The concern for functional fathers is as old as history itself. Yet every new generation must address rampant delinquency in the home. Douglas Wilson’s book Father Hunger includes an innovative perspective on the absence or decline of fatherhood; new research to support the need for active, functional fathers in every home; and a fresh look on the effect on the culture at large. The author serves as a senior fellow at New Saint Andrews College in Moscow, Idaho, and is himself a husband, father, and grandfather (173).

The title of Wilson’s book, Father Hunger: Why God Calls Men to Love and Lead Their Families, suggests the author will provide proof for the claim that men should lead in the home. Though Wilson does indeed structure his text to demonstrate the “why,” he also addresses many other aspects of manhood ranging from genetics, calling, and desire to politics, history, and theology. Each chapter is sprinkled with fitting illustrations drawn from history, literature, pop culture, and experience in order to illuminate Wilson’s argument and connect with his readers.

Wilson argues that our understanding of fathers, and everything else in culture, cannot be put right until we rediscover God the Father (13). Wilson points out that too many churches today place undue emphasis on one of the three persons of the Trinity while practically ignoring the other two (198). Wilson observes that evangelicals emphasize having a relationship with Jesus, while charismatics place a similar emphasis on the Holy Spirit (198). To be sure, none of Wilson’s argument is designed to degrade the place of Jesus or the Holy Spirit in Christian life, but rather is intended to draw attention to a minimalized understanding of God the Father. Until a man can understand what God the Father is for, Wilson contends, father hunger will remain (199).

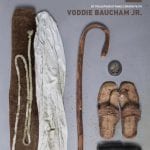

Father Hunger: Why God Calls Men to Love and Lead Their Families

Douglas Wilson

Father Hunger: Why God Calls Men to Love and Lead Their Families

Douglas Wilson

Fatherlessness is a “rot that is eating away at the modern soul,” writes Douglas Wilson, and the problem goes far beyond physical absence. “Most of our families are starving for fathers, even if Dad is around, and there’s a huge cost to our children and our society because of it.” Father Hunger takes a thoughtful, timely, richly engaging excursion into our cultural chasm of absentee fatherhood.

For the contemporary understanding of this dilemma, Wilson hinges his argument on egalitarianism and its recent effects on culture (15–17). He continues to build his case for biblical masculinity (51), godly education (82–83), Christian marriage (126–127), and biblical corporal discipline (179), explaining how each has been negatively affected by egalitarianism, or, more strongly, feminism. He boldly and powerfully presents his case, demonstrating the effects of this movement in both society and in the church. Wilson’s credibility on this subject comes in part from the fact that he doesn’t rely on claims alone but supports his assertions with empirical data.

Elevating the significance of the church in the formation, growth, and progression of fatherhood in society, Wilson later returns to his argument concerning egalitarianism, suggesting that long before the first woman was allowed to preach from the pulpit, the pulpit itself became feminized as men subverted their roles in the pulpit, the society, and the home (142). Now, with a godly, biblical understanding of manhood surrendered to feminism, education, unstable worldviews, and a weak church culture (84), the problem of father hunger runs deeper than any single man can contend with.

Wilson addresses the questions sure to arise in many readers’ minds about the role and responsibilities of the woman or mother. He gently points out that this is a book specifically about fathers and the role and responsibilities of men. To say that dad is indispensible is not to say that mom is dispensable (20). He writes, “A person should be able to write a book arguing that Vitamin D is an important component of a person’s health without being accused of making a vicious and unwarranted attack on Vitamin E” (20).

No Stone Unturned

Wilson confronts the topic of fatherhood by looking for and speaking to every possible influence that has weakened and transformed the role of a man. With the various chapters addressing the multitude of topics, Wilson’s book is just as much about evangelical feminism, politics, the fall of public and Christian education, a misappropriation of the Trinity, and a lesson on the fall of man. It seems Wilson leaves no stone unturned in his attempt to touch on every square inch of redemptive creation.

He recognizes, however, that the answer isn’t as simple as a seven-step process or a twelve-week program. In order to regain a correct understanding of fatherhood, there is much work to be done. Wilson whittles down the problems and the need for reformation to a single idea—regaining our understanding of what God the Father is for (199). And yet, herein lies a weakness. We do not live in a vacuum, nor do we somehow exist outside of society. We must learn to live out the idea of what God the Father is for precisely by seeking ways to incorporate this notion into our worldview for the sake of affecting the culture (struggling with all those problems Wilson outlines in his chapters). I fear some may seclude themselves from society in order to protect themselves from what Wilson identifies as the problem(s), but that surely doesn’t seem to be the answer.

I’m also concerned that when we consider Wilson’s subtitle, which appears to be his thesis, it seems out of place when reserved for the end of the book. Knowing, then, he’d wait until the end to develop this idea, it would have been helpful if Wilson had said so on the front end in order to better prepare his reader for what to expect. Further, I think the book would have been strengthened by developing a diagram or two to coordinate with the message Wilson was attempting to communicate. Examples would include the discussion of the four spokes of a person’s worldview (82) and the imagery of a house being built surrounded by scaffolding (96).

Nevertheless, Wilson not only achieves his goal of demonstrating the need for men to lead their families, but he does so in a refreshingly unique manner. Wilson used a masterful blend of Scripture within the text to theologically substantiate all of his claims while moving the reader from one topic to the next.