This article is part of TGC’s longform series. We pray that in an age of lots of noise, this series will help equip, inform, and encourage you to live as disciples of Christ.

It seems revivals have fallen on hard times. Revivals today are associated with Pelagianism, American individualism, and kooks on cable television. Many find these associations distasteful, especially young Reformed folks who identify deeply with Reformation theology while turning a suspicious eye to revivals’ emotionalism.

Thus, while many appreciate Jonathan Edwards, George Whitefield, and the First Great Awakening, they almost invariably write off later American revivals as hotbeds of human activism, heresy, cults of personality, and emotional extravagance. Better to leave all that in the dustbin and get on with the mission of preaching the gospel and building the church. Right?

There are some good theological instincts at work here, but also quite a few historical inaccuracies. For one thing, revivalists haven’t always been non-theological pragmatists. From about 1740 to 1840, the church’s greatest minds thought seriously about revival—how conversion works, how the gospel should be preached, and how soteriology is manifested practically. I wrote about this time in my recent book, Theologies of the American Revivalists: From Whitefield to Finney.

Some critics of revival believe that revivalism is alien to the essence of Protestantism; that Protestants, through their participation in the Awakenings, got sidetracked by the Enlightenment, religious fanaticism, modernity, individualism, or some mixture of the above. It’s true that the Awakenings—those great revivals of the 18th and 19th centuries in America—helped create that vague grouping of conversionistic Protestants known as “evangelicals.” But the idea that evangelicalism, and the revivals that spawned it, represent a warping of the spirit of Protestantism is a historical stretch.

I advance the opposite thesis: Revivals embody the true flourishing of Protestantism precisely because they intensify and expand on central Protestant themes. When evangelicalism emerged from its Protestant background through the Great Awakenings, it carried forward some of the best features Protestantism had to offer the world.

Revivals embody the true flourishing of Protestantism precisely because they intensify and expand on central Protestant themes.

There are many continuities between Reformation Protestantism and revivalistic evangelicalism, such as emphases on preaching, conversion, and mission. The revivals intensified and expanded these three emphases, creating something new (evangelicalism) while simultaneously retaining deep ties with the Reformation.

Preaching

Both Reformation Protestants and Great Awakening evangelicals underscored the centrality of proclaiming the Bible. The Zurich reformer Ulrich Zwingli pioneered expository preaching due to his conviction that God’s Word needed to be preached in its entirety to God’s people. The very architecture of Reformation-era churches prioritizes the Word: pulpits are central so attention is drawn naturally to the preacher.

American revivalists shared this attitude toward Scripture. They also preached the same fundamental message: Don’t trust in your own works but believe in the Lord Jesus Christ and you shall be saved. In short, sola scriptura and sola fide were fundamental hallmarks of both the Reformation and the American revivals. At the same time, the revivals intensified several themes in preaching that yielded something new. Here are three.

1. Emotional Intensity

First, while there had always been animated preaching, Awakening preaching generally took the emotional intensity of an evangelistic message up several notches, dramatically portraying the plight of the sinner, the wrath of God, and the necessity of new birth.

Some of these sermons have become legendary. Most of us are familiar with Jonathan Edwards and the spider: “The God that holds you over the pit of hell, much as one holds a spider, or some loathsome insect, over a fire, abhors you, and is dreadfully provoked.” Others haven’t entered evangelical historical memory but were equally powerful. Take for example the closing of a sermon by Albert Barnes (1798–1870), the New School Presbyterian from Philadelphia:

You know your duty, and your doom, if you do it not. . . . [I]f you will perish, I must sit down and weep as I see you glide to the lake of death. Yet I cannot see you take that dread[ed] plunge—see you die, die forever, without once more assuring you that the offer of the gospel is freely made to you. While you linger this side the fatal verge, that shall close life, and hope, and happiness, I would once more lift up my voice and say, See, sinner, see a God of love. He comes to you. . . . To him I commend you, with the deep feeling in my own bosom, that you are in his hands; that you are solemnly bound to repent today, and believe the gospel, and that if you perish, you only will be to blame.

Both examples illustrate the powerful rhetorical techniques that American revivalists cultivated in the Awakenings, techniques still heard in American pulpits today.

2. The Subject of Preaching

Second, the subject of preaching was transformed during the great revivals. Before the Awakenings, Reformation sermons focused on pronouncing the full counsel of God, either through expositional preaching or the more topical “plain style” employed by the Puritans.

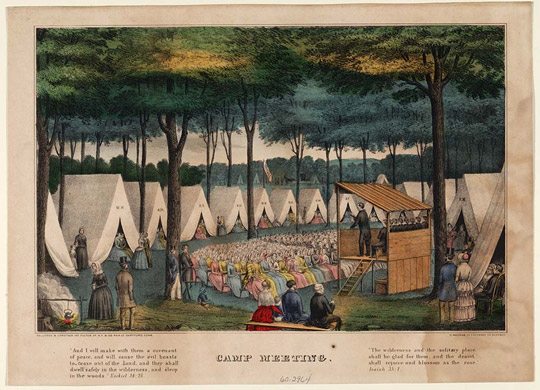

These styles survived the Awakenings, especially in weekly church services, but the Awakenings featured another style of preaching that has become the hallmark of evangelical proclamation—that of an itinerant evangelist focused exclusively on evangelistic themes: sin, God’s wrath, Christ’s atoning work, justification, and the necessity of the new birth. Rather than seeking the edification of the saints, this preaching was much more targeted toward the conversion of the lost.

3. Great Gospel Communicators

Third, the Awakenings transformed preaching by drawing attention to great gospel communicators. When George Whitefield began his spectacular preaching ministry, he left an indelible stamp on the evangelical psyche: the image of a powerful, dramatic preacher who preached exclusively on evangelistic themes, without notes, to large crowds who came flocking to hear him. Families, churches, and communities were all transformed by his preaching. All of this spawned a new clerical identity: the itinerant evangelist.

Whitefield wasn’t alone; other great preachers began itinerant ministries as well—John Wesley in England, Howell Harris in Wales, and Gilbert Tennent, Samuel Davies, and Jonathan Edwards in the American colonies. Pretty soon the Protestant world was traversed by itinerant ministers preaching the gospel and seeking the conversion of the lost. Evangelicals ever since have identified with major itinerant evangelists: Wesley, Nettleton, Finney, Moody, Sunday, and Graham.

The Great Awakenings transformed Reformation preaching into an intensely emotional experience, focused exclusively on an evangelistic message, and heralded by an outstanding preacher. So while evangelical preaching continued the Reformation tradition of preaching God’s Word, the preaching that emerged in the wake of the revivals had changed dramatically.

The Great Awakenings transformed Reformation preaching into an intensely emotional experience, focused exclusively on an evangelistic message, and heralded by an outstanding preacher.

Was this a negative change, severing evangelicals from their Reformation heritage by leading them to idolize dynamic preacher-communicators? Did it lead pastors and evangelists to become entertainers peddling a watered-down version of the gospel? No; these fears are a caricature of revival gone haywire, a distortion of good and true revival preaching.

There will always be bad apples in the evangelical fold, but we shouldn’t abandon evangelical essentials because of them. With moderation, each change surveyed here can be harnessed for improved Christian ministry. Preaching should be animated to a degree, because the Word of God is living and active. Gospel-centered sermons, as well as expository sermons concluding with a brief summons to repentance and faith in Christ, should be commonplace in our churches, for they remind us of our gospel foundation and our obligation to evangelize. And the church should always encourage and support its gifted evangelists. We can be grateful for the ways the Awakenings transformed Protestant preaching.

Conversion

Long before the rise of evangelicalism, Protestant reformers understood that Christians weren’t just born; they had to own the faith. The faith of their church, state, or parents didn’t cut it. The Christian, as Luther noted, must live coram deo or “before the face of God”; no one else can do this for her.

Further, because the reformers taught that we enter the world with original sin, none of us is naturally inclined to believe, much less live a life of faith. That transformation must come later. Thus, while Reformation Protestantism arose in a context where state-sponsored religion and catechesis were commonplace, the seeds of a later conversionism were already present.

Similarly, the English Puritan, Dutch Reformed, and German Pietists all had theologies of a pre-conversion soul struggle designed to prepare sinners for faith in Christ by weaning them from self-reliance and works-righteousness. While many underwent a mild and short-lived period of spiritual unease prior to belief, others experienced a protracted season of guilt and conviction before discovering the way of faith.

Many are familiar with Luther’s great struggles with guilt prior to his conversion. But he wasn’t alone. Many of the Puritans and Pietists, such as John Bunyan, John Owen, and August Francke, experienced profound periods of conviction prior to gospel faith. In fact, so central was this experience that for a brief time the young Jonathan Edwards feared he’d missed God’s grace since he hadn’t experienced the “terrors” that were supposed to precede true conversion. Dramatic, experiential conversions aren’t a modern invention; they have their roots deep in Protestant history and theology.

1. Intensely Emotional Conversions

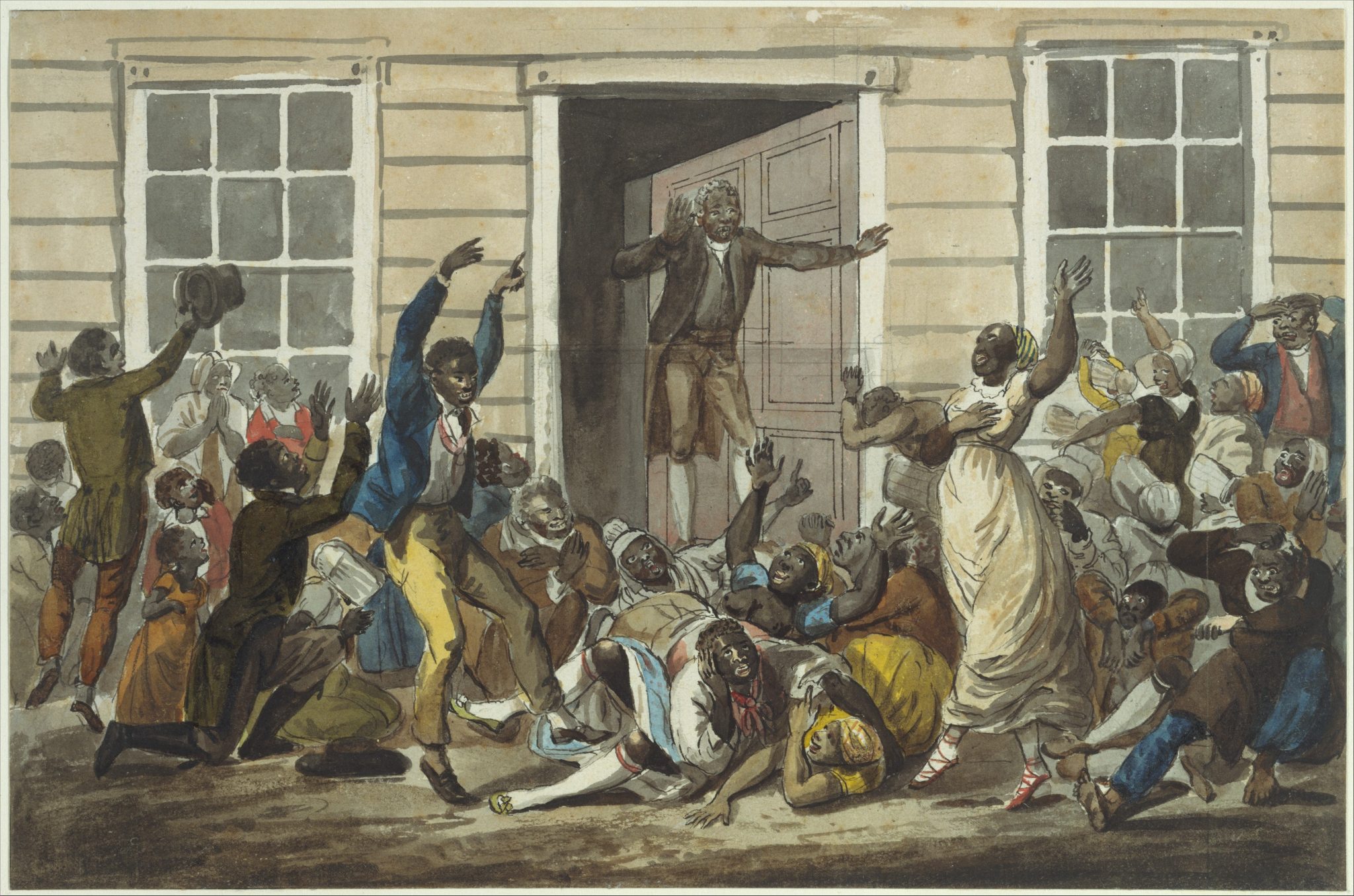

But the Awakenings did intensify the standard evangelical conversion experience. Extremely emotional conversion experiences became more prominent. To be sure, many still experienced gradual conversions as they were raised in Christian environments and catechized by believing parents, coming to a point where repentance and belief wasn’t a major struggle. But in the First Great Awakening we see an increase in powerfully dramatic conversions.

For instance, the missionary David Brainerd experienced an intense and protracted period of spiritual distress leading up to his conversion in 1739: “I thought the Spirit of God had quite left me. . . . [I was] disconsolate, as if there was nothing in heaven or earth could make me happy.” Yet during a prayer walk, something unexpected happened to him:

Unspeakable glory seemed to open to the view and apprehension of my soul. . . . I stood still, wondered and admired! I knew that I never had seen before anything comparable to it for excellence and beauty; it was widely different from all the conceptions that ever I had of God, or things divine.

God opened Brainerd’s spiritual eyes, enabling him to see the light of God’s glory in the face of Jesus Christ (2 Cor. 4:6).

Ann Hasseltine—a young Massachusetts woman who later became a missionary—felt her “heart began to rise in rebellion against God” prior to conversion in 1807. She believed God had no “right to call one [to salvation] and leave another to perish.” She hated God’s holiness so much that “I felt, that if [I was] admitted into heaven, with the feeling I then had, I should be as miserable as I could be in hell. In this state I longed for annihilation.”

Yet she sought the Lord for a new heart and discovered a “new beauty in the way of salvation by Christ,” one that freed her from her fears and set her on a life of selfless service. Stories like Brainerd’s and Hasseltine’s became common during the Great Awakenings as dramatic, datable conversion experiences became the norm.

2. Shorter Conversions

Conversion experiences also became shorter. Conversion experiences in the First Great Awakening often took several days or weeks, since pastors tested conversions for authenticity. Would-be converts also waited to discern signs of a new heart (love for God and other fruits of the Spirit) before they recognized their conversion as genuine.

By 1800, however, due to the rise of Arminianism, conversion became more associated with an act of will. Arminianism put greater emphasis on human choice in the salvation process. It also emerged out of Edwardsean Calvinism, which emphasized the sinner’s natural ability to choose Christ in spite of his moral inability to do so, categories found in Edwards’s classic treatise Freedom of the Will. Because of this shift in emphasis, it became easier to identify a conversion by an act of the will, such as a commitment to follow Christ. Identifying mature fruits of the Spirit wasn’t necessary.

What are we to make of these shifts in evangelical conversions? First, advocates of every kind of conversion agreed that, theologically, regeneration is an instantaenous work of God. The variability in experience arises from historical, social, and personal factors. People are different, and they’ll experience conversion in diverse ways.

Second, we shouldn’t interpret the shift to shorter conversions only as the result of Arminianism or Pelagianism. It’s true Arminianism was becoming increasingly popular in America by 1800, and it’s true some evangelicals, untutored in historical theology, articulated their soteriology in Pelagian terms. But as we saw above, the story is more complex: New England Calvinists also incorporated “willing” as a central component of their soteriology. After all, they reasoned, a person is converted when one has believed, trusted, or placed faith in Christ—all acts of the will.

Ultimately, willing in the salvation process wasn’t the central issue; willing for the proper reasons was. How can we discern if someone has believed for the right reasons (i.e., love for God) rather than selfish ones? Edwards reflected on this question at length in The Religious Affections. He maintained that the greatest indicator of true conversion is not a certain kind of willing, nor undergoing a specific kind of conversion experience. Rather “Christian practice”—or humble demonstration of the fruit of the Spirit—is the key indicator of conversion. Christian practice “is the chief of all the signs of grace,” he wrote, “both as an evidence of the sincerity of professors unto others, and also to their own consciences.”

Missions

In missions we see the least continuity between 16th- and 17th-century Protestants and evangelicals of the First and Second Great Awakenings. There was indeed missionary activity among Protestants prior to the First Great Awakening. Both the New England Puritan John Elliot—who ministered among the Massachusett Indians—and the German Pietists—who sent missionaries to Asia, Africa, and North America—come to mind. But more often than not, the reformers’ energies were directed toward constructing an orthodox and godly Christian society. Their mission was to their immediate societies, and not so much to the ends of the earth.

It wasn’t until 1780 to 1830 that we see a dramatic increase in evangelical missionary activism, both in America and Great Britain. This was the age of famous missionaries like William Carey and Adoniram and Ann Judson, as well as great missionary-sending societies like the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions and the London and Baptist Missionary Societies.

Why did it take until the 19th century before a serious missions-mindedness gripped evangelicalism? The answer is complex.

Why didn’t a serious missions-mindedness grip evangelicalism before the 19th century? The answer is complex. First, it wasn’t until the turn of the 19th century that Western colonialism and imperialism developed to the point where conditions were ripe for the flourishing of missionary endeavors abroad. By 1800, Western Europe and America were in the midst of the first great wave of the commercial and industrial revolutions. These required sophisticated transportation networks as well as a Western presence in many of the cultures around the world.

While we rightly lament the great evils committed by Westerners who exploited the world’s populations and resources, it’s also true that, in the midst of Western expansion, Christians achieved a degree of access to the far corners of the earth they likely wouldn’t have had otherwise. History is full of contradictions and mixed blessings. Western expansion was indeed one of these, yet one of its positives outcomes was that it further enabled the spread of the gospel throughout the world.

Second, because of the rise in evangelical conversions during the Second Great Awakening, financial giving to missionary activities surged in the early decades of the 19th century. Membership in evangelical denominations in America swelled dramatically in the early 1800s, a result of the ministry of hundreds of evangelists, revivalists, and pastors who tirelessly preached the gospel. These converts, in turn, began selflessly funding the missionary agencies, leading to a rise in missionary activity among evangelicals.

Last, there was a significant increase in voluntary ministerial efforts by evangelicals both in America and Great Britain in the early 19th century. For numerous reasons, American evangelical laypersons channeled their energies and resources into parachurch ministries: orphanages, poverty relief, temperance, Bible societies, and both home and foreign missions.

In short, these historical realities—an existing transportation network, a Western presence throughout much of the world, and evangelicals willing to give of time and resources to gospel causes—profoundly expanded missionary activity in the 19th century. This in turn launched the great century of missions.

Refined Evangelicalism

The world has gotten a lot smaller in the past 200 years. In spite of our many faults, evangelicals have managed to take the gospel to the far reaches of the earth. As I’ve tried to argue here, the transition from reforming Protestantism to evangelicalism through the Great Awakenings has been, on the whole, a positive one. Overall, it has refined us, enabling us to do what we do best: preach the Word, lead sinners to Christ, and mobilize our resources to reach the ends of the earth with the gospel.

As long as we remain vigilant against the forces of modernity, infidelity, and worldliness, and devote ourselves to the task of exalting Christ through gospel ministry, we will, by God’s blessing, continue on through the economic, political, and social changes that are coming. And who knows? God may in the midst of this bring about another Great Awakening. After all, he “is able to do far more abundantly than all that we ask or think” (Eph. 3:20).

Other entries in this series:

- Finding Our Place: Our Family’s Long Quest for Calling and Home (Hannah Anderson)

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.