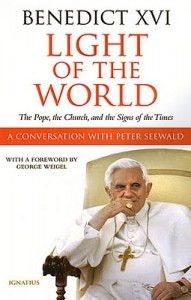

I recently read through the Q&A with Pope Benedict, an interview published as Light of the World: The Pope, The Church and The Signs Of The Times. I highlighted several sections and would like to share them here (along with some corresponding thoughts of my own).

I recently read through the Q&A with Pope Benedict, an interview published as Light of the World: The Pope, The Church and The Signs Of The Times. I highlighted several sections and would like to share them here (along with some corresponding thoughts of my own).

On the State of Our World

First, George Weigel prefaces the Q&A by reminding us of the world we live in. I think that his analysis of the world’s loss of a meta-narrative to be spot on:

What the Pope sees, and what he discusses with frankness, clarity, and compassion… is a world that has lost its story: a world in which the progress promised by the humanisms of the past three centuries is now gravely threatened by understandings of the human person that reduce our humanity to a congeries of cosmic chemical accidents: a humanity with not intentional origin, no noble destiny, and thus no path to take through history.

Truth, Judgment, and Love

Once the Q&A begins, there are plenty of noteworthy quotes from the pope. One of the key themes of this book is the need to hold together the idea of love and judgment. Recent scandals have forced this issue upon Catholics, but wee as evangelicals need to hear this truth just as badly, particularly in regards to church discipline:

The prevailing mentality was the the Church must not be a Church of laws but, rather, a Church of love; she must not punish. Thus the awareness that punishment can be an act of love ceased to exist. This led to an odd darkening of the mind, even in very good people…

Ultimately this also narrowed the concept of love, which in fact is not just being nice or courteous, but is found in the truth. And another component of truth is that I must punish the one who has sinned against real love.

Conversion and Christianity

There are places where the Pope sounds like an evangelical, especially in his talk about mercy and grace. Take his answer to the question about his prayer life:

As far as the Pope is concerned, he too is a simple beggar before God – even more than all other people.

Or this admission that revival takes place from conversion, not institutional changes:

Spontaneous new beginnings arise, not from institutions, but out of an authentic faith.

When it comes to conversion, Benedict sounds a lot like John Piper on desiring joy and Tim Keller on idolatry:

Man strives for eternal joy; he would like pleasure in the extreme, would like what is eternal. But when there is no God, it is not granted to him and it cannot be. Then he himself must now create something that is fictitious, a false eternity. We have to show – and also live this accordingly – that the eternity man needs can come only from God.

But there are times when his emphasis on personal transformation by God’s grace is muddled with moralism. At one point, he rightfully insists that Christianity is not a moralistic system of rules:

The Church is not here to place burdens on the shoulders of mankind, and she does not offer some sort of moral system. The really crucial thing is that the Church offers Him.

Yet, just a few pages later, Benedict points to Christ as helper in our striving for morality rather than Savior:

Man can be saved only when moral energies gather strength in his heart; energies that come only from the encounter with God; energies of resistance. We therefore need him, the Other, who helps us be what we ourselves cannot be; and we need Christ, who gathers us into a communion that we call the Church.

Christianity and the World

When it comes to society, Benedict’s analysis is very helpful. He recognizes the inability of politics to produce lasting change. There is a need for people to act according to higher principles, not just within the confines of the law:

Statistics do not suffice as a criterion for morality. It is bad enough when public opinion polls become the criterion of political decisions and when politicians are more preoccupied with “How do I get more votes?” than “What is right?”

How can the great moral will, which everybody affirms and everyone invokes, become a personal decision? For unless that happens, politics remains impotent.

He also sees through society’s call to “tolerance” as masking an intolerant absolutism:

When, for example, in the name of non-discrimination, people try to force the Catholic Church to change her position on homosexuality or the ordination of women, then that means that she is no longer allowed to live out her own identity and that, instead, an abstract, negative religion is being made into a tyrannical standard that everyone must follow.

In the name of tolerance, tolerance is being abolished. This is a real threat we face.

Christianity finds itself exposed now to an intolerant pressure that at first ridicules it – as belonging to a perverse, false way of thinking – and then tries to deprive it of breathing space in the name of an ostensible rationality.

On Core Convictions and Changeable Expressions

When it comes to compromising core convictions, Benedict is both open and closed. In some areas, he maintains that Christian conviction will not allow us to shift with the tides:

The Church has “no authority” to ordain women. The point is not that we are saying that we don’t want to, but that we can’t.

Following (Christ) is an act of obedience. This obedience may be arduous in today’s situation. But it is important precisely for the Church to show that we are not a regime based on arbitrary rule. We cannot do what we want. Rather, the Lord has a will for us, a will to which we adhere, even though doing so is arduous and difficult in this culture and civilization.

Yet there are areas in which we can (and must) change with the times. Notice Benedict’s version of “theological triage”:

We always need to ask what are the things that may once have been considered essential to Christianity but in reality were only the expression of a certain period. What, then, is really essential? This means that we must constantly return to the gospel and the teachings of the faith in order to see:

- First, what is an essential component?

- Second, what legitimately changes with the changing times?

- And third, what is not an essential component? In the end, then, the decisive point is always to achieve the proper discernment.

The Dignity of Humanity

Regarding ethical issues, Benedict reminds us of the dignity of being human:

Being human is something great, a great challenge, to which the banality of just drifting along doesn’t do justice. There needs to be a new sense that being human is subject to a higher set of standards, indeed, that it is precisely these demands that make a greater happiness possible in the first place.

This understanding of human dignity provides the backdrop for his vision of sexuality:

The sheer fixation on the condom implies a banalization of sexuality, which, after all, is precisely the dangerous source of the attitude of no longer seeing sexuality as the expression of love, but only a sort of drug that people administer to themselves.

If we separate sexuality and fecundity from each other in principle, which is what use of the pill does, then sexuality becomes arbitrary. Logically, every form of sexuality is of equal value.

The dignity of human beings is also the reason why science alone cannot provide us with the answers we long for:

Science alone, in its self-isolating search for autonomy, does not do justice to the whole range of our life. It is a sector that gives us great gifts, but it depends in turn on man’s remaining man.

Concluding Thoughts

Despite all the good in Pope Benedict’s book, there are the flaws one would expect from a Roman Catholic (too high an emphasis on Mary, a view of evangelical churches as “defective cells”, hyper-sacramentalism, etc.).

But evangelicals will find much food for thought in this unprecedented “Q&A” with the Pope. When asked what Jesus wants from us, Benedict replies:

He wants us to believe him. To let ourselves be led by him. To live with him. And so to become more and more like him and thus, to live rightly.