When Evgeny Bakhmutsky’s grandfather baptized him, the older man cried—but not just happy tears.

“He was crying because he knew I might be arrested the next day,” Bakhmutsky said. “And he was crying because he knew Christianity is a road to suffering and pain and likely death.”

Peter Bakhmutsky wasn’t being overly dramatic. In 1945, the pastor had been exiled to the labor camps in Siberia, shoved from one mine to another. Peter’s son—Yevgeny’s father—had married a girl whose father was also an exiled pastor and whose grandfather had been killed for his faith.

“In our family, at age 5, you started to memorize Scripture completely, with all your heart,” Bakhmutsky said. “Because you’ll probably be in prison one day, and it’s better to have the Bible with you.”

The 20th century was hard on Christians in Russia. Under Vladimir Lenin, and then Joseph Stalin, and then Nikita Khrushchev, and then Leonid Brezhnev, Christians were beaten, imprisoned, and killed in an attempt to eliminate all organized religion. And it almost worked. Under the Soviets, the number of Russian evangelicals dropped to 25 percent of its pre-1917 size, according to the Center for the Study of Global Christianity (CSGC).

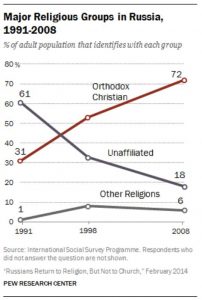

And then, in an early-’90s tumble of countries declaring independence and the Berlin Wall hitting the pavement, the Soviet Union was gone. As the Russian Federation sorted itself out, religious repression eased. From 1991 to 2008, the number of religiously unaffiliated plummeted from 61 percent to 18 percent, while those willing to say they were Russian Orthodox shot up from 31 percent to 72 percent (and has stayed there.)

And then, in an early-’90s tumble of countries declaring independence and the Berlin Wall hitting the pavement, the Soviet Union was gone. As the Russian Federation sorted itself out, religious repression eased. From 1991 to 2008, the number of religiously unaffiliated plummeted from 61 percent to 18 percent, while those willing to say they were Russian Orthodox shot up from 31 percent to 72 percent (and has stayed there.)

The “other religion” part—which included Islam, Catholicism, and Protestantism—rose from 1 percent to 6 percent and kept climbing. By 2016, almost 10 percent of the country was Muslim, nearly 1 percent was Catholic, and about 4 percent was “other,” which included Protestants.

As percentages go, that’s really small. Even smaller is the number of evangelicals—today about 1.2 million, or less than 1 percent, according to CSGC.

But it isn’t zero. With the pressure off, Russian ministries began to grow. And with the doors open to missionaries, thousands poured in to help. One was John MacArthur, who helped to open both a pastors’ training center and also a seminary. Over the past 30 years, a small but steady stream of biblically trained pastors began leading churches, publishers began to translate Reformed authors, and a TGC-type website started posting gospel-centered content daily.

The church Bakhmutsky planted nine years ago has doubled in size over and over, growing from 17 attendees to 500. (Last year, they planted a church of their own.) In 2015, the church started a network of pastors dedicated to revitalizing churches and planting new ones; since then, it has grown from 32 pastors to 100. Last October, its initial conference drew 500 to hear Capitol Hill Baptist Church pastor and 9Marks president Mark Dever.

“When people think about evangelical Christianity in Russia, they think, Wow, it’s so small and seems to have no future,” said Bakhmutsky—and he’s right. Recent crackdowns on evangelistic activities have been severe enough to get Russia listed as one of 16 countries of particular concern by the United States Commission for International Religious Freedom in 2017. This year, Russia showed up for the first time since 2011 on Open Doors’ 50 worst countries for Christians.

“But I’m saying we’re just beginning,” Bakhmutsky said. “I see how the church of Christ is flourishing.”

Baptists in the Motherland

Baptists—the largest non-Pentecostal evangelical denomination in Russia—came into Russia through Germany. Catherine the Great, herself a German, opened Russia to “all foreigners” in 1763. Thousands of Germans, tired from a 250-year-long string of wars, moved in.

They were supposed to keep their religion to themselves, but that’s hard for a Baptist to do. (“Every Baptist is a missionary,” taught preacher Johann Gerhardt Oncken, who sent European Baptists to Russia in the mid-1800s to spread the faith.) By 1867, German Baptists were baptizing the first Russian convert in a river after dark. Two years later, the first Russian Baptist church was founded.

The Baptists, along with other non-Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) denominations—grew fast enough to worry the establishment church. The ROC had begun even before Russia itself, when Prince Vladimir made Eastern Orthodoxy the region’s official religion in 988. Though it moved out from under Constantinople’s authority in 1448, the ROC kept the Byzantine tradition of a close relationship with the state.

That’s how, in the late-1800s, its leaders were able to forbid Baptists from assembling, try them in Orthodox courts, and make it hard for them to find housing.

The tables turned briefly after the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917. Vladimir Lenin’s atheist government halted all subsidies for ROC church maintenance, stopped recognizing church marriages, and took control of all church-run schools. The “Decree on Separation of Church and State” declared that “every citizen has the right to adopt any religion or not to adopt any at all.”

It sounded good on paper, but the atheist state killed 28 ROC bishops and many more priests in the first two years, stripping the rest of their civil rights. The Baptists were ignored only because the Soviets thought their growth would weaken the ROC.

Being left alone suited the Baptists, whose numbers were boosted by Russian evangelist Wilhelm Fetler (who graduated with honors from Spurgeon’s College). They were also helped by Russian prisoners of war returning from Germany, where 2,000 had been converted through the aid work of German Baptists. As the number of Baptists grew, the faithful got to work caring for the poor and orphans made destitute by World War I, the Russian Revolution, and a severe famine in the early 1920s.

“The Soviet plan: to foster Baptist activities and thus enfeeble orthodoxy,” Time magazine reported in 1929. “Last week the shrewd Soviets had to admit they had blundered.”

Indeed, the Baptists had gained so much influence through their social work that in April 1929, the Soviets limited church activities to religious services conducted in religious buildings. No one younger than 18 could participate. All churches had to register. And non-state communes were dissolved.

For the next decade, Stalin’s persecution of all Christians—and anyone else who opposed him—grew bad enough to be dubbed the “Great Purge.”

Soviet Persecution

Between 1921 and 1980, the Soviets killed 20 million Christians, according to CSGC estimates. “The persecution was gory,” Bakhmutsky said.

In 1986, the “known number of religious prisoners” in the Soviet Union was 397; of those, 315 were Christians; of those, 170 were Baptists. One was pastor Nikolai Baturin, who hadn’t finished his prison term when he was given another because of his continued Christian witness. A second was Vladimir Khailo, whose children were forcibly removed before he was arrested himself. Another was Anna Chertkova, who was injected with drugs to treat her “severe mental disorder” of Christianity. (It didn’t work. One of her letters begins, “I greet you all in the love of our Lord Jesus Christ. . . . Eternal glory to God for everything!”)

The pressure stayed high until 1991, when the Soviet Union disintegrated into 15 independent countries.

“As late as July 1989 I had Bibles and other Christian literature confiscated by Soviet customs officials,” wrote Mark Elliott, then director of the Institute for East-West Christian Studies at Wheaton College. “[J]ust one year later, in August 1990, as part of an exchange program with Moscow State University, my students cleared customs with quantities of Christian literature, no questions asked.”

As soon as they could, thousands of Christians fled the country. “Out-migration was huge and really hurt all evangelical denominations,” Elliott told TGC.

But not everyone left. And the door that was open to migration worked both ways, letting in thousands of missionaries.

“After the breakdown of the Soviet Union, religion replaced the philosophy of scientific atheism and Marxism-Leninism,” Vitaly Proshak wrote for the International Mission Board. “[I]t marked the beginning of a spiritual revival in Russia.”

Schools and Books

The Christians who remained quickly split themselves from the one official Protestant denomination into at least 35 more, and then got to work. Elliott called it “an explosion of independent grassroots mission enterprises”—within 10 years, Russians started ministries in hospitals, orphanages, prisons, and soup kitchens; founded Christian publishing houses; and formed professional networks for Christian lawyers, doctors, artists, and entrepreneurs.

At the same time, missionaries poured across the border. The “admittedly conservative estimate” of 1,100 foreign missionaries in the former Soviet Union in 1993 jumped to an estimated 4,400 in 1995 and 5,000 in 1997. At the same time, the 150 missionary organizations working in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe in 1982 swelled to 311 in 1989, to 691 in 1993, then to almost 1,000 in 1997.

One of those organizations was the Slavic Gospel Association. President Robert Provost helped to found seminaries, start pastoral training centers, and send Russian pastors to John MacArthur’s Shepherds Conference—because a church that has been locked up, beaten, starved, and worked to death is not exactly well-educated.

Seeing the need and the opportunity, MacArthur “did a number of pastoral conferences,” Bakhmutsky said. The Slavic Gospel Association and MacArthur’s The Master’s Academy International helped launch several Bible schools and seminaries—including Novosibirsk Theological Biblical Seminary (2000) and the Samara Center for Biblical Training in Russia (2000)—which began steadily turning out pastors trained in biblically sound doctrine.

By 2019, the Novosibirsk seminary had turned out more than 200 graduates, and the Samara training center had 475 graduates in expository preaching and around 100 in more intense graduate-level classes. (This year, the center anticipated about 30 people signing up for its part-time preaching program; they had 65.)

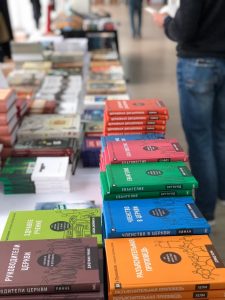

Meanwhile, a missionary to Ukraine noticed “there weren’t a lot of good books available.” (Bakhmutsky can remember when the Bible and The Pilgrim’s Progress were the only theological books in Russian.) Danny Foote and a missionary friend grabbed John Piper’s Seeing and Savoring Jesus Christ and a translator, then a typesetter, then a proofreader. Then they did it again with another book. (Along the way, TGC hopped in with some financing and support.)

“When we started, there wasn’t that much interest in stuff that was Reformed—Piper and Keller and such,” said Foote, who published in Russian to reach more readers. “But now there’s a big enough market that we compete with different publishers trying to get titles.” (He’s published Keller’s Center Church and Piper’s Don’t Waste Your Life, but the bestseller that’s “hard to keep in print” is The Jesus Storybook Bible.)

The Samara training center was translating too, assisting publishers with commentaries. One of its graduates began managing translations of the Puritans. And at its annual pastors’ conferences—which have featured speakers like MacArthur, Piper, and Paul Washer—it started giving away titles like J. C. Ryle’s Old Paths or Holiness.

“I am so thankful to the Lord,” Russian theology instructor Igor Gerdov said. He feels book-rich when compared to some of his friends in Western Europe. “There are very few [Reformed] books in Italian, for example. But when I teach theology, I have Wayne Grudem’s systematic theology, and Berkhof’s systematic theology, and Millard Erickson’s systematic theology. I also have James Montgomery Boice, and Charles Ryrie, and Calvin’s Institutes—all of these are in Russian.”

This spring, Keller’s Walking With God Through Pain and Suffering and Bakhmutsky’s Here Is Your Happiness were released from the same major publisher on the same day.

“It’s the first time in Russian history that we have the largest Russian publishing house publishing Protestant authors,” Bakhmutsky said. “It’s amazing. The books are going to be in all major Russian bookstores across the country. So we’re praying for great fruit off of that.”

It’s good news in a country that’s begun cracking down on religious freedom again.

Back to Restrictions

Starting with a 1997 law that required all religious groups to re-register with the government, the Kremlin has been regularly pushing against non-Orthodoxy. In 2016, it outlawed non-Orthodox Russians from evangelizing outside their church buildings. In 2017, Jehovah’s Witnesses were labeled an extremist group and banned. In 2019, a 71-year-old Baptist pastor was charged with illegal missionary activity, and two Baptists were fined for offering religious literature at a bus stop.

Foreign missionaries have especially been viewed with suspicion. By 2014, all non-Russian missionaries staffing the Samara training center had their visas denied. (“Thankfully, it was not the end of the world,” Gerdov said. Enough Russian theologians had been trained to take their place.)

USCIRF reported that “Russian legislation targets ‘extremism’ without adequately defining the term, enabling the state to prosecute a vast range of nonviolent, nonpolitical religious activity.” While the actions, particularly against Jehovah’s Witnesses, worry religious freedom experts, many Russian Christians on the ground are shrugging.

“When you hear that people in Nigeria are dying for their faith, it’s hard to say this administrative fine is persecution,” Gerdov said. “If you call it persecution, then the word lacks its significance. . . . Overall, in the history of Russia, we have an unprecedented amount of good resources available.”

So Christians are taking full advantage.

Russian Bible Church

Bakhmutsky is from Siberia, but he didn’t plant his church there.

“The Siberian church is so strong because the Communists sent a great many pastors there,” he said. “And now the Siberian church is sending me as a missionary back to Moscow and other places.”

Moscow is the most influential city in Russia—think New York City and Washington, D.C., rolled up together, with more people than both combined. Bakhmutsky planted the Russian Bible Church (RBC) there in 2009.

The church is part of the Union of Evangelical Christian-Baptists of Russia denomination, which Bakhmutsky says is “generally conservative evangelicals. You can find some Reformed churches, but Russia didn’t directly experience the Reformation, so it’s not really our term.” (And like Baptists in the United States, the Arminian wing and Calvinist wing have serious disagreements.)

Bakhmutsky’s RBC has gathered more than 500 weekly attendees over the past 10 years, many of them new converts to Christianity.

“In our three-hour Sunday service we have a moment where people can come forward—we now limit it to 10 people only—and they can share who they’re going to preach the gospel to this week,” he said. “The whole congregation prays. And can you imagine, after a few months or years, you have a person come who says, ‘You’ve been praying for me.’ It’s the best personal evangelism seminar, happening every Sunday.”

RBC’s new members class—even with some repeat attendees and some sitting in from other churches—draws about 150 a year. It’s one of the ways Bakhmutsky is working on ecclesiology—one of the most significant problems he sees in the Russian church.

In the past, “we got many missions, and they were thinking more about projects than ecclesiology,” Bakhmutsky said. Russian churches “started to redefine ecclesiology through missiology. [The result was] less gospel, more pragmatism.”

Russian churches started to redefine ecclesiology through missiology. [The result was] less gospel, more pragmatism.

In some churches, the pastor decides what to preach—and sometimes, who will do the preaching—on Sunday when he gets to church, said Arman Aubakirov, who spent more than a year visiting Russian churches and ministries for 9Marks. “And those sermons are just talks. None of them is even close to expositional.” Not only that, but many churches no longer require membership.

In 2017, Bakhmutsky and Aubakirov met through their involvement with 9Marks. It didn’t take long for them—and the 9Marks staff—to see a hole that could be filled.

9Marks in the Former USSR

For 18 months, Aubakirov showed up at Christian conferences all over Russia and Ukraine. He connected with the MacArthur circle in Samara. He met with as many smaller publishers and churches and ministries as he could find. And he joined Bakhmutsky’s Russian Bible Church, which was by then hosting interns, weekend workshops, and a pastors’ conference, along with a pastoral network called Ekklesia.

The plan was for 9Marks to help Ekklesia tie together as many gospel-centered ministries as possible—and to throw a little gasoline on the conversations about biblical theology that were sparking around the country.

“In the beginning we had to give money to publishers to print books because nobody knew who Jonathan Leeman or David Helm was,” Aubakirov said. He joined Foote’s In Lumine Media and 9Marks in handing out Expositional Preaching: How We Speak God’s Word Today for free all over the region.

In his down time, he translated “about 150 core articles” into Russian and subtitled about 15 Ligonier/9Marks videos. He posted them on 9Marks Russian language site, but other gospel-centered sites were also growing—such as Ekklesia, the Samara training center, and Evangelical Christianity, which was started last year by two members of RBC. Since October 2011, the YouTube channel of Alexey Kolomiytsev, who preaches expositionally in Russian to a church of mostly immigrants in Washington state, has nearly 11.5 million views.

“By God’s grace, in that year and a half, 9Marks has become well-known among the pastors in Russia and Ukraine,” Aubakirov said. In 18 months, publishers had printed about 12 new 9Marks books in Russian; they plan to print another 10 this year, along with a couple in Ukrainian and Kazakh. Dever’s What Is a Healthy Church? Leeman’s Church Membership, Mack Stiles’s Evangelism, and Helm’s Expositional Preaching sold out within a year.

“I think if you ask an average pastor, they’ve heard of the brand and maybe read an article or book from 9Marks,” Aubakirov said. Through the International Mission Board, he ships three to five gospel-centered books every two months to 50 pastors in Ukraine, Russia, Kazakhstan, and Belarus—and he’s limited only by funding. When he announced the program in March, he received 200 applications from “pastors in villages where they can’t afford the books.”

After about a year, Ekklesia and 9Marks were able to send about a dozen key leaders from Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan to Capitol Hill Baptist Church’s training event. A few months later, an Ekklesia conference featuring Mark Dever drew 500 attendees.

In December 2018, Aubakirov wrapped up, moving back to Kazakhstan to pastor a small church there. “My mission was over,” he said. “This movement became a beast of itself.”

Double-Edged Growth

The quiet bubbling of gospel-centered theology over the last few years has been “a work of God,” Foote said.

“You can see a divine hand moving things around in order to get resources to people,” he said. “I wouldn’t say you could pinpoint one thing that triggered it, because you have all these organizations and people working separately to the same goal and finding each other eventually.”

9Marks international director Rick Denham, who has seen this pattern in the growth of Reformed theology in Brazil, expects “the Evangelical Christianity site to grow and be a broad voice. I also expect Ekklesia to continue to grow.”

That could bring trouble.

“The Russian government is initially tackling things that might be a political challenge,” Denham said. “The evangelical noise is so low right now that it’s not.” Get too much bigger, though, and it could be a target.

“As Reformed people who trust the sovereignty of God, we know he has a plan,” Foote said. “We can trust that when somebody gets elected who can take away our church freedoms, we can still trust God during that, and we should. Whatever God is allowing to happen, that’s what he thinks is good for the church at this time and place.”