Several years ago, Abby and her father, a Chinese immigrant with broken English, went to a convenience store because he needed to copy some documents. When he couldn’t get the copier to work, he tried to explain his problem to the owner of the store.

Instead of helping him, though, the owner mocked him, ripped up his papers, and told him to leave. Abby, who was then only 7 or 8, remembers:

I had always known my father as strong, kind, and smart. I had never seen him humiliated like that in front of me. He was so ashamed—I was so ashamed. I didn’t know what racism was before that day, and what it could do to someone—but after that, I knew.

This is what vulnerability without authority looks like. And it’s one of the stories Andy Crouch—executive editor of Christianity Today—tells to illustrate suffering in his new book, Strong and Weak: Embracing a Life of Love, Risk, and True Flourishing.

Paradox of Flourishing

Each of us wants to flourish, not suffer. We want abundant, generous, and full lives. We want our words and actions to mean something in the world.

Yet we often don’t know how to get there. After all, many of us don’t know what we’re meant to be or, if we do, why there’s a gap between our hopes and our realities.

In Strong and Weak, Crouch gives language to our struggle and surprises us with a refreshingly nuanced view of flourishing, which he says doesn’t come from being just strong. The paradox is that it comes from being both strong and weak in equal measure.

Strong and Weak: Embracing a Life of Love, Risk, and True Flourishing

Andy Crouch

Strong and Weak: Embracing a Life of Love, Risk, and True Flourishing

Andy Crouch

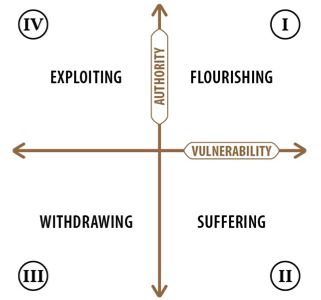

To help us grasp the nature of this paradox, Crouch introduces a 2 x 2 chart formed by two axes—authority and vulnerability.

The vertical axis is authority, which Crouch defines as the capacity for meaningful action. It’s about how much we can make a difference in our world. It’s “meant to characterize every image bearer,” Crouch argues, because it’s a part of what being given “dominion” over creation means.

The horizontal axis is vulnerability, which Crouch describes as exposure to meaningful risk. “The vulnerability that leads to flourishing,” Crouch says, “requires risk, which is the possibility of loss—the chance that when we act, we will lose something we value.”

Four Quadrants

Properly combined, authority and vulnerability lead “up and to the right” to flourishing (I)—that is, to “abundant life” (John 10:10), the “life that really is life” (1 Tim. 6:19). It’s engagement, hope, and dignity. It’s “what love longs to be.”

This type of flourishing, however, is not synonymous with health, wealth, growth, and gentrification. Those are mere images of a prosperity gospel in a consumerist society. The real test of human flourishing, he contends, is “how it cares for the most vulnerable.”

This type of flourishing, however, is not synonymous with health, wealth, growth, and gentrification. Those are mere images of a prosperity gospel in a consumerist society. The real test of human flourishing, he contends, is “how it cares for the most vulnerable.”

When either authority or vulnerability is absent—or even worse, when both are missing—we find distortions: suffering, withdrawing, and exploiting.

Suffering (II) is vulnerability without authority. It has no capacity for meaningful action but great exposure to meaningful risk. All of us, like Abby, will one day live in this quadrant and feel its poverty, deprivation, and oppression—whether it comes through loss, injustice, or death.

Withdrawing (III) is no authority or vulnerability. It’s “the worst of all,” Crouch says, because it masks itself as comfort or safety, but it’s really abandonment, apathy, and fear of exposure. As Crouch shows, our culture loves to withdraw by embracing simulated authority and illusory vulnerability—from pornography to gaming.

Exploiting (IV) is authority without vulnerability. It’s “the most seductive and dangerous quadrant,” Crouch cautions. It lures us with coping mechanisms that tell us we’re in control, as we shed our own vulnerability and exploit others. This section is particularly poignant for those who care about issues of injustice, policing, and race, which Crouch addresses directly and humbly.

Way to Flourishing

The paradox of flourishing, though, isn’t just about being strong and weak. In fact, the real genius of the book is the counterintuitive path Crouch says we must walk to get there:

Surprisingly, rather than simply moving pleasantly into ever greater authority and ever greater vulnerability, we have to take two fearsome journeys, both of which seam like detours that lead away from the prime quadrant. The first is the journey to hidden vulnerability, the willingness to bear burdens and expose ourselves to risks that no one else can fully see or understand. The second is sacrifice, the choice to visit the most broken corners of the world and our own heart.

These sections—hidden vulnerability and descending to the dead—will make you weep at the thought of your own sinfulness and the beauty of the gospel. You’ll see why you need to make these two journeys, so that you can understand the danger of worshiping idols of power and influence, the temptation of becoming a tyrant yourself, and the drift toward embracing hypocrisy.

Leaders—from executives to teachers to parents to writers—will find the concept of hidden vulnerability particularly compelling. Finally, someone understands, you’ll say to yourself as you read why being a leader means remaining silent about your own vulnerabilities, sharing them with only a small group. Yet you’ll feel challenged when you see how you must also bear your community’s shared vulnerabilities.

Gospel Center

Apart from its easy prose, vivid stories, and keen insights, Strong and Weak is beautiful because it drives toward the gospel. Crouch masterfully shows Jesus is the one person who held this elusive paradox in tandem—full authority and full vulnerability—for the sake of those he loved:

His authority was evident to everyone—at every turn of the Gospel narratives we see Jesus exercising unparalleled capacity for meaningful action, as well as restoring authority to the marginal and poor.

But no one fully grasped Jesus’s vulnerability. Those around him comprehended almost nothing of his true purpose and destination. The Gospel writers report that even when Jesus began to try to explain to his disciples the fate he knew awaited him in Jerusalem, they resisted and did not understand. As his ministry brought him nearer and nearer to the final confrontation with the forces of idolatry and injustice, only Jesus understood what was truly going to be lost.

It’s possible to come away from Crouch’s first book, Culture Making, thinking that being an image bearer means making culture—that is, having authority over creation. After reading Strong and Weak, however, it’s impossible to conclude being made in God’s image is anything other than both exercising authority and embracing vulnerability.

May we be a people who are both strong and weak for the sake of God’s glory and for the flourishing of ourselves and others.