Racial unity is a gospel issue and all the more urgent 50 years after the events of 1968. Join the The Gospel Coalition and Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission at a special event, “MLK50: Gospel Reflections from the Mountaintop,” taking place April 3-4 in Memphis. Key speakers include John Perkins, Russell Moore, Benjamin Watson, Ralph West, John Piper, Jackie Hill Perry, Matt Chandler, Eric Mason, and many others. Learn more here.

At 87 years old, John Perkins is ready for his eighth career.

After being a janitor, welder, equipment designer, Bible teacher, civil-rights activist, community developer, and author, Perkins wants to “devote the rest of my life to biblical reconciliation.”

It would be hard to find someone better qualified.

Perkins grew up in a sharecropping family on a Southern plantation, with an absentee father and a mother who died of malnutrition when he was seven months old. He remembers the sting of a white boy’s BB gun (and the frustration of knowing he couldn’t fight back), going around to the main house’s back door, and watching old black men step off the sidewalk to let white women pass by.

Things didn’t get better. Perkins spent most of his adult life working in under-resourced black communities, held down by white segregation and oppression. His older brother, freshly back from serving in World War II, was killed by a white police officer. And Perkins himself was jailed and tortured by racist white police in 1970.

But while Perkins spent the next 50 years fighting back—he led demonstrations and filed lawsuits on behalf of blacks on issues of equal pay, hiring practices, poor treatment of inmates, and voting rights—he also championed forgiveness and reconciliation.

“What I admire about Dr. Perkins is that he wouldn’t hold his tongue about justice, but he is also critical of people doing justice not grounded in the saving knowledge of Jesus Christ,” pastor CJ Rhodes said. “He is able to hold together a profound justice critique with a biblical worldview.”

That makes his message a powerful one for both white and black church leaders.

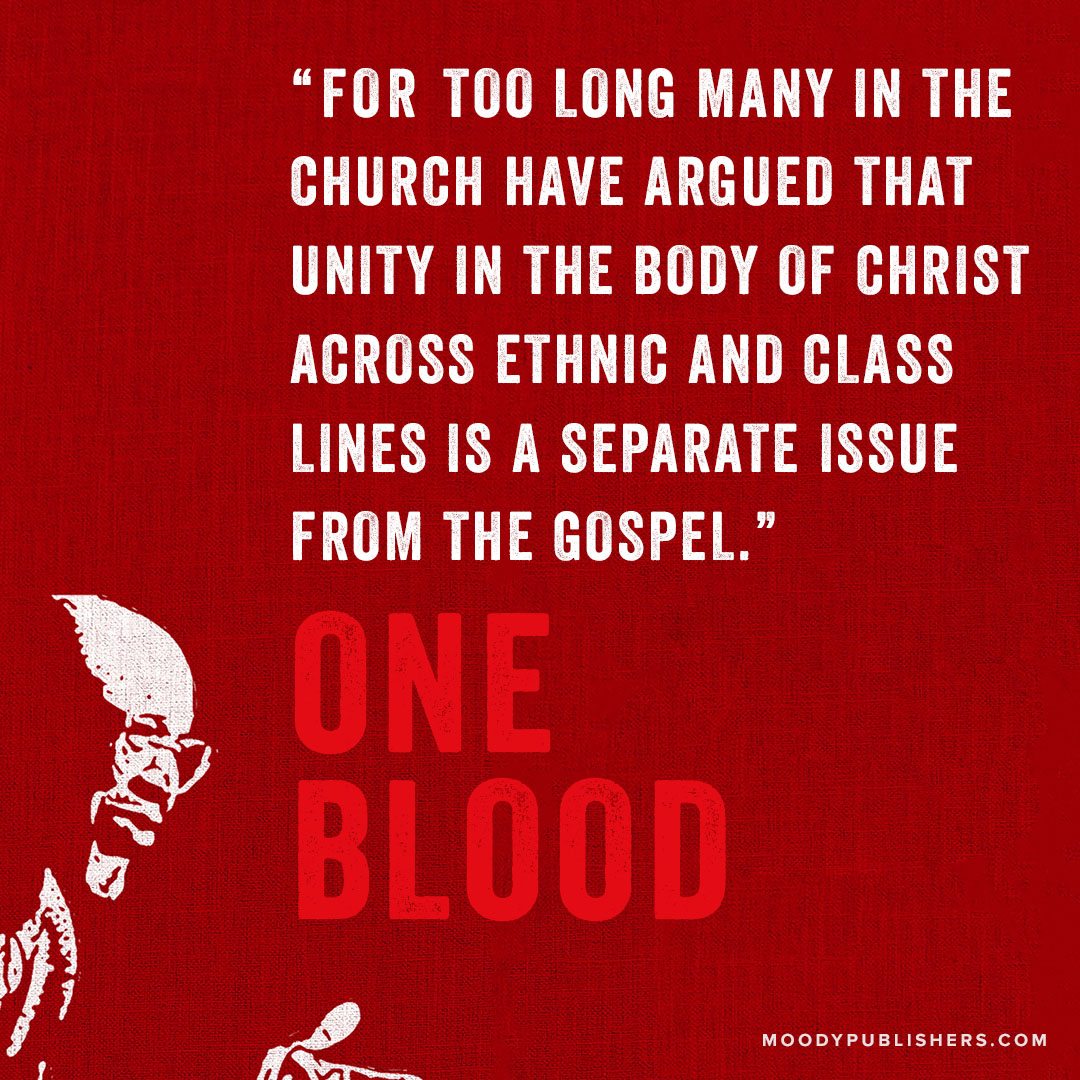

“This is a God-sized problem,” Perkins wrote in One Blood: Parting Words to the Church on Race. The book—Perkins’s “final manifesto”—is due out tomorrow. “It is one that only the church, through the power of the Holy Spirit, can heal. It requires the quality of love that only our Savior can provide.”

Love—as defined by 1 John 3—is Perkins’s legacy, said Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission president and TGC Council member Russell Moore. “It’s a love for God and one another that is not merely verbal or emotional, but an active, working, reconciling love.”

Saved

Along with sharecropping, “my folks back in Mississippi as a boy were bootleggers and gamblers—we were not religious people,” Perkins told TGC. “I didn’t believe in God. I saw the church as just another entity in the world.”

In fact, he could not understand “why black folk were Baptist because all the white folk were Baptist,” he told Charles Marsh in a 2009 interview. “So early on, I sort of felt about the church . . . it was sort of written off.”

His antipathy toward white men flared hotter when his older brother Clyde, safely home from World War II, was shot and killed by a town marshal. His crime? Blocking the marshal’s club from hitting him a second time. The behavior that warranted a clubbing? Talking too loud.

Perkins was furious; to keep him safe, his family sent him west to California. There, his son Spencer began attending a Bible class at a local church. Eventually, he took Perkins along.

“In that Sunday school, I finally met Jesus,” Perkins wrote in One Blood. “Almost immediately God began to do something radical in my heart. He began to challenge my prejudices and my hatred toward others. I had learned to hate the white people in Mississippi. . . . And if I had not met Jesus, I would have died carrying that heavy burden of hate to my grave. But he began to strip it away, layer by layer.”

He went back to Mississippi, thinking “the gospel could burn through those racial barriers,” he told Marsh. “Then I faced the harsh reality.”

In 1962, he founded the Voice of Calvary, the umbrella ministry under which he tucked a day-care center, an adult-education center, a thrift store, a health center, and more.

That same year two people were killed and hundreds injured in riots over James Meredith’s admission to the University of Mississippi. The next year, three black students sparked a riot by sitting at the “Whites Only” counter at Woolworth’s in Jackson. A year later, three Freedom Summer workers were famously killed and their bodies hidden by Ku Klux Klansmen.

I had learned to hate the white people in Mississippi. . . . And if I had not met Jesus, I would have died carrying that heavy burden of hate to my grave.

Early in 1970, Perkins headed to the Rankin County Jail in Brandon, Mississippi, to post bail for some of his arrested civil-rights demonstrators. Before he could even get into the building, highway patrol officers met him with their fists.

Perkins survived the night, but five months later, the stress prompted a heart attack and then ulcers. He spent long hours recuperating in a hospital.

“I had a lot of time to think,” he told Billy Graham Center interviewer Paul Ericksen.

“I thought with real sadness of the gospel I believed in with all my heart,” he wrote of that time in his 1976 autobiography, Let Justice Roll Down. “I believed that gospel was powerful enough to shatter even the hatred of [my hometown of] Mendenhall. But I had not seen it. Especially in the churches.”

After thinking for a while, though, he could see flickers of hope. Perkins’s doctor was white. One of his attorneys was white. White people supported Voice of Calvary with their money and their time. Two white people had even been arrested and beaten alongside him.

“God used the black and white nurses and doctors at that hospital to wash my wounds,” he wrote in One Blood. “For me they were symbolic of the people who had beaten me. What they did healed more than just my broken body. It healed my heart. . . . Oh, how beautiful it would be if we could wash one another’s wounds from the evil of racism in the church!”

Racism in the Church

“John modeled that kind of forgiveness and willingness to deal with white evangelicals in a very wonderful way,” theologian and social activist Ron Sider said. He’s known Perkins since early 1973, when both were at the event that produced the Chicago Declaration of Evangelical Social Concern. “He has played an enormous role in helping white evangelicals make a little bit of progress on racism.”

Seattle Pacific University opened the John Perkins Center in 2004 to research and address structural disparities. In 2013, Calvin College started the John M. Perkins Leadership Fellows to help students address poverty, injustice, and racism. In 2009, Switchfoot wrote a song about his love for both the oppressed and oppressor.

Over the past 20 years, the Southern Baptist Convention has apologized to African Americans for racism, repudiated the Confederate battle flag, and condemned alt-right white supremacy. The Presbyterian Church in America voted to repent of its history of barring blacks from membership, defending white supremacists, and teaching that the Bible sanctioned segregation.

Perkins loves denominational apologies (“I love it. I’d love it if they’d do it again.”), but the resolutions don’t mean that those denominations are now empty of racism.

“There have been a number of local therapeutic reconciliation moments where we feel good in the moment—it’s cathartic, we weep, we hug each other, we go golfing together,” said Rhodes (whose work on reconciliation in the church “only makes sense in the larger scope of the work that people like Dr. Perkins have done. I’m a successor of that.”)

But that reconciliation alone can be shallow, he said. It can lead to the “moderate gradualist perspective”; in other words, white pastors saying of racial injustice, “Hey, let it work itself out.”

That’s something white pastors have been saying for decades, Moore said.

“Many times white people assume that time alone will eradicate these problems,” he said. “So that one can say, ‘It’s 2018, not 1968.’ But time won’t do that. . . . In many ways, we’re facing some of the exact same problems the church was faced with in the 1960s, and with some of the exact same manifestations of the same arguments.”

One of them is “let’s just focus on the gospel” to the exclusion of racial reconciliation, he said. “That’s exactly what white evangelicals were saying in Birmingham that prompted [Martin Luther King’s] ‘Letter from the Birmingham Jail.’”

A newer struggle is lopsided integration, where bright young black leaders are invited to leadership positions in white churches seeking to become multiethnic. To black churches, that can sometimes feel like a raid, Rhodes said.

Better options might be planting a black pastor in a black neighborhood or committing resources to struggling black churches, Rhodes said.

No matter how it’s done—black people coming to white churches, or white people coming to black churches, or black and white people starting new churches together—Perkins’s dream is for them to come together.

“I’m just now seeing clearly that the black church can’t fix this,” Perkins wrote in One Blood. “And the white church can’t fix this. It must be the reconciled Church, black and white Christians together imagining Christ to the world.”

Next Generation

Perhaps the easiest route to racial integration is through the younger generations. Millennials have generally been found to be more racially accepting than their parents or grandparents, probably because they’re America’s most diverse generation yet. Census data shows more than 40 percent identify as non-white.

“Millennials aren’t looking to go to a conference to have racial reconciliation,” said Vincent Joplin, Perkins’s “spiritual grandson.” He works in Memphis, both as a pastor and elder at a majority-white church and as a church planter in a majority-black community.

The younger generation already “shares the same music, the same clothes, the same ideas,” he said. They don’t need to be taught racial harmony in the same way—they’re dating each other, listening to the same music, sharing the same things on social media.

But while they’re better connected to one another, they’re less connected to the church, Joplin said. And without that connection, their racial reconciliation stays shallow.

“Our job with them is to teach them not just to do life with each other, but to have the love of Christ,” he said. “Let’s get past working together and partying together and playing on athletic teams together, and let’s confront sin together. Let’s grow in faith together.”

For this generation, John Perkins’s message of forgiveness is just as crucial as it’s ever been.

Ending Well

Perkins has lived long and hard enough “to have seen every manifestation of hate,” Moore said. “He isn’t surprised by it. He isn’t intimidated by it. Nor does he allow it to embitter him.

“Whenever I—in frustration—bring up the continuing racism we have to deal with, John Perkins’s reaction is almost always, ‘Yes, and . . .’—and then he returns to the power of the gospel.”

It’s a gospel that’s leading Perkins, after nearly nine decades of working on civil rights and equal education and access to health care, to spend his last years on biblical reconciliation.

“The Bible says God made all people from one blood,” Perkins wrote in One Blood. “This tells me that he intended that humankind would be a people that were spiritually connected despite their cosmetic variations.”

So that’s what he’s aiming for, carefully choosing places to speak and classes to teach. (One of them is TGC and ERLC’s MLK50 conference—an event largely inspired by Perkins’s life—in Memphis this week.)

“I’m trying to finish with some sense of accountability to God and the people around me,” Perkins told TGC. “I’m trying to walk the Christian life, a life of confession.”

“Almost every time I talk about John Perkins to people, I say, ‘If I have a tenth of his energy when I’m in my 80s, I’d be glad,’” Moore said. “But the more I think about it—if I had a tenth of his godliness at any point in my life, I’d be grateful to God for that.”

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.