whatever others might consider weakness she patches over by dismissing as “Victorianism” or by defending as virtue.

The Great Agnostic isn’t the first biography of Ingersoll by an unapologetic devotee, but it is one of the least critical. Recently, a few attempts have been made to fairly assess the quality of his influence. This isn’t one of them. Nonetheless, Jacoby deserves our thanks for her effort to resurrect America’s most famous—and yet most forgotten—unbeliever. In this sense the nostalgic overtones of her narrative are excusable.