Psalm 1 describes the image of the blessed man who is like a rooted tree. Because his “delight is in the law of the Lord,” this blessed man becomes “like a tree planted by the rivers of water, that bringeth forth his fruit in his season; his leaf also shall not wither; and whatsoever he doeth shall prosper.” This person draws sustenance from the Word of God and transforms its wisdom into fruit and leaves offered for the good of the community.

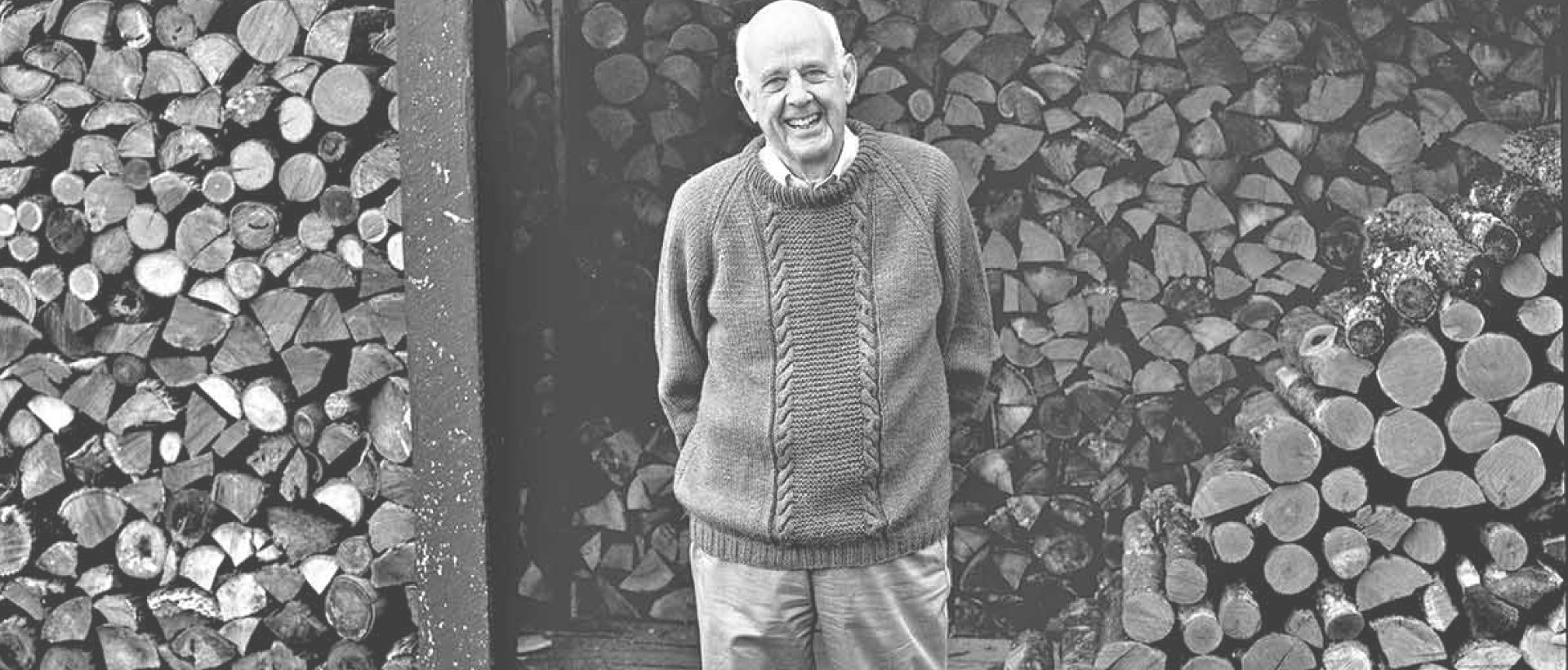

In one of his Sabbath poems, the Kentucky farmer and writer Wendell Berry inverts the psalmist’s image of the tree, nonetheless preserving its role as a mediator between God and a particular place. In describing his poetic role, Berry imagines himself as a tree planted not by a clear river, but “where gravity gathers / the waters, the poisons, the trash.” Yet his vision is marked by hope—hope that his writings might serve this diseased place in so far as they are inspired by the God who, as John tells us, is light (1 John 1:5):

He is a tree of a sort, rooted

in the dark, aspiring to the light,

dependent on both. His poems

are leavings, sheddings, gathered

from the light, as it has come,

and offered to the dark, which he believes

must shine with sight,

with light, dark only to him.

Berry figures himself as a tree whose leaves derive their sustenance from God, the Father of lights (James 1:17), and then offer themselves to their dark and damaged place, slowly restoring the soil’s fertility. Like the blessed man of Psalm 1, Berry seeks to ruminate on God’s Word so he can better serve the needs of his place and community.

Berry describes himself as a “marginal” Christian, and his position on the outskirts of our dominant, consumerist culture makes his a voice from the wilderness—one many evangelicals with more orthodox theology might do well to consider. Perhaps the greatest threat to the church today isn’t falling for doctrinal heresy but implicitly adopting the consumerist, self-centered assumptions of our Western culture. It’s all too easy for American Christians to assent to the right doctrines on Sunday while inhabiting a counter-Christian economy the rest of the week, loving ourselves more than God and neighbor.

Perhaps the greatest threat to the church today isn’t falling for doctrinal heresy but implicitly adopting the consumerist, self-centered assumptions of our Western culture.

Both Berry’s writings and his life challenge Christians to be rooted, fruit-bearing members of their communities—“to stand like slow growing trees / on a ruined place, renewing, enriching it.” This challenge is made most clearly in his Port William fiction, where broken, fallible characters work to embody Scripture in their daily lives. These stories act as parables, seeding our imaginations to consider redemptive ways of inhabiting our neighborhoods.

In what follows, we’ll look at some of Berry’s fictional characters who root themselves in both Scripture and place in order to practice the theological virtues of faith, hope, and charity.

Dorie Catlett’s Fidelity

Fidelity to place isn’t a characteristic American virtue. Our country’s pioneer past predisposes us to respond to difficult situations by moving on; we often want the option of a new place, a new church, a new spouse. Perhaps even more insidiously, even when we stay in a place, we often cordon ourselves off from the parts we don’t like. We eagerly latch onto various technologies of withdrawal, technologies that allow us to ignore uncomfortable problems.

One of Berry’s profoundly Christian characters, Dorie Catlett, embodies an alternative, faithful mode of living. In particular, she loves her wayward brother and continues to care for him despite the great pain he causes her. When her mother dies shortly after giving birth to a son, Dorie takes on the task of raising her brother. She nicknames him “Peach” and does her best by him, but as he grows up, his irresponsible drunkenness becomes a great burden on her and eventually her family. Nevertheless, in the same way that Jesus lives with the man he knows will betray him, Dorie refuses to cut herself off from a brother she no longer expects to change. Her commitment to Peach stems from Paul’s essential description of Christian love: “With exactly the love that ‘hopeth all things,’ she did not give up on him.”

Wheeler, Dorie’s son, is amused by his uncle’s escapades when he is a boy, but after he returns home with a law degree and a car, he “inherit[s] Uncle Peach, as an amusement but also as a responsibility and a burden.” When Uncle Peach is at the end of a long binge and calls for help, Wheeler goes to pick him up. He does his best to evade this responsibility, but “because he had the means of going, he had to go.”

Fidelity to place isn’t a characteristic American virtue. Our country’s pioneer past predisposes us to respond to difficult situations by moving on; we often want the option of a new place, a new church, a new spouse.

It’s amusing to read Wheeler’s stories of the things Peach says or does when drunk, but that’s because they remain safely on the page. It would be much less amusing if we were required to get out of our beds in the middle of the night to go fetch him from another drunken escapade, or to financially support him, or to share a family meal while listening to him brag about his exploits. In all of Wheeler’s stories about Uncle Peach, pain and humor and exasperation mingle inextricably; as Wheeler’s son Andy recalls, Wheeler “never spoke of Uncle Peach with unmixed feelings.”

When Uncle Peach dies, and the rest of the family are driving home from his funeral, Wheeler remarks wryly that “the preacher takes a very happy view of Uncle Peach’s prospects hereafter.” An uncomfortable silence follows, but Wheeler’s efforts to disentangle the complex meaning of Peach’s life provoke him to further explanation:

“If Uncle Peach is in Heaven, . . . and Lord knows I hope that’s where he is, then grace has lifted a mighty burden, and the preacher ought to have said so.” And then he said, as if determined in his impatience to capture every straying piece, “And as an earthly burden it wasn’t only grace that lifted it”—meaning it was a burden he too had borne.

Dorie had certainly felt the weight of Peach’s failings more acutely than had Wheeler, but she rejects her son’s self-pitying attitude, an attitude that feels unjustly put upon by his connection to Peach:

She said one syllable then that Andy later would know had meant at least four things: that his father would have done better to be quiet, that she too had borne that earthly burden and would forever bear it, that Uncle Peach had borne it himself and was loved and forgiven at least by her, and that it was past time for Wheeler to hush.

She said, “Hmh!”

Dorie’s whole life has been implicated in the life of her straying, frustrating, beloved brother, yet she doesn’t resent this burden or try to be free of it. Instead, she lives faithfully with it, hoping against hope for Peach’s redemption.

As Berry’s image of a tree planted in a polluted valley indicates, being rooted members of our places will involve us in pain and loss. Yet Dorie exemplifies how we might faithfully gather gifts from the light and offer them to the wounded people with whom we live.

As Berry’s image of a tree planted in a polluted valley indicates, being rooted members of our places will involve us in pain and loss. Yet Dorie exemplifies how we might faithfully gather gifts from the light and offer them to the wounded people with whom we live.

Andy Catlett’s Hope

Andy Catlett is the most autobiographical character in Berry’s Port William fiction, but one glaring difference sets Andy apart from his creator: Andy doesn’t have a right hand. He lost it while trying to unclog a corn picker. One of Berry’s recent stories, “Dismemberment,” describes how this machine, unable to tell the difference between a hand and an ear of corn, swallowed Andy’s hand “as the price of admission into the rapidly mechanizing world.” It’s in this way that, for all Andy’s criticisms of the mechanized world, his body is intimately marked by his complicity in it.

Why does Berry imagine the industrial economy marring Andy—and perhaps, in some parallel way, himself—in such dramatic fashion? Because living by its mechanistic structures obscures our fundamental membership in an economy of love. The word economy comes from the Greek work oikos, which means “household.” This is the same word from which we get ecology and even diocese. Indeed, Paul uses this Greek word in describing the church as “the household of God” (Eph. 2:19). Drawing on the apostle’s ecclesiology, Berry imagines creation as a household or economy held together by bonds of love. As he explains in an essay titled “Health Is Membership,”

I take literally the statement in the Gospel of John that God loves the world. I believe that the world was created and approved by love, that it subsists, coheres, and endures by love, and that, insofar as it is redeemable, it can be redeemed only by love. I believe that divine love, incarnate and indwelling in the world, summons the world always toward wholeness, which ultimately is reconciliation and atonement with God.

When we love others, and embody this love by work that meets their needs and fosters reconciliation, we participate in God’s sustaining love.

By obscuring our interdependence on others, however, our industrial economy obscures our participation in this divine economy. When we meet all our needs with the swipe of a card or the tap of a screen, we sever the taproot that anchors us in our places and communities. Through his right hand Andy enacted his membership in his place: it reached out to his wife; it held his pen; it grasped the reins; it mended his fences; it stroked his sheep. His complicity in the mechanized economy—symbolized vividly by the corn picker—threatened all these relationships, and the loss of his hand only made this threat more apparent.

When we meet all our needs with the swipe of a card or the tap of a screen, we sever the taproot that anchors us in our places and communities.

It took Andy a long time to recover from the loss of his hand and learn how to make do with an awkward left hand and a more awkward prosthetic. But he still felt dismembered from his community. When his friends and neighbors came to help him rake and bale the hay, he was “abashed because of his debility and his dependence.” But they just went to work, and by doing so, “they moved him to the margin of his difficulty and his self-absorption.”

When the hay was safely in the barn, Andy awkwardly thanked them, blurting, “I don’t know how I can ever repay you.” In reply, “Nathan gripped the hurt, the estranged arm of his friend and kinsman as if it were the commonest, most familiar object around. He looked straight at Andy and gave a little laugh. He said, ‘Help us.’” Andy’s help is certainly less effective than it used to be, but Nathan challenges him to stop letting his wound paralyze him.

As Andy heeds this call, going to work as best he can, he embodies his eschatological hope that one day he will be re-membered into God’s economy of love. One of the epigraphs to Remembering—Andy’s autobiographical account of his injury and restoration—is Ecclesiastes 9:4: “For to him that is joined to all the living there is hope.”

The Preacher’s rather spare, naturalistic hope takes a Christological turn in John 15, which Berry alludes to in “Dismemberment”: “I am the vine, ye are the branches: He that abideth in me, and I in him, the same bringeth forth much fruit: for without me ye can do nothing” (John 15:5). When we’re wounded, when we feel severed from our communities and the body of Christ, allowing ourselves to be helped and then going to work meeting the needs of others mends these fractured memberships. Such work re-roots us in our places and enacts our hope for God’s final redemption.

Sustaining healthy households and working in the economy of love have always been hard. In an industrial economy, there are many structural and personal impediments—it can feel like we’re working with only one hand—but we can still put our bodies to work meeting the physical and spiritual needs of our neighbors.

We can swap work with neighbors, we can grow a garden and share its produce, we can cook a meal for our families and invite friends to share it, we can play with children and listen to the elderly. When we do these things in Christ’s love, we embody our hope in the reconciling work of the God who so loves his world.

Tol Proudfoot and Nightlife’s Charity

The economy of love includes us in membership with our neighbors—even those who test our love for them. Berry’s story “Watch with Me,” which explores this difficult work of love, is shaped by two passages in Matthew’s Gospel: Christ’s suffering in Gethsemane and his parable of the lost sheep. By the end of the story, we’re led to consider what it means to love our neighbors, particularly those whose lostness requires us to watch them with Christ’s sacrificial love.

At the heart of this story are three loves—the abiding, neighborly love of “Tol” Proudfoot, the long-suffering charity of “Nightlife” Hample, and the perfect love of Christ that contains both Tol and Nightlife’s loves. Tol is one of Port William’s more loving and lovable characters; a large man who likes a good story, his disposition is tender and gracious. Nightlife is on the margins and earns his nickname because he lives in physical and mental darkness. With poor vision, he wears thick glasses and suffers from intermittent bouts of mental illness that leave him lost to the world around him.

When Nightlife is so lost, his mind would get

a leak in it somewhere, some little hole through which now and again would pour the whole darkness of the darkest night—so instead of walking in the country he knew and among his kinfolks and neighbors, he would be afoot in a limitless and undivided universe, completely dark, inhabited only by himself.

“Watch with Me” recalls how Tol and some other neighbors follow Nightlife on a long journey through the woods while he suffers from one of these spells—on this occasion, however, he’s a threat to himself and to the others because he has calmly taken Tol’s shotgun and proclaimed that “a damned fellow just as well shoot hisself, I reckon.” The night before he snatches the gun he had wanted to give a sermon at Goforth Church about “what it was like to be himself,” but the preachers refused to allow him to speak.

Gun in hand, Nightlife heads off into the woods, leading Tol and the others on a circuitous journey through day and night as they attempt to contain Nightlife in a “moving room” of protection. Yet despite the neighbors’ love for Nightlife—a love that puts their own lives at risk—they fail to contain him. And like the lost sheep of Matthew 18, Nightlife eventually eludes the men in the dark woods.

Reading Wendell Berry reminds us that one result of rooting ourselves in the Word of God should be that we root ourselves in our neighborhoods.

Having lost their purpose the men eventually drift off to sleep, only to be awoken by Nightlife who has returned and is standing near the remnants of the fire. He speaks to them: “Couldn’t you stay awake? Couldn’t you stay awake?” A third and fourth time he asks them in their bewilderment, “Couldn’t you stay awake?” Nightlife is like Christ, in his great anguish, asking his disciples to “watch with me,” only to find them sleeping.

Nightlife goes on, stepping out of the circle of men, leading them through the woods and the darkness and into a new day, arriving back at Tol’s barn where the journey began. Once in the barn, Nightlife preaches to his captive audience the sermon that the revival preachers had silenced. His text is Matthew 18:12—the parable of the lost sheep—which he knows by heart. As they listen to him, Tol and the men begin to understand that their love for Nightlife has fallen short.

Though they tried to contain him in their love and protection during his spell, they have failed to imagine the depths of his suffering. And this is because they’re among the 99. Nightlife doesn’t need them to contain him—he needs them to understand what it’s like to be him, to be the one lost sheep:

Nightlife understood [the parable] entirely from the viewpoint of the lost sheep, who could imagine fully the condition of being lost and even the hope of rescue, but could not imagine the rescue itself.

The Port William community can’t fix Nightlife, no matter how much they try to contain him or put him back together; they can only abide with him, watch with him, when he suffers alone in darkness. “Oh, it’s a dark place, my brethren,” Nightlife says. “It’s a dark place where the lost sheep tries to find his way, and can’t. . . . [T]he shepherd comes a-looking and a-calling to his lost sheep, and the sheep knows the shepherd’s voice and he wants to go to it, but he can’t find the path, and he can’t make it.” The men hear Nightlife’s sermon and are moved. They’ve come into a sort of knowledge of his suffering, “what it was to be him.” After his sermon, Nightlife emerges from the shadowland of his own mind, giving the shotgun back to Tol, and their entire ordeal ends with a shared feast.

By placing Christ’s own terrible words at Gethsemane in the mouth of Nightlife, Berry unites their suffering and reminds us that Christ loves the weak and wandering. The light in the darkness of this world is that there is a Love that contains all of us, even the lost sheep. And those of us who are among the 99 would do well to learn from this story that we might be called on to risk our own well-being to recover a lost sheep. Nightlife teaches us to love the least among us, those we don’t understand, those whose suffering is foreign to us. And this love may simply be our presence—that we watch with them. We can share meals with neighbors who annoy or exasperate us, listen to their voices without condemnation, shovel their driveways despite their politics, and teach our children to do the same. Perhaps by so doing, we participate in the love of the God who became lost so that all might be found.

Reading Wendell Berry reminds us that one result of rooting ourselves in God’s Word should be that we root ourselves in our neighborhoods. These places are likely to be dark and polluted, but in belonging here while stretching toward the light of God’s love, we bear witness to John’s proclamation: “The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it” (John 1:5). Berry’s fictional characters help us imagine what it might look like to be members of God’s household who live with faith, hope, and love—and so bless their neighbors.

Related Articles:

- Wendell Berry and the Beauty of Membership (Matt McCullough)

- Finding Our Place: Our Family’s Long Quest for Calling and Home (Hannah Anderson)

- Look & See: A Portrait of Wendell Berry (Justin Taylor)

- Wendell Berry and the Revitalized Pastor (Paul House)

- 5 Ways Wendell Berry Is Making Me a Better Pastor (Andrew Shanks)

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.