Earlier this week, the South Carolina legislature passed and Gov. Nikki Haley signed into law a measure to remove the Confederate battle flag from the state Capitol grounds. The decades-long controversy over the flag was reignited last month when the killer of nine members of a historically black church in Charleston was found to have posed with the flag. “That sort of symbolism is out of step with the justice of Jesus Christ,” wrote TGC Council member Russell Moore. “The cross and the Confederate flag cannot co-exist without one setting the other on fire.”

Here are nine things you should know about the flag, its history, and the controversy:

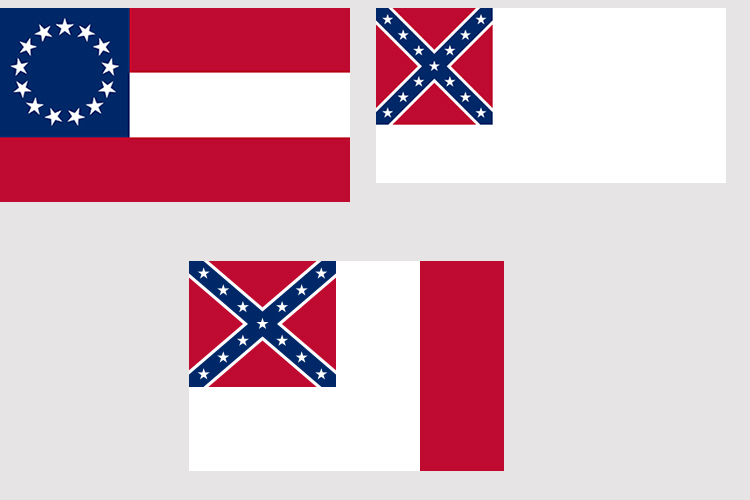

1. What is often called the “Confederate flag” was never the official flag of the Confederate States of America (CSA). It was also not called the “Stars and Bars”—that was the name of the first national flag of the CSA. The flag is properly known as “the battle flag of the Virginia army,” though it was sometimes called “Beauregard’s flag” or “the Virginia battle flag.” Today, it is most commonly called the “Battle Flag.”

2. During its four-year existence from 1861 to 1865, the Confederate States of America had three successive national flags, all created by different designers. William Porcher Miles, the chairman of the Confederate Congress’s “Committee on the Flag and Seal,” designed and submitted what was later known as the “Battle Flag.” His design was rejected in favor of the “Stars and Bars” design that more resembled the American flag. However, the last two flags of the Confederacy did incorporate his design.

3. Miles’s original flag design had an upright cross but he changed it after Charles Moise, a self-described “southerner of Jewish persuasion” objected that the symbol of a particular religion (i.e., Christianity) should not be made the symbol of the nation. Miles later explained the diagonal cross was preferable because it “avoided the religious objection about the cross (from Jews & many Protestant sects)…” Miles also claimed the diagonal cross was “more Heraldic than Ecclesiastical…” [All emphasis in original.]

4. During the early parts of the Civil War, both sides would carry their national emblems into battle. At the first battle of Manassas (Bull Run), the similarity between the USA’s “Stars and Stripes” and the CSA’s “Stars and Bars” caused considerable confusion and even led some Confederate troops to fire on their own units. General P. G. T. Beauregard resolved to adopt a “battle flag” for his command, the army of Virginia. To assist in this project, Beauregard turned to his former aide, William Porcher Miles. Miles submitted his previous design for a national flag, which was officially adopted by Beauregard’s army. Beauregard would later push to have the flag be the standard battle emblem for all CSA units.

5. The second official flag of the CSA, and the first to incorporate the Battle Flag into its design, was the “The Stainless Banner.” This flag was created by William Tappan Thompson, the founder of a Savannah, Georgia newspaper. In a series of editorials, Thompson explained the purpose and meaning of his design:

As a people, we are fighting to maintain the heaven ordained supremacy of the white man over the inferior or colored race; a white flag would thus be emblematical of our cause.

[…]

While we consider the flag which has been adopted by the senate as a very decided improvement of the old United States flag, we still think the battle flag on a pure white field would be more appropriate and handsome. Such a flag would be a suitable emblem of our young confederacy, and sustained by the brave hearts and strong arms of the south, it would soon take rank among the proudest ensigns of the nations, and be hailed by the civilized world as THE WHITE MAN’S FLAG. [emphasis in original]

6. During World War II, displays of the Battle Flag became popular among military troops and units that hailed from Southern states. The Navy cruiser USS Columbia flew the battle flag throughout combat in the South Pacific in honor of the ship’s namesake, the capital city of South Carolina. And after the Battle of Okinawa a Confederate flag was raised over Shuri Castle by a Marine captain from South Carolina.

7. In the mid-20th century, the Battle Flag was again adopted as a symbol by several segregationist and white supremacists groups, including the State’s Rights Democratic Party. This group—popularly called Dixiecrats because they were comprised of Democrats from Dixie (the South)—incorporated the flag in their (only) national convention in 1948. As The Birmingham News reported on July 17, 1948:

The entire audience stood silently with hats over hearts at 10:18 a.m. when a delegation of University of Mississippi students marched to their seats behind the Confederate battle flag.

It was the most impressive and best organized stunt of the convention until that hour and gave the anxious crowd a “break” in their wait for the delayed opening of the conclave.

They were followed into the hall seven minutes later by 10 Birmingham-Southern College students wearing string bow ties and carrying both Confederate battle and Alabama state flags.

8. South Carolina’s first modern hoisting of the Battle Flag came on April 11, 1961, as part of official commemorations of the centennial anniversary of the beginning of the Civil War at Fort Sumter. “The flag is being flown this week at the request of Aiken Rep. John A. May,” reported The State on April 12. During the next legislative session, May introduce a resolution to fly the flag from the capital for a year. By the time that resolution passed on March 16, 1962, the flag had already been flying for nearly a year. The flag remained there as a protest against the civil rights movement of the 1960s, and was later moved to the Statehouse grounds in 2000.

9. The flags of several states (Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi) all have or had elements that were inspired by the Battle Flag or other CSA flags. However, Mississippi’s state flag remains the only one in the U.S. that still features the battle flag prominently in its design. (The flags of Maryland and Virginia were also influenced by the confederacy, though their designs are not based on the flags.)

Other articles in this series:

Elisabeth Elliot • Animal Fighting • Mental Health • Prayer in the Bible • Same-sex Marriage • Genocide • Church Architecture • Auschwitz and Nazi Extermination Camps • Boko Haram • Adoption • Military Chaplains • Atheism • Intimate Partner Violence • Rabbinic Judaism • Hamas • Male Body Image Issues • Mormonism • Islam • Independence Day and the Declaration of Independence • Anglicanism • Transgenderism • Southern Baptist Convention • Surrogacy • John Calvin • The Rwandan Genocide • The Chronicles of Narnia • The Story of Noah • Fred Phelps and Westboro Baptist Church • Pimps and Sex Traffickers • Marriage in America • Black History Month • The Holocaust • Roe v. Wade • Poverty in America • Christmas • The Hobbit • Council of Trent • C.S. Lewis • Orphans • Halloween and Reformation Day • World Hunger • Casinos and Gambling • Prison Rape • 6th Street Baptist Church Bombing • 9/11 Attack Aftermath • Chemical Weapons • March on Washington • Duck Dynasty • Child Brides • Human Trafficking • Scopes Monkey Trial • Social Media • Supreme Court’s Same-Sex Marriage Cases • The Bible • Human Cloning • Pornography and the Brain • Planned Parenthood • Boston Marathon Bombing • Female Body Image Issues

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.