David Powlison died peacefully at his home in Glenside, Pennsylvania, at 11 a.m. (Eastern Time) on Friday, June 7, 2019, after suffering from pancreatic cancer.

He was 69 years old.

Parents

Dora Powlison, David’s mother, went by “Dodie.” She was born in Port Townsend, Washington, and moved to Hawaii in 1948, where she served for many years as a teacher at Central Union Church Preschool in Honolulu.

Peter Powlison, David’s father, was born in Turkey and raised in the Lanikai neighborhood of Kailua, on the east coast of Oahu.

In the 1920s, Peter’s father, Arthur K. Powlison—a YMCA official, sailor, and boat builder—received permission from Hawaiian officials to build an oceanfront home on a cliff, but only on one condition: he could not remove or destroy any of the rocks, which are sacred to the Hawaiian people. So he built the “Hilltop Home” (now a landmark) without chiseling or chipping a single rock, using the natural stone notches for support beams and incorporating the rocky crags of the cliff into the floor of the home.

The home overlooked Kaneohe Naval Air Station, 20 miles east of Peal Harbor. On Sunday morning, December 7, 1941, Anne Powlison was preparing to serve breakfast to her two daughters and four guests when she noticed out the window that smoke and flames were billowing from the air base from the Japanese bombing attack. She actually made eye contact with some of the pilots flying by. She wrote letters to Peter, then halfway through his sophomore year at the University of Washington, giving him daily updates on the aftermath. (Years later the letters were discovered and compiled in this book.) For three years, during World War II, the U.S. military commandeered the Powlison hilltop home to serve as a training center and vantage point to look for Japanese bombers.

After graduating from the University of Washington and serving in the Marine Corps, Peter married Dodie, and they returned to Hawaii. In 1949 he began teaching at his alma mater, Punahou’s Junior School—the same year David was born. In 1951 he helped to create the Asian History Department for the Punahou Academy.

So legendary was Peter Powlison as a teacher that when he took early retirement in 1981, the school retired his classroom—201 Griffiths—along with him.

Peter Powlison was an All-American swimmer in both high school and college. At the age of 64, after four heart bypass surgeries, he won five gold medals and set four world records at the World Masters Swimming Championships in Tokyo.

Peter collapsed and died at the age of 65 on July 10, 1987, at the University of Hawaii, after setting another world record in a Master’s Swim Meet.

David Powlison

David Arthur Powlison was born on December 14, 1949, in Honolulu, Hawaii, the first of three children to Peter and Dora Powlison. He had two younger siblings: Daniel and Diane.

Peter Powlison taught his son David to swim at the age of 3, and David went to the beaches near his home virtually every day of his childhood.

He later reflected on the culture surrounding him as a Caucasian growing up in the 50th state of the United States:

I grew up in a place that was as Asiacentric as Eurocentric—Honolulu—and most of my schoolmates were Amer-Asians. My father taught Asian history, and our dinner guests were as often as not from South or East Asia.

David’s father never pushed him. David was fascinated by the father-son relationship, and in college, he wrote a 70-page page paper on his relationship with his father for Professor Goethals of Harvard.

Like his father, David attended Punahou School in Honolulu, a private college preparatory K–12 school.

(Four years after David graduated from Punahou in 1967, a 10-year-old fifth-grade boy named Barack Obama received a scholarship to the prestigious school. He graduated high school there in 1979.)

Religion and the Quest for Meaning

The Powlisons attended a liberal mainline church—which was probably Unitarian in functional belief. As an adolescent, David reasoned:

Jesus is a really good person who cared for people less fortunate than him.

Therefore, we should be good people who care for people less fortunate than us.

That was about the sum of his thinking about Jesus and Christianity.

It was during David’s high school years that he became preoccupied with existential questions: What lasts? What matters? What is meaningful? Who am I? He became entirely estranged from his nominal mainline church. Christianity, he thought, was a polite veneer for people who refused to face hard realities.

During that time, he himself was confronted with death and depravity, including bullying (of himself and others), the murder of a classmate, suicidal friends, exposure to pornography, and seeing others self-immolating on drugs.

He later wrote:

I was a passenger in a car that killed a man as he walked down a dark country road. I can still see his face—he turned toward our headlights in the last seconds, and I looked into his eyes as we hit him.

And I sat at my grandfather’s bedside after he had a serious stroke. He was rummaging through his achievements, relationships, aspirations, and travels. He was searching for something that retained meaning, something he could hold on to, something that he could tell me mattered in life. But everything he mentioned seemed to crumble before his eyes as he spoke. In the end, all he could say was that life is more than money, and all he could do was break down and weep.

After saying goodbye, I sat on the steps outside the hospital and wept too.

Harvard in the 1960s

In 1967, David began a degree in social relations at Harvard College, earning an AB in spring 1971. He had been a high school All-American swimmer his last two years, and at Harvard he became a letter-winner on the swim team for his last three years.

But things were not well in his spiritual world.

Neither academics, nor athletics, nor career could bear the weight of identity and meaning.

Close relationships failed.

A foray into drug use almost unhinged me.

Awareness of my own egocentrism was slowly dawning.

We’re always the last to know the person in the mirror.

He had matriculated into Harvard as a math and science major, but soon migrated to psychology and social sciences, and then moved on to literature and the arts.

It was through his reading of Dostoevsky and T. S. Eliot that it slowly dawned on him that that Christianity directly addressed the big questions of life, even though he didn’t embrace the teachings of Christianity itself.

His interests during the turbulent 1960s included radical politics, Vietnam War protests, drug culture, existentialism, Hinduism, and New Age religion. He was involved with radical student politics, including the Students for a Democratic Society chapter at Harvard. In one of their conflicts with the (very Irish) Boston police, David was the designated “medic” dressed in camo but with a medic arm band. When the police line broke and began chasing the students, two policemen cornered him in an alley, and he escaped by jumping a high fence.

From 1972 to 1973 he worked as an occupational therapist at Bournewood Psychiatric Hospital, and then from 1973 to 1976 he worked as a mental health worker at McLean Psychiatric Hospital, Belmont, Massachusetts, just five miles from Harvard.

It was in the midst of this time in his life that he was radically and unexpectantly converted to follow Christ.

Conversion to Christ

At Harvard, David’s best friend and roommate, Bob Kramer, had become a Christian when they were 20 years old. They both thought about the same kinds of questions, and began an ongoing conversation and debate for the next five years.

David remembers:

I was stubborn.

I could follow the plausible logic of Christian faith. But every train of thought came to the same dead end.

I did not want someone to rescue me.

I did not want someone to tell me what to do.

I wanted to do life on my own and on my own terms. But God had other ideas about how to do my life. He was merciful.

One Sunday evening, on August 31, 1975—some four years after they had graduated from Harvard—Bob spoke to David with unexpected, uncharacteristic candor. They had spoken many times about the usual issues of Scripture and Christ and philosophy, going round and round the mulberry bush, with David always dodging.

But that night Bob got very personal with him.

David, Diane and I really love you.

I respect you as much as anyone I know . . .

But what you believe . . . and how you are living . . .

You are destroying yourself.

David recounts what happened next:

I knew he was right. The Holy Spirit used his words as an armor-piercing shell. I came under comprehensive and specific conviction of my sinfulness, uncleanness, unbelief, and unacceptability before Christ. It was a my-whole-life-passing-before-my-eyes moment. I felt the weight of many sins. The two that cut me the deepest were not on the popular list of heinous transgressions.

As a man with an existentialist streak, I had believed that despair, not joy, got last say.

And as someone who wanted to run my own life, I had not believed the love of God in Jesus Christ, but relentlessly rejected him.

I realized my wrong on both counts.

When I responded (one minute later? Ten minutes?), I asked, “How do I become a Christian?”

Bob shared with him Ezekiel 36:25–27, a promise from the God of hope:

I will sprinkle clean water on you, and you shall be clean from all your uncleannesses, and from all your idols I will cleanse you. And I will give you a new heart, and a new spirit I will put within you. And I will remove the heart of stone from your flesh and give you a heart of flesh. And I will put my Spirit within you, and cause you to walk in my statutes and be careful to obey my rules. (Ezek. 36:25–27)

David continues:

Bob invited me to ask God for mercy. I beseeched God for mercy. God was merciful. Promises from eons ago proved true—God willingly saves, forgives sins, creates a new life, gives his own Spirit, promises great help to obey. He did all this. He found me and led me home. I was surprised by joy and by the love of Jesus.

David didn’t “ask Jesus into his heart.” Rather, he cried out to be rescued: “God, be merciful to me, a sinner!”

Bob gave David a simple “New Life” booklet, written by the evangelist Jack Miller, that pulled the pieces together for David about what it meant to respond to Christ in faith.

By now it was late, and he drove home by himself. He didn’t have any sense of the category, “Oh, I’ve become a Christian.” Rather, he sat there in the car, thinking to himself: Huh, that’s interesting. I never thought of myself as a sinner before.

When he got into his apartment, having been hammer-blasted with a reality, he went to sleep.

He woke up the next morning and was absolutely flooded with joy. The first thoughts that ran through his mind after his awakening were, I’m home. I’m a Christian.

He later wrote:

It was as though my entire life had been walking hot, dusty roads looking for something which wasn’t God, but he was looking for me, and then finding myself at home, and finding that I had been found and loved. I’m a Christian.

At the age of 25, he had been reborn.

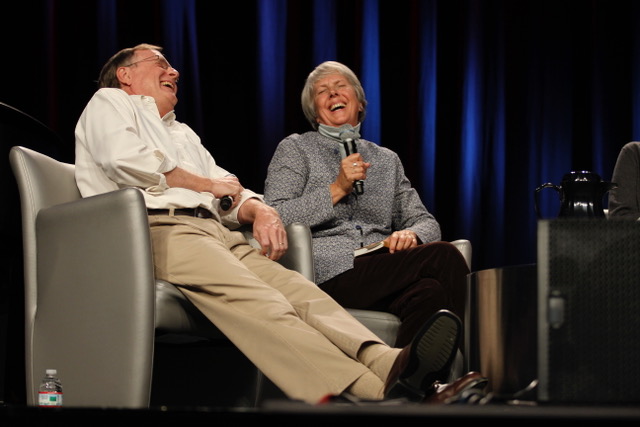

[And here is David’s final interview, shortly before he died—an hour-long conversation with Bob Kramer on friendship.]

But as an adult convert, he still felt like something of an outsider, something he never totally lost:

Subsequent educational and practical experience—a degree in social relations at Harvard College, ’60s-style alienation from capitalist and nationalist values, three years of work on the wards of McLean Psychiatric Hospital, and doctoral studies at the University of Pennsylvania—have reinforced habits of critical disenculturation and dislike of Whiggish triumphalism. As an adult convert to Christianity, and as a participant in a sometimes triumphalist and parochial movement, I can still find myself a stranger in the sometimes strange land of conservative Protestant Christianity.

Seminary and Marriage

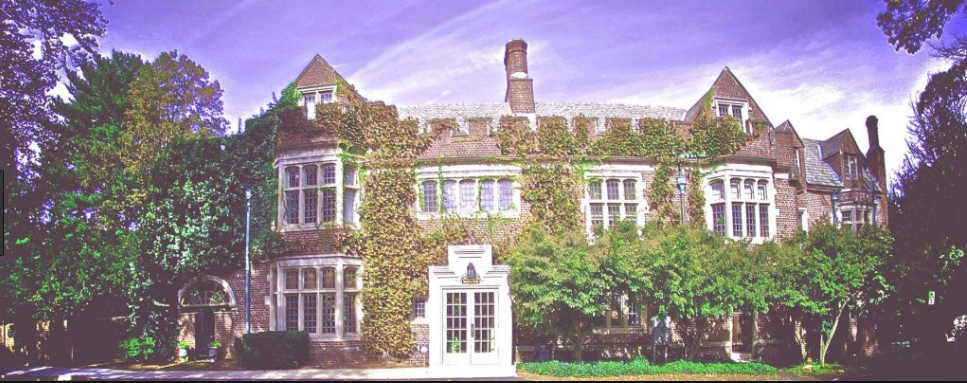

In fall 1975, David met Nancy Gardner. She was giving a multi-media presentation at an art festival held at Westminster Theological Seminary in Glenside, Pennsylvania. Bob Kramer was now a student at WTS, and David—a brand-new believer—was visiting as a prospective student.

A year later, in fall 1976, David was enrolled at WTS. The Kramers invited Nan and David to lunch at their place. Nan had come to Philadelphia to photograph a WTS student who was an artist and did his pottery in the basement of the counseling center, where he lived. She turned it into a multimedia presentation: “The Potter.”

David and Nan encountered each other a few more times in Philadelphia and did things together with others, but without really dating. That winter, they served together as counselors at a middle school kids FOCUS camp at Owl’s Nest, New Hampshire. FOCUS was a ministry to private prep schools in New England / Mid-Atlantic states (similar to the Bash Camps in the UK where John Stott came to Christ). Bob Kramer and Charlie Drew were friends of theirs and involved with FOCUS. It was freezing outside, but David and Nan went cross-country skiing together and skated on the black ice out to an island in the lake with the kids, having a blast.

Years later, Nan remember that night in a poem to David:

Remember that full moon magic night

Gliding seamless

On a New Hampshire lake

With all the kids in one long whiplash

And we two

Too shy to hold hands

Holding onto each other’s shadows

And oh the stars

In the mirror night!

Stars falling all around us

Falling at our feet

We cut through their light

And I was falling for you

Your full moon heart

And your blue coat!

Remember the island

Tree shadows calligraphic in the snow

Writing what seemed like Scripture

And we—surrounded by kids

Were only two

Then

Skating back

The cold snap rush

Upon our faces

And Light

Pouring into light

Somehow we knew

He enrolled as a master of divinity student at Westminster Theological Seminary in Glenside, Pennsylvania, graduating from seminary in 1980. David and Nan had three children: Peter (1980), Gwenyth (1982), and Hannah (1986).

Biblical Counseling

That same year he became a writer, editor, and counselor at CCEF (Christian Counseling and Education Foundation), founded in 1968 in Glenside, Pennsylvania. David also became a visiting professor at Westminster Theological Seminary.

From there, he received an MA (1986) and then a PhD (1996) from the University of Pennsylvania, writing his dissertation in the subject area of history of science and medicine: “Competent to Counsel? The History of a Conservative Protestant Anti-Psychiatry Movement” (later published at The Biblical Counseling Movement: History and Context.)

In 1970, Jay Adams, a 41-year-old Presbyterian minister, published a book entitled Competent to Counsel, which effectively launched an anti-psychiatry movement among American, conservative Protestants. Partly inspired by O. H. Mowrer and Thomas Szasz, Adams made three primary claims: (1) modern psychological theories were bad theology, misinterpreting functional problems in living; (2) psychotherapeutic professions were a false pastorate, interlopers on tasks that properly belonged to pastors; (3) the Bible, as interpreted by Reformed Protestants, taught pastors the matters necessary to counsel competently.

Adams called this “nouthetic” (from the Greek word, noutheteo, “to admonish”) counseling. Institutional forms soon developed, which were in conflict with three powerful professional constituencies: (1) secular psychological professions dominated 20h-century discourse and practice regarding problems in living; (2) the mainline Protestant pastoral counseling movement had shaped religious counseling from the 1940s; (3) a rapidly professionalizing community of evangelical psychotherapists shared Adams’s conservative Protestant faith but looked to integrate that faith with modern psychologies.

Before David Powlison’s work, no one had studied this conflict over professional jurisdiction that was being fought between Adams and the evangelical psychotherapists. He worked almost exclusively from primary sources, including interviews, publications, and case records.

At the end of the day, Powlison wrote:

Adams gained followers among pastors and their parishioners, but largely lost the inter-professional conflict.

In the 1980s evangelical psychotherapists successfully asserted their claim to cultural authority over problems in living, extending their institutional power in higher education, publishing, and the provision of care.

The nouthetic counseling movement became isolated from the mainstream of conservative Protestantism; its institutions languished; fault lines emerged internally. But in the 1990s, nouthetic counseling again began to prosper.

CCEF—David’s employer—explains their own relationship to this movement and how they developed over the years:

CCEF’s early history was largely prophetic and therefore polemic. The church was challenged to rethink its beliefs about why people struggle and how to help them when they do. CCEF called pastors and seminaries back to the primacy of Scripture as the basis for thoughtful and effective pastoral care and counseling. From the beginning, there was always a concern to define what could legitimately be learned from modern psychology, but Scripture provided the orienting “generalizations”: a God-centered view of people and problems and solutions. What was at stake was which source would be primary.

As CCEF entered the 1980s and ’90s, it was apparent that the second and third generation of leaders benefited from the strengths of their predecessors as well as learned from their weaknesses. They moved CCEF in a direction of increased sensitivity to human suffering, to the dynamics of motivation, to the centrality of the gospel in the daily life of the believer, the importance of the body of Christ, and to a more articulate engagement with secular culture.

Legacy of David Powlison

David Powlison’s legacy will begin within his own family. He was a man who dearly loved his wife, his children, and his grandchildren.

His legacy extends to those whom he instructed and touched through the biblical counseling movement, in particular through CCEF and Westminster Theological Seminary.

David was not a prolific book author, by some standards. He was, however, a prolific essayist, and his booklets in particular are filled with gentle wisdom and deep reflection on how the Word of God speaks into every part of life. His final full-length books were devoted to some of the themes he taught particularly well:

- Making All Things New: Restoring Joy to the Sexually Broken

- God’s Grace in Your Suffering

- Good and Angry: Redeeming Anger, Irritation, Complaining, and Bitterness

- How Does Sanctification Work?

The book he was working on when he died is scheduled to be released this fall:

On May 23, 2019, David Powlison was scheduled to give the closing comments at the Westminster Theological Seminary Graduation Ceremony. He was unable to attend, however, because he was receiving hospice care at home. His remarks were read in his absence, and he pled with the students—about to begin their public ministries—as follows:

My deepest hope for you is that in both your personal life and your ministry to others, you would be unafraid to be publicly weak as the doorway to the strength of God Himself.

Why Not Me?

In his suffering book, David Powlison noted that so often our initial reaction to painful suffering is:

Why me?

Why this?

Why now?

Why? . . .

He wrote:

[God] comes for you, in the flesh, in Christ, into suffering, on your behalf. He does not offer advice and perspective from afar; he steps into your significant suffering. He will see you through, and work with you the whole way. He will carry you even in extremis. This reality changes the questions that rise up from your heart. That inward-turning “why me?” quiets down, lifts its eyes, and begins to look around. You turn outward and new, wonderful questions form.

Why you?

Why you?

Why would you enter this world of evils?

Why would you go through loss, weakness, hardship, sorrow, and death?

Why would you do this for me, of all people?

But you did.

You did this for the joy set before you.

You did this for love.

You did this showing the glory of God in the face of Christ.

As that deeper question sinks home, you become joyously sane. The universe is no longer supremely about you. Yet you are not irrelevant. God’s story makes you just the right size. Everything counts, but the scale changes to something that makes much more sense. You face hard things. But you have already received something better which can never be taken away. And that better something will continue to work out the whole journey long.

The question generates a heartfelt response:

Bless the Lord, O my soul, and do not forget any of his benefits, who pardons all your iniquities and heals all your diseases, who redeems your life from the pit, who crowns you with lovingkindness and compassion, who satisfies your years with good things so that your youth is renewed like the eagle.

Thank you, my Father. You are able to give true voice to a thank you amid all that is truly wrong, both the sins and the sufferings that now have come under lovingkindness.

Finally, you are prepared to pose—and to mean—almost unimaginable questions:

Why not me?

Why not this?

Why not now?

If in some way, my faith might serve as a three-watt night-light in a very dark world, why not me?

If my suffering shows forth the Savior of the world, why not me?

If I have the privilege of filling up the sufferings of Christ?

If he sanctifies to me my deepest distress?

If I fear no evil?

If he bears me in his arms?

If my weakness demonstrates the power of God to save us from all that is wrong?

If my honest struggle shows other strugglers how to land on their feet?

If my life becomes a source of hope for others?

Why not me?

Of course, you don’t want to suffer, but you’ve become willing: “If it is possible, let this cup pass from me; yet not as I will, but as you will.”

Like him, your loud cries and tears will in fact be heard by the one who saves from death.

Like him, you will learn obedience through what you suffer.

Like him, you will sympathize with the weaknesses of others.

Like him, you will deal gently with the ignorant and wayward.

Like him, you will display faith to a faithless world, hope to a hopeless world, love to a loveless world, life to a dying world.

If all that God promises only comes true, then why not me?

See also:

- Jeremy Pierre, Biblical Counseling and the Legacy of David Powlison

- Ray Ortlund, Thank You, David Powlison

- Kevin DeYoung, Remembering David Powlison

- John Piper, He Sees with New Eyes: My Love for David Powlison (1949–2019)

- Paul Miller, What It Was Like to Be David Powlison’s Friend

- Paul Tripp, Tribute to David Powlison

- Tim Keller, Reflections on David Powlison