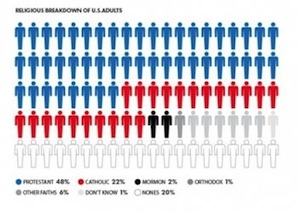

Protestants have lost their majority status in the United States, and the number of Americans with no religious affiliation is rising. Those are the two big conclusions of a recently released study of the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life in America.

For the first time in American history, the United States does not have a Protestant majority. The adult Protestant population reached a new low of 48 percent. That’s down from the 1960s when two in three Americans identified themselves as Protestants. The report records declines in both mainline and evangelical numbers, and that many of these people have joined the ranks of “the Nones,” those who say they have no religion (now one in five Americans).

For the first time in American history, the United States does not have a Protestant majority. The adult Protestant population reached a new low of 48 percent. That’s down from the 1960s when two in three Americans identified themselves as Protestants. The report records declines in both mainline and evangelical numbers, and that many of these people have joined the ranks of “the Nones,” those who say they have no religion (now one in five Americans).

Reading deeper into the study, I wondered about two things. The study counted among the “Nones” those who say they believe in God, pray, and are spiritual but are not religious. I wonder if the study recognized that many evangelical Christians define themselves in this way—-we often say (rather simplistically) “our church is not about religion, but about a relationship with God in Christ.” I also questioned when the study said the number of Protestants has decreased in part due to the growth of non-denominational churches. I know many non-denominational groups that consider themselves Protestant. And I know many non-denominational groups that do not emphasize being Protestant but still act and believe in Protestant ways. But I also know many non-denominational Christians who really aren’t Protestant at all, which makes counting this demographic difficult.

Even so, I do not doubt the broad trend that the Pew study has identified. In fact, the reality may be worse than what the Pew study suggests. In his recent book Bad Religion: How We Became a Nation of Heretics, New York Times columnist Ross Douthat writes about the slow-motion collapse of traditional Christianity in America. He argues that Christian orthodoxy is losing ground to the many ascendant heresies of our day—-new Gnosticism, prosperity gospel, new sects, spiritual narcissism, nationalism, and so on.

Why this trend? The Pew report only touches on a few of the reasons—-but all kinds of causes have been suggested: a move away from the gospel, failure of Christians to live out their faith, identifying Christianity too closely with politics, suffocating materialism, the pluralism of our global age, a spiritual but post-Christian worldview pumped to the young through countless new media portals.

This trend does not quite fit the old secularization thesis—-that societies become less religious the more modern they become. Spirituality and religious pluralism in America are on the rise. Nor does this trend say anything about the overall decline of Christianity. Because while Christianity is declining in the West, it is growing in the Global South and East.

Cause for Reflection

Nevertheless, American Christian leaders need to reflect long and hard about the trend that Pew is reporting. Here are a few quick observations.

(1) This is another reminder denominationalism is in decline.

Identification with a Protestant label such as Presbyterian or Baptist is no longer valued by many, and in some cases it is seen as a hindrance to Christian witness. That said, I am part of a denomination and think healthy denominations are still quite useful. But I realize that the trend is going in the other direction.

(2) Protestants (even evangelicals) have done a poor job of imprinting our identity on our children.

We have either focused on spiritual vibrancy without catechizing, or catechized without emphasizing spiritual vibrancy. Either way, we have lost ground with our youth. Church leaders need to think doubly hard about how we are going to reach and train up the next generation of Christians. We have to rethink the way we do children’s and youth ministry.

(3) There are three wrong responses to this Protestant decline.

One is to batten down the hatches and adopt a fortress mentality when it comes to our culture. Another is to emphasize a lowest common denominator Christianity that insists on as little as possible of Christian truth in order to connect with secular audiences. Still another is to redefine central tenets of the Christian faith and so accommodate the faith to the late modern world.

(4) We need to affirm a robust orthodox Christianity.

In contrast to these approaches, I believe we need to affirm a robust orthodox Christianity, even a confessional Christianity, that keeps Christ and the gospel central to everything we do and say. It should be confessional, but center focused; it should be gracious and not doctrinally belligerent on peripheral concerns.

(5) We need to re-examine how we define Christian discipleship in a culture coming apart.

The early Christians might help us here. They were known for their distinct way of life. They could tell others that following Jesus is a better way to live. Perhaps that is why they were called people of “the way.” The whole era of the early church is more and more relevant to our new cultural setting. They had the challenge of living for Christ in a pluralistic, pagan, pre-Christian environment. We have the challenge of living for Christ in a pluralistic, neo-pagan, post Christian environment. We can learn a lot from the early church.

(6) Some of us are used to thinking of America in Jerusalem or New Jerusalem-like categories.

Without being postmillennial about it, we grew up with the “city on the hill” image. Yet as our culture changes, some aspects of our society are starting to look a lot more like Babylon than Jerusalem. We are looking more like a mission field than a mission-sending center. In terms of evangelism, we can no longer assume that everyone around us is a theist who can draw on long-forgotten Sunday school lessons. More and more people have no church background at all. All of this means that we really do need to live and think like missionaries as our neighborhoods are populated with Muslims, Mormons, spiritualists, and Nones.

The Pew study is another cultural indicator. Take note of it. Talk about it with other Christian leaders. And get ready for the wonderful yet incredible challenge ahead of us—-to be truly Christian in this new environment.

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.