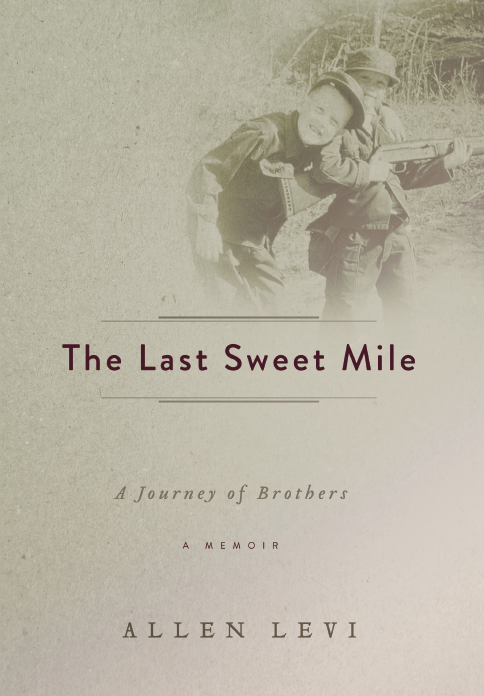

When Allen Levi’s brother Gary was diagnosed with inoperable brain cancer, neither realized they were about to embark on the best year of their lives. More than brothers, Allen and Gary were best friends, lifelong bachelors—one a lawyer turned singer-songwriter, the other a globe-trotting missions worker. Their relationship was one of rare and powerful beauty, and in this excerpt from his book The Last Sweet Mile (Rabbit Room Press), Allen pulls back the veil on one of the hardest days of that year—the day he laid his brother to rest. In doing so he demonstrates the power of affection, community, and defiance in the face of death.

Three decades ago, Dad moved a small white chapel from Suggsville, Alabama, near Mobile, to the northeast corner of the pasture at the farm. His maternal ancestors had been members of the congregation who first met in that chapel when it was built in 1806. Dad had recently come to Christ, the last in our family to do so, and wanted to build something on the property that was a visible expression of his and the family’s faith in God. He also wanted it to be a place in which we, the family, might celebrate special occasions.

Over the years, it has been the place Dad had hoped it might be for us, but it has also been the site of weddings, celebrations, concerts, and assorted other events for our friends and community.

A Place to Be Buried

A few years ago, long before my brother Gary got sick, Dad told us that he’d like to be buried there. An antique wrought-iron fence—I’m not sure where it came from—was placed around a 25-foot-by-25-foot square section of ground on the east side of the chapel.

A few weeks before Gary passed away—on a pleasant, almost cool Saturday summer morning—25 or so men from the weekly front-porch gathering came together at the chapel to perform a peculiar kindness. They were there at the invitation, and with the blessing, of our family.

They assembled just after sunrise, shovels in hand, to cut a hole in the dense but, thankfully, rain-soaked Georgia clay. They had come to prepare the place where Gary’s body would be laid to rest.

They worked in pairs, each twosome digging enough soil to fill a wheelbarrow and then pushing it away to make room for the next team—assembly-line gravediggers if you will. There was laughter and conversation. There was perspiration and deep breath. There were tears. There was gladness and a deep sense of purpose to the morning’s labor.

I was fortunate to be with them.

Acts of Labor

Before the digging began, we gathered inside the chapel to pray and talk about the task before us. It was agreed that our labor that day would demonstrate three things: an act of affection, an act of community, and an act of defiance.

An act of affection. A visible, practical gift to our family, as if to say, “Someone, at some point in the near future, is going to have to do this difficult thing. We’d like to do it because we can do it with a love and with a purpose no hired hand could possibly bring to the task. We have so wanted to prove ourselves useful to you over the past months. Let our hands be the ones that break this ground.”

All of those present that morning knew and loved Gary. Most had known him for years. All had benefited from his influence in their lives. Some were his “children in the faith.” When they first heard the news of his illness, these same men had wept unashamedly, prayed fervently, and spoken unreservedly about their indebtedness to my brother. And on that Saturday morning, while believing in the miraculous but resigned to the likely, they dirtied their hands and feet to prepare a place for his body. And a mighty fine place it was when all was said and done, precise and orderly and clean, 40 inches wide, 48 inches deep, 96 inches long.

An act of community. Anyone knows there are easier, quicker, more efficient ways than hand-shoveling to dig a hole in the hard Georgia clay. There are diesel-powered machines that do the work well, for instance. One person on such a machine, impersonal and detached, can get the job done in very little time and with little or no sweat. But these brethren were of the belief that there is something holy about working side by side. And especially for an undertaking like this one, the involvement of the group was an affirmation that the passing of this brother would not be just a private loss but a communal one. There was something sacred about those shovels full of clay.

An act of defiance. Someone read a Scripture to start the day:

Since the children have flesh and blood, [Jesus] too shared in their humanity so that by his death he might break the power of him who holds the power of death—that is, the devil—and free those who all their lives were held in slavery by their fear of death. (Heb. 2:14–15)

Some, I suppose, might think that ours was a morbid task, one better left to the morticians and their paid crews. For us, though, the doing of it allowed us to quietly declare that we will not live as slaves to our fear of dying. Any death, and particularly this one, is unwelcome and unnatural. It still makes us uneasy and afraid, but our work that day was a taunt to the one who would have us live in abject terror of our mortality. We each stood in that grave and thrust our shovels into its heart as if to say, “Death, we will not be afraid of you. Where is your victory? Where is your sting? Have you not heard of Jesus? Have you forgotten his cross? Have you forgotten his empty tomb? Do you think we have forgotten it? Poor death. You poor, pitiful thing.”

Some, I suppose, might think that ours was a morbid task, one better left to the morticians and their paid crews. For us, though, the doing of it allowed us to quietly declare that we will not live as slaves to our fear of dying. Any death, and particularly this one, is unwelcome and unnatural. It still makes us uneasy and afraid, but our work that day was a taunt to the one who would have us live in abject terror of our mortality. We each stood in that grave and thrust our shovels into its heart as if to say, “Death, we will not be afraid of you. Where is your victory? Where is your sting? Have you not heard of Jesus? Have you forgotten his cross? Have you forgotten his empty tomb? Do you think we have forgotten it? Poor death. You poor, pitiful thing.”

Affection, community, defiance—those ingredients make for a good day. And a good day it was. It reminded each of us that our bodies too will return to the earth by and by.

The Most Preferable Death

When Gary was first diagnosed with a brain tumor, and after he agreed to seek medical care, we had to choose, as a family, what kind of treatment he should receive and where. Our options were many, but early on, with Gary’s blessing, the decision was made to keep him close to home in the belief that the best medicine—or most preferable death—was that which allowed for the constant nearness of people who knew and loved him. By that decision, we were assured that the last thing Gary would feel, hear, or sense in this world would be the tenderness, reverence, and adoration of those to whom he meant most; in other words, he would leave this world feeling the same things, though to a lesser degree, that he would feel when he took his first breath on the other side.

On the evening of the grave-digging, I sent this note to the men:

Saturday evening, June 16, 2012, 9:35 p.m.

Dear Brethren,

Words fail me, but I didn’t want the day to end without at least trying to express my thanks to you for your work this morning. How blessed we are, and how heartily can we say with the psalmist, “The boundary lines have fallen for [us] in pleasant places.”

I went back to the cemetery this evening by myself. It looked and felt quite different than it did when we were all together there earlier today. This morning there was activity, conversation, and camaraderie. This evening it was stillness, quiet, and solitude. Standing there alone made me grateful that my memories of the place will always include the sight of friends working side by side, the sounds of laughter and lightheartedness, and a sense of belonging that is bigger than any one of us. Knowing that your footprints are in and around the spot where Gary’s body will be laid to rest is a comforting thought, and I’m sure he’d be happy to know that you and I had a hand in preparing it.

It is such a gift to follow Christ and to walk through life with men like you. Thank you for sharing your time with me, not just today, but weekly. I am honored, and I am your debtor.

— Allen

Gary passed away early on a Sunday morning.

Finished Work

On Tuesday of that week, we had a private burial at the farm—just family—and then a public memorial later that afternoon. By day’s end, one task remained undone. Gary’s casket had been placed in the ground but left uncovered.

Two days later, at 7:00 a.m., just after sunrise, instead of meeting at my house on the porch as we usually did on Thursday mornings, the brethren gathered at the chapel, shovels in hand, to mend the earth and close Gary’s grave.

It was a beautiful morning.

We sang a song.

We read and talked about John 21.

We moved the soil back to its place.

We said goodbye.

Our work was done.

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.